“China is a big country and you are small countries, and that is a fact.” — Chinese foreign minister Yang Jiechi, speaking to ASEAN in 2010

One of the first indicators that Xi Jinping wasn’t as competent a ruler as he was often made out to be was the failure of the Belt and Road megaproject. Belt and Road was one of Xi’s earliest signature initiatives, unveiled in 2013. The idea, as stated, was to have the Chinese government invest in infrastructure projects throughout the world, giving a boost to those countries’ economies while increasing China’s trade opportunities — a massive win-win. There was also the unspoken idea that this lavish outlay would win China geopolitical friends and allies around the world while also enhancing its access to critical natural resources and potentially even military basing sites. According to the Council on Foreign Relations and many other sources, China has already spent $1 trillion on the Belt and Road.

Except the way this actually worked is fairly far from our common-sense definitions of “invest” and “spend”. The word “invest” implies that China was paying for infrastructure in these countries that it would then partially own. And the word “spend” implies that this would actually cost China money in the long run — to be made back, hopefully, from the revenues generated by the successful infrastructure projects. This sort of investment would align the incentives of China and the recipient countries — a true win-win.

Except that this is generally not how Belt and Road actually worked. Instead, what China would typically do is loan countries money to build infrastructure projects. China’s government would then help plan those projects. Then the borrowing country would use the money it borrowed from China to build the infrastructure, often paying Chinese contractors to do the actual work.

From China’s perspective, even setting aside the security and diplomatic benefits, this looks like a pretty great deal — at least in the short term. Your contractors get to book massive amounts of revenue, and then your government gets its money back when the recipient country pays back the loan. And the loan is typically collateralized by the infrastructure being built, so if the recipient country doesn’t pay you back, at least you now own a piece of infrastructure in a foreign country, and your contractors got some pork.

From the receiving country’s benefit, it’s a lot riskier. If the infrastructure project doesn’t raise enough money to pay back the loans, the government will have to pay China back using tax money; that will be painful for its citizens. If it can’t do that, it has to surrender the collateral — i.e. the infrastructure — and endure a painful default that will impair its ability to borrow internationally and will cause a deep recession or even a crisis. So the Belt and Road countries made a big bet that China would design them some really good infrastructure projects.

By and large, China did not do that. Many of the projects were poorly planned and executed. In Myanmar, Chinese planners seemed to assume that they could just boot peasants off their land to build some pipelines as would be standard practice in China; instead, they sparked massive protests. In Pakistan, angry locals simply attacked the Chinese workers.

Meanwhile, in Sri Lanka, China built out a whole port at Hambantota that was supposed to supercharge Sri Lanka’s trade. It turned out that no one really needed another big Sri Lankan port; everyone just kept trading at the capital city of Colombo, which had recently improved its port infrastructure. In China, infrastructure projects don’t always have to make money; the economic activity generated by construction is often a higher priority for the government than making a financial return. But for Belt and Road borrowers, the stakes are much higher. Hambantota became a massive white elephant, which couldn’t generate anywhere near enough cash to pay back the loans that Sri Lanka took from China to build it. Sri Lanka is also pretty bad at raising tax revenue. So it defaulted, and China got control of the port.

And in addition to bad planning, China often delivers poor execution. This is from a WSJ report in January:

[I]t was the biggest infrastructure project ever in [Ecuador], a concrete colossus bankrolled by Chinese cash…Today, thousands of cracks have emerged in the $2.7 billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant, government engineers said, raising concerns that Ecuador’s biggest source of power could break down. At the same time, the Coca River’s mountainous slopes are eroding…

[L]ow-quality construction on some of the [Belt and Road] projects risks crippling key infrastructure and saddling nations with even more costs…In Pakistan, officials shut down the Neelum-Jhelum hydroelectric plant last year after detecting cracks in a tunnel…The closure of the plant has already cost Pakistan about $44 million a month…Uganda’s power generation company said it has identified more than 500 construction defects in a Chinese-built 183-megawatt hydropower plant on the Nile river that has suffered frequent breakdowns…Completion of another Chinese-built hydropower plant further down the Nile…is three years behind schedule, a delay that Ugandan officials have blamed on various construction defects, including cracked walls…In Angola [at] a vast social housing project outside the capital of Luanda, many locals are complaining about cracked walls, moldy ceilings and poor construction.

Even Indonesia’s high-speed rail line in Jakarta, sometimes touted as the most successful Belt and Road project, had massive cost overruns and fell years behind schedule. (It also is only 88 miles long.)

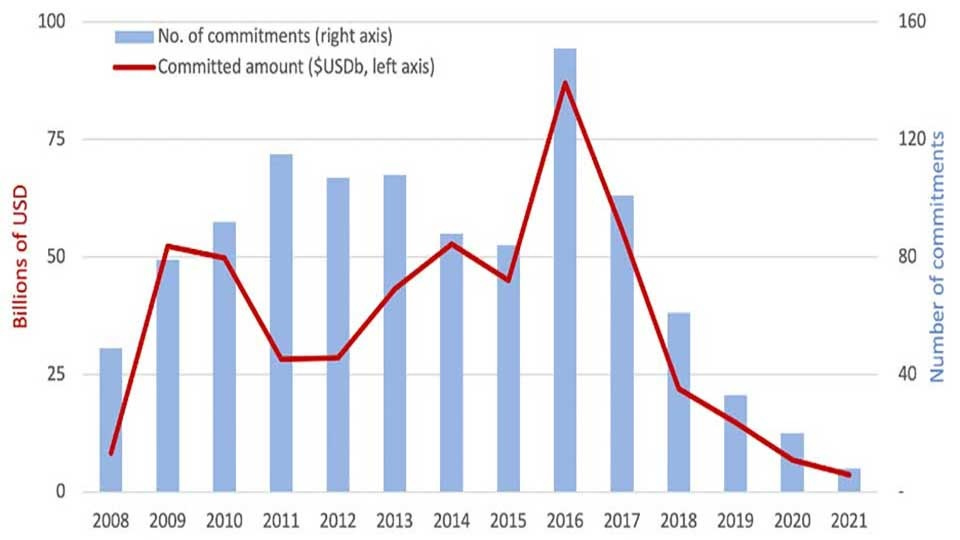

At some point, China’s government realized that the Belt and Road projects were failing and that it was going to have to choose between losing a lot of money and making a lot of other countries very angry. As a result, Belt and Road lending collapsed even before the pandemic hit:

Increasingly, the Belt and Road is more notional than real, a way for China to declare that it’s the leader of the Global South — kind of like BRICS.

But in the meantime, the borrowing countries are still saddled with a whole lot of debt. China has forgiven some of it, but sometimes it’s choosing to be intransigent. In Sri Lanka, which is in the middle of a severe economic crisis, China is refusing to cooperate with other international lenders on a rescue package. The Economist reports:

The IMF cannot lend more unless Sri Lanka restructures its debts, since the country owes so much elsewhere that officials cannot otherwise be sure they will get their money back. Therefore by refusing to take a haircut on its debts, China is holding up Sri Lanka’s restructuring—as it is in other indebted countries, too.

And remember, this is after Sri Lanka basically gave Hambantota’s port to China.

Nor is Sri Lanka the only one feeling the pain of Belt and Road mistakes. Here’s an AP story from May:

An Associated Press analysis of a dozen countries most indebted to China — including Pakistan, Kenya, Zambia, Laos and Mongolia — found paying back that debt is consuming an ever-greater amount of the tax revenue needed to keep schools open, provide electricity and pay for food and fuel…

Behind the scenes is China’s reluctance to forgive debt and its extreme secrecy about how much money it has loaned and on what terms, which has kept other major lenders from stepping in to help. On top of that is the recent discovery that borrowers have been required to put cash in hidden escrow accounts that push China to the front of the line of creditors to be paid…

Countries in AP’s analysis had as much as 50% of their foreign loans from China and most were devoting more than a third of government revenue to paying off foreign debt.

Now, there actually are some things that the IMF and other lenders can do to help countries like Sri Lanka. Jennifer Harris points out that the IMF can lend into “official arrears”, which would allow Sri Lanka to get a bailout even if it defaults on its China payments. That’s good.

But let’s stop to consider just how crazy this makes the whole economic model of the Belt and Road look. Suppose a rich guy walks up to you and tells you that he first made it in the food truck business, and you can too. He offers to lend you money to buy a food truck and get started earning cash. He’s a rich successful guy, so you believe him, and you take the deal. Oh, and he owns the company that sells you the food truck, and he also owns the company that sells you the ingredients, so you’re just taking the money he lends you and turning right around and giving it to his businesses.

And then it turns out that the food truck business isn’t nearly as great as he led you to believe. Your business folds. But guess what — you still owe money to the rich guy! First, he gets the truck he sold you, since that was collateral for the loan. But you still owe him some more, and he demands payment! You’re broke, you have no money and no truck, and you’re on the hook to this guy who dazzled you with bad advice. And he’s not in a mood to forgive your debt.

On paper, cases like Sri Lanka’s look like a win for China at other countries’ expense — well-connected Chinese contractors got paid out, China got a port in a highly strategic region, and they might still get Sri Lanka to cough up the rest of the money they owe, which will have to be squeezed from suffering Sri Lankan farmers in the form of higher taxes. From China’s perspective, what’s not to like?

But in the long run, this is almost certain to hurt China’s image in the world. Back when the money was flowing, the countries of the Global South saw China in a highly positive light — after all, the West’s money always comes with strings attached.

But because the Belt and Road was so ill-conceived, this warm fuzzy feeling always had an expiration date. Now that the Belt and Road has basically failed, and the cash faucet has been shut off, delight at China’s seeming largesse is clearly going to be replaced with resentment and distrust. Acting like a mafia loanshark is not generally a way to win friends and influence people.

Note that although this is a debt trap, it isn’t really a case of “debt-trap diplomacy”, as some people accuse. Debt-trap diplomacy is where you get a country to owe you money, and you force it to make geopolitical concessions in exchange for loan forbearance. China doesn’t appear to be doing that; instead it appears to simply be walking away with as much of the money as it can, and thumbing its nose as it walks away, and leaving developing countries bitter and resentful.

That’s just a mind-bogglingly bad long-term strategy for achieving global leadership. China’s leaders tout their country as the leader of the Global South, but they’re raiding developing countries like their own personal piggy bank. Throughout the whole saga of the Belt and Road, China’s government treated countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Zambia like Chinese provinces — assuming they could and would strongarm their populations into supporting new infrastructure, prioritizing economic throughput over efficiency and profitability, and counting on those other countries to take the hit when the projects went…er…south.

No comments:

Post a Comment