Quote of the day

“I find economics increasingly satisfactory, and I think I am rather good at it.”– John Maynard Keynes

Tuesday, 31 January 2017

Disruption - a hint of what is to come

Sunday, 29 January 2017

Institutions of the EU at a glance

Wednesday, 25 January 2017

You need to start reading up on global trade

This BBC page is a good place to start - links to all sorts of information relevant to prior development, and what lies ahead

Here's a great collection of articles from the BBC on the hefty topic of Global Trade - it could easily form the basis of an independent reading and research task, with articles on the pros and cons of free trade, the impact of containerisation, trade wars, globalisation, and new trade links via train with China, amongst others - I reckon there's an example for every part of the Global topic. Given that careful reading of the AQA 25m essay "levels of response" table suggests that top band responses demonstrate "application to a given context" and "good use of data", and that evaluation is "well supported", the important of wider reading and knowledge of examples has never been greater.

Labels:

free trade,

global economy,

globalisation,

trade,

trade agreement,

trade barriers,

trade deficit

Tuesday, 24 January 2017

Monday, 23 January 2017

Cracking discussion of manufacturing - essential for A2

Manufacturing is in the spotlight as a way to revitalise economies. The Economist takes a look, and I’ve summarised some of the article.

Donald Trump has promised to create “millions of manufacturing jobs”. George Osborne, Britain’s former finance minister talked of “a Britain carried aloft by the march of the makers”, which continues with the “comprehensive industrial strategy” promised by Theresa May.

What is manufacturing? Assembling parts into cars, washing machines or aircraft adds less value than once it did; design, supply-chain management, aftercare and servicing add much more.

Manufacturing is harder to define than it seems, and to capture in statistics. Does manufacturing have the capability to generate millions more jobs? There are still a lot of them; but many of the good jobs for the less skilled are never to return, according to the authors.

Manufacturers are more likely to be exporters than businesses in other parts of the economy and, as you would expect given the demands of competing in a broader market, exporting firms tend to be more productive than non-exporting firms. They may even be more innovative. Such firms also tend to be more capital-intensive, because selling into those broader markets allows firms to capture economies of scale. And a sector that has higher-than-average productivity and high capital intensity will, other things being equal, be able to offer better wages.

Globalisation driven by container shipping and information technology has allowed firms to unbundle the different tasks—from design to assembly to sales—that made up the business of manufacturing. It became possible to co-ordinate longer and more complicated supply chains, and thus for various activities to be moved to other countries, or to other companies, or both. At the same time computers and computer-aided design made automation more capable. High wages gave owners the incentive they needed to take advantage of those opportunities. As a result many manufacturing jobs vanished from the rich world.

Tens of millions of jobs went, and as manufacturing became more productive, and prices dropped, its share of GDP fell, too. At the same time the number of people in manufacturing in developing countries exploded. I’ve blogged about this in the past, since industrialisation is assumed to be a part of most poor countries’ development model:

Industrialisation in Africa

Can poorer countries follow China's growth model?

Routine work, which is not particularly valuable (it has a low marginal revenue product – MRP) will easily move to poor countries where labour is cheaper. If poor places have the capacity to take the high-value bits, they will no longer be poor.

According to the article, this is why promises to bring jobs back to the rich world aren’t going to happen . High wage semi-skilled manufacturing jobs are not going to return because they were not simply shipped abroad. They were destroyed by new ways of boosting productivity and reducing costs.

Where does manufacturing fit into the economies of rich countries? Astonishingly, by some estimates, putting together Airbus airliners accounts for just 5% of the added value of their manufacture and assembly in China accounted for just 1.6% of the retail cost of early Apple iPads.

Most pre-production value added comes from R&D and the design of both the product and the industrial processes required to make it. More is provided by the expert management of the complex supply chains that provide the components for final assembly. After production, taking products to market and after-sales repair and service and disposal all add more value.

A study published in 2015 reckoned that the 11.5m American jobs counted as manufacturing work in 2010 were outnumbered almost two to one by jobs in manufacturing-related services, bringing the total to 32.9m. A British study in 2016 came to a similar conclusion: that 2.6m production jobs supported another 1m in pre-production activities and 1.3m in post-production jobs.

I’ve learned that the definition of manufacturing is so complex that the term needs to be handled with thought and reflection – which is good when making evaluation statements.

What is manufacturing? Assembling parts into cars, washing machines or aircraft adds less value than once it did; design, supply-chain management, aftercare and servicing add much more.

Manufacturing is harder to define than it seems, and to capture in statistics. Does manufacturing have the capability to generate millions more jobs? There are still a lot of them; but many of the good jobs for the less skilled are never to return, according to the authors.

Manufacturers are more likely to be exporters than businesses in other parts of the economy and, as you would expect given the demands of competing in a broader market, exporting firms tend to be more productive than non-exporting firms. They may even be more innovative. Such firms also tend to be more capital-intensive, because selling into those broader markets allows firms to capture economies of scale. And a sector that has higher-than-average productivity and high capital intensity will, other things being equal, be able to offer better wages.

Globalisation driven by container shipping and information technology has allowed firms to unbundle the different tasks—from design to assembly to sales—that made up the business of manufacturing. It became possible to co-ordinate longer and more complicated supply chains, and thus for various activities to be moved to other countries, or to other companies, or both. At the same time computers and computer-aided design made automation more capable. High wages gave owners the incentive they needed to take advantage of those opportunities. As a result many manufacturing jobs vanished from the rich world.

Tens of millions of jobs went, and as manufacturing became more productive, and prices dropped, its share of GDP fell, too. At the same time the number of people in manufacturing in developing countries exploded. I’ve blogged about this in the past, since industrialisation is assumed to be a part of most poor countries’ development model:

Industrialisation in Africa

Can poorer countries follow China's growth model?

Routine work, which is not particularly valuable (it has a low marginal revenue product – MRP) will easily move to poor countries where labour is cheaper. If poor places have the capacity to take the high-value bits, they will no longer be poor.

According to the article, this is why promises to bring jobs back to the rich world aren’t going to happen . High wage semi-skilled manufacturing jobs are not going to return because they were not simply shipped abroad. They were destroyed by new ways of boosting productivity and reducing costs.

Where does manufacturing fit into the economies of rich countries? Astonishingly, by some estimates, putting together Airbus airliners accounts for just 5% of the added value of their manufacture and assembly in China accounted for just 1.6% of the retail cost of early Apple iPads.

Most pre-production value added comes from R&D and the design of both the product and the industrial processes required to make it. More is provided by the expert management of the complex supply chains that provide the components for final assembly. After production, taking products to market and after-sales repair and service and disposal all add more value.

A study published in 2015 reckoned that the 11.5m American jobs counted as manufacturing work in 2010 were outnumbered almost two to one by jobs in manufacturing-related services, bringing the total to 32.9m. A British study in 2016 came to a similar conclusion: that 2.6m production jobs supported another 1m in pre-production activities and 1.3m in post-production jobs.

I’ve learned that the definition of manufacturing is so complex that the term needs to be handled with thought and reflection – which is good when making evaluation statements.

Labels:

development,

global economy,

jobs,

manufacturing,

R&D

Saturday, 21 January 2017

Natural resources & the UK?

Just so you know about the Cornish lithium

By Tim WorstallComments:27 CommentsCornwall looks set for a £50billion mining revolution after plans were revealed to make Poldark country Europe’s sole producer of lithium.

Lithium – known as ‘white petroleum’ – is used in the rapidly growing market for electric cars and rechargeable batteries in everything from mobile phones to cordless vacuums.

Most lithium is produced in South America, Australia and China but there are vast quantities locked inside its large granite stores up to 1,000 metres below the Cornish soil.But with no European source the UK Government has earmarked lithium as a metal of strategic importance to the country and new mines could be opened or existing ones brought back into action.

I don’t say that this will work and I’m certainly not suggesting that you invest.

However, it is at least realistic .

There’s plenty of lithium around, any number of places you could get it from (there are at least two plans within 10 km of where I am now in Bohemia). But two good starts are with granite and with hot brines. And here in Cornwall they’re talking about extraction from hot brines running through granite – an entirely reasonable starting point.

Myself I would check on one other source before charging ahead though. The wastes from the China clay industry will have a decent amount of lithium in them and God Knows there’s enough of that lying about…..

Micro - train fares; very topical

Two posts, one from 2014 looking at the usual complaints about fare rises, which has some useful arguments about privatisation (both sides of the arfument, don't forget), and another from this year:

Yes there's a problem with train fares - they're too low

Tim Worstall, January 2017

This year, as every year, the New Year has been accompanied by a chorus of whining about how the price of rail tickets has gone up again. The Campaign for Better Transport called the latest rises a “kick in the teeth” for passengers. Railfuture accused the Government of acting like Blue Meanies. Transport Focus called for a price freeze, while Action for Rail insisted that British passengers are paying six times as much as Europeans. All were in agreement that passengers are being asked to pay far too much.

But there’s an argument to make – an overwhelming one, in fact – that train tickets in the UK, and even in the South-East, aren’t too expensive, but too cheap. It’s an argument that has nothing to do with privatisation – in fact, it would still be true if the whole system were nationalised again.

In a recent interview, Paul Plummer of the Rail Delivery Group, which represents train operators and Network Rail, said: “With passenger numbers doubling in the last 20 years, money from fares now almost covers the railway’s day-to-day operating costs.” In other words, the rise in ticket prices in recent is the result of a specific, deliberate and entirely correct policy decision: that those who travel on the iron roads should pay the costs of their own damn choices.

So yes, it is true that rail fares in Britain are higher than in most other places in Europe. It is also true that the costs of running the railways are largely the same across Europe. The difference is that in other countries, the general taxpayer has to subsidise those travellers as they sit nice and warm in their carriages. Here, the passenger pays the cost of being a passenger. Which, of course, is right and proper – you do not pay through your taxes for my shoe leather if I walk to work, my energy expenditure if I cycle, or my petrol if I drive. So why should you pay for me to be in a comfy seat, or crammed into the aisles, as the train takes the strain?

In fact, fares still don’t cover the full cost of the journey – because they only pay for the running costs of the railways, not the capital costs. Which suggests that prices are actually still too low. The rail system should, as any system should, cover its costs from the voluntary payments of those who wish to use it. All that is happening here is that rail users are being confronted with the real costs of their choices, or something approaching them.

And if they were confronted with the full and true expense – for infrastructure as well as operational costs – perhaps they would realise that an integrated transport system isn’t such a cheap option after all. What these annual moans boil down to, in other words, is rail passengers complaining about being told to pay for their chosen form of transport. I’d be sympathetic – if it weren’t for the implicit demand that those of us who don’t use the trains should cough up instead. To which the correct response is that Anglo-Saxon thing with the waving of the two fingers. You pay for yourself, matey.

Willy Hutton on train faresAugust 24, 2014 By Tim Worstall

"This is devastating. British rail fares, the highest per passenger mile of any country in Europe, are set to become higher still. This is a poll tax on wheels, to many, an unavoidable impost that must be paid at the same rate by rich and poor alike, even though rail transport is an indispensable public service."

Err, no, not really. If everyone in the country is taxed so that fares can be subsidised by the Treasury then that’s more like a poll tax. Because no one has any choice about whether they pay for the railways or not. If passengers pay for the trains then not everyone has to pay do they? Those who so organise their lives so that they don’t take trains aren’t paying for the trains, are they?

Conceptually, it was absurd to divide the network from the train companies that run on it; any rail system works as an integrated whole. That’s the European Union that insists upon that. Nowt to do with domestic politics at all: and also something that wouldn’t be changed if there was nationalisation.

It was equally a conceptual disaster to imagine that because each train licence is of necessity a monopoly – you can’t have two services from London to say Manchester competing against each other – the monopoly had to be temporary with renewable licences auctioned at 10-year intervals.

Odd that. There’s at least two different companies competing on one route I know, London to Bath.

What’s more, it was crazed to believe a public good required minimal or no public grants. Trains are a public good now? If they were they’d never have been built, would they? For the point of a public good is that it is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Neither of which apply to a railway. They might well be public services but that’s a very different marmite de poisson.

Lastly, it was asinine not to understand that private capital demands financial returns well above the cost of capital available to the low-risk state. As a result, there have to be never-ending and ongoing efficiency gains beyond the initial round of layoffs and wage cuts to deliver those extra returns. Err, yes, that’s the point.

That cannot be done even by the hand of God. The only recourse is poorer service provision. Trains are worse now then they were? When you also, in the same piece, say this? After all, investment is booming, passenger numbers rising and safety is better. It’s not all bad.

Privatisation has made the service worse? Directly Operated Railways is the 100% publicly owned company that took over the east coast mainline when the incompetent private operator walked away from its obligations in 2009. Five years of public ownership and it is now the best run and most efficient operator, making a net surplus of £16m for the taxpayer. Its reward? To be sold back to a private operator next February. Yes, note that verb there: sold. That means cash coming into the state, doesn’t it?

Networks of key public services such as rail are natural monopolies; Eh? We have competing ways to get to Scotland, to Birmingham, from Bath to London. What sodding monopoly?

It’s time to build and expand the public institutions we have and insist that any private holder of a franchise designed to deliver a public good is constituted as a public benefit company with a charter that sets outs obligations to match the privileges, including paying UK tax. We can discuss that when you learn the meaning of “public good” Willy.

Yes there's a problem with train fares - they're too low

Tim Worstall, January 2017

This year, as every year, the New Year has been accompanied by a chorus of whining about how the price of rail tickets has gone up again. The Campaign for Better Transport called the latest rises a “kick in the teeth” for passengers. Railfuture accused the Government of acting like Blue Meanies. Transport Focus called for a price freeze, while Action for Rail insisted that British passengers are paying six times as much as Europeans. All were in agreement that passengers are being asked to pay far too much.

But there’s an argument to make – an overwhelming one, in fact – that train tickets in the UK, and even in the South-East, aren’t too expensive, but too cheap. It’s an argument that has nothing to do with privatisation – in fact, it would still be true if the whole system were nationalised again.

In a recent interview, Paul Plummer of the Rail Delivery Group, which represents train operators and Network Rail, said: “With passenger numbers doubling in the last 20 years, money from fares now almost covers the railway’s day-to-day operating costs.” In other words, the rise in ticket prices in recent is the result of a specific, deliberate and entirely correct policy decision: that those who travel on the iron roads should pay the costs of their own damn choices.

So yes, it is true that rail fares in Britain are higher than in most other places in Europe. It is also true that the costs of running the railways are largely the same across Europe. The difference is that in other countries, the general taxpayer has to subsidise those travellers as they sit nice and warm in their carriages. Here, the passenger pays the cost of being a passenger. Which, of course, is right and proper – you do not pay through your taxes for my shoe leather if I walk to work, my energy expenditure if I cycle, or my petrol if I drive. So why should you pay for me to be in a comfy seat, or crammed into the aisles, as the train takes the strain?

In fact, fares still don’t cover the full cost of the journey – because they only pay for the running costs of the railways, not the capital costs. Which suggests that prices are actually still too low. The rail system should, as any system should, cover its costs from the voluntary payments of those who wish to use it. All that is happening here is that rail users are being confronted with the real costs of their choices, or something approaching them.

And if they were confronted with the full and true expense – for infrastructure as well as operational costs – perhaps they would realise that an integrated transport system isn’t such a cheap option after all. What these annual moans boil down to, in other words, is rail passengers complaining about being told to pay for their chosen form of transport. I’d be sympathetic – if it weren’t for the implicit demand that those of us who don’t use the trains should cough up instead. To which the correct response is that Anglo-Saxon thing with the waving of the two fingers. You pay for yourself, matey.

Willy Hutton on train faresAugust 24, 2014 By Tim Worstall

"This is devastating. British rail fares, the highest per passenger mile of any country in Europe, are set to become higher still. This is a poll tax on wheels, to many, an unavoidable impost that must be paid at the same rate by rich and poor alike, even though rail transport is an indispensable public service."

Err, no, not really. If everyone in the country is taxed so that fares can be subsidised by the Treasury then that’s more like a poll tax. Because no one has any choice about whether they pay for the railways or not. If passengers pay for the trains then not everyone has to pay do they? Those who so organise their lives so that they don’t take trains aren’t paying for the trains, are they?

Conceptually, it was absurd to divide the network from the train companies that run on it; any rail system works as an integrated whole. That’s the European Union that insists upon that. Nowt to do with domestic politics at all: and also something that wouldn’t be changed if there was nationalisation.

It was equally a conceptual disaster to imagine that because each train licence is of necessity a monopoly – you can’t have two services from London to say Manchester competing against each other – the monopoly had to be temporary with renewable licences auctioned at 10-year intervals.

Odd that. There’s at least two different companies competing on one route I know, London to Bath.

What’s more, it was crazed to believe a public good required minimal or no public grants. Trains are a public good now? If they were they’d never have been built, would they? For the point of a public good is that it is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Neither of which apply to a railway. They might well be public services but that’s a very different marmite de poisson.

Lastly, it was asinine not to understand that private capital demands financial returns well above the cost of capital available to the low-risk state. As a result, there have to be never-ending and ongoing efficiency gains beyond the initial round of layoffs and wage cuts to deliver those extra returns. Err, yes, that’s the point.

That cannot be done even by the hand of God. The only recourse is poorer service provision. Trains are worse now then they were? When you also, in the same piece, say this? After all, investment is booming, passenger numbers rising and safety is better. It’s not all bad.

Privatisation has made the service worse? Directly Operated Railways is the 100% publicly owned company that took over the east coast mainline when the incompetent private operator walked away from its obligations in 2009. Five years of public ownership and it is now the best run and most efficient operator, making a net surplus of £16m for the taxpayer. Its reward? To be sold back to a private operator next February. Yes, note that verb there: sold. That means cash coming into the state, doesn’t it?

Networks of key public services such as rail are natural monopolies; Eh? We have competing ways to get to Scotland, to Birmingham, from Bath to London. What sodding monopoly?

It’s time to build and expand the public institutions we have and insist that any private holder of a franchise designed to deliver a public good is constituted as a public benefit company with a charter that sets outs obligations to match the privileges, including paying UK tax. We can discuss that when you learn the meaning of “public good” Willy.

Labels:

excludable,

micro,

nationalisation,

private goods,

privatisation,

public goods,

rival,

subsidies,

trains

Wednesday, 18 January 2017

Leaving a Customs Union - what it means

This article covers aspects of Brexit immediately after Theresa May's key speech. Some real gems in here - follow the link for short videos with more information:

After

months of vague and ambiguous statements about what Brexit actually means

(apart, of course, from Brexit), Prime Minister Theresa May laid out plans

for negotiations in a speech on Tuesday.

The Prime Minister confirmed

Britain will leave the EU single market and not remain a full member of the

customs union after Brexit, saying that she wanted the UK to be free

to set its own trade tariffs with other states.

This

will have several major implications. It will mean the country will no

longer benefit from the EU's trade deals with other nations. It could also mean

UK businesses face steep tariffs when exporting goods to the EU.

But

what is the customs union and what exactly will leaving it mean for people in

the UK?

What is the customs union?

The

customs union facilitates free trade between EU states by ensuring that they

all charge the same import duties to countries outside the union. The countries

also agree not to impose tariffs on goods travelling between countries in the

union.

Jeremy

Corbyn says Theresa May risks 'trade war' with Europe over Brexit strategy

The

agreement reduces administrative and financial trade barriers such as customs

checks and charges.

This

is different from a free trade area, which means no tariffs, taxes or quotas

are charged on goods and services moving within the area but allows its

participants to negotiate their own external trade deals.

It

is also not the same as the single market, which is broader, encompassing the

free movement of goods, services, capital and people.

The

European customs union is the largest in the world by economic output, which

gives it considerable negotiating power.

In

practice, it is possible to be outside the customs union but still have access

to the single market, as Norway is. This means it can negotiate its own trade

deals but has to accept free movement of people and must comply with EU

legislation - an option that would anger many UK Brexit voters.

Conversely,

Turkey, Andorra and San Marino have customs union agreements with the EU but

are not part of the single market. These agreements only cover certain goods.

Turkey's agreement with the EU for example, excludes agricultural products,

services and public procurement.

Brexit Concerns

What would leaving the customs union mean?

The

clearest effect of leaving the customs union is likely to be increased tariffs

leading to rising prices. EU officials have said that they will not give the UK

an easy ride, and the country cannot pick and choose which elements of the

union it wants to keep and which it does not.

In

practice, this means that if the UK restricts the free movement of people with

immigration controls it cannot have completely tariff-free access to the single

market. The cost of doing business will therefore rise, with those costs

ultimately being passed on to consumers.

Countries

Such as Switzerland and Norway do enjoy tariff-free access without being part

of the customs union but both accept free movement and make contributions to

the EU budget.

The

UK could negotiate a free trade deal with the EU, as Canada has recently done,

for example. This means the UK would have access to the single

market to sell its products but would not be part of it - ie, it would not have

to sign up to free movement of people. Agreeing such a deal could

take many years. The EU-Canada trade pact signed in October took seven years to

negotiate.

How big could the impact be?

A

huge 44 per cent of Britain’s exports go to the EU - £220bn out of £510bn -

according to the Office of National Statistics. They would be subject to import

tariffs as well as extra administrative costs.

If

the UK did not negotiate a more favourable trade deal with the EU, it would

have to trade on standard tariffs under World Trade Organisation rules.

An

analysis by The Independent found that the cost to Britain’s exporters

-- in extra tariffs alone -- would be at least

£4.5bn per year. This conservative estimate does not include the

difficult-to-measure costs of non-tariff barriers, such as the enforcement of

different market standards and regulations.

As

an example of how damaging a WTO scenario could be, the Nissan plant in

Sunderland, which has a workforce of 6,700, exported around 250,000

cars to the EU in 2015, around half of its output. Those exports would face a

tariff of up to 10 per cent outside the customs union unless a free trade deal

could be negotiated.

The

extra costs on companies could force them to relocate UK operations within the

EU after Brexit, potentially leading to job cuts.

In

Tuesday's speech, Ms May said she would pursue a free trade deal as an

alternative to membership of the customs union. Such a deal could significantly

lower tariffs though it may not match what the UK currently enjoys inside the

customs union.

What will the positive impacts be?

The

main positive put forward by hard-liners, such as Secretary of State for

International Trade Liam Fox,

is that Britain would be free to negotiate its own trade deals with non-EU

countries. This could allow the lowering of barriers elsewhere to help to make

up for any loss of trade with the EU.

However,

trade deals take a notoriously long time to negotiate - far longer than the two

years the Government has between triggering Article 50 and leaving the bloc.

The UK would also be in a far less advantageous negotiating position.

Being

the world’s largest economic trading bloc with 500 million relatively wealthy

consumers gives the EU hefty clout which the UK alone cannot match.

The

second positive put forward is that the country would not have to pay the £13bn

it paid to the EU for membership in 2015, though there would be other,

potentially huge, costs to businesses.

European

officials have also mooted charging an annual fee if the UK wants access to EU

markets to buy and sell its products but remains outside the customs union. The

Prime Minister warned on Tuesday that this would a be a "calamitous act of

self-harm" on the part of EU member states and threatened to ditch a deal

if it was seen as punitive.

Norway

is set to pay £140 per head for its access to the single market between 2015

and 2020. The UK currently pays £220, according to analysis by factchecking

organisation, Full Fact.

- More about:

-

Labels:

Brexit,

customs union,

EU,

Europe,

free trade,

single market

Sunday, 15 January 2017

Key themes for 2017 - context from John Mauldin

If you find it too heavy, leave the "Help From Washington" section out; it does give a good background to how hard it may be to get some policies through, but is not really useful for the exams.

The following sections cover China, energy markets, Europe and AI; these sections all contain the sort of elements your essays cry out for - strong contextual justification for the sorts of statements you love making, but never back up. There is potential for a one-grade lift in this material alone, if you get the right question (most questions are open enough that you have a range of topics you can discuss).

Your choice to read (as ever), but time is running out and you need to beef up your essays from AS to A2:

“The shift from sailing ships to telegraph was far more radical than that from telephone to email.”

– Noam Chomsky

I’ll organize this letter around four key themes that I think we will discuss frequently in the next 12 months: US politics, energy, China, and Europe. Then I’ll wrap up with an overarching problem that’s also an opportunity – if we treat it as one.

Let’s begin with good thoughts. Markets have rallied since November on the expectation that Trump and the Republicans will quickly enact a growth-oriented economic agenda, including tax cuts, regulatory relief, and targeted economic stimulus projects. As I talk to people involved in the transition, I am gaining more confidence that a good part of that agenda will actually be realized. It’s clear to me that the right people want it to happen, at least. Whether they will get what they want is a slightly different question.

One reason I’m encouraged is that the Republican majority doesn’t have to start over. They already did some of the heavy lifting in the bills that passed Congress for the last two years, only to see them vetoed by President Obama, and in bills that never got that far because a veto was assured. The Republicans know who does and who doesn’t support these bills. With some minor updating, they can quickly pass the bills again, with a better White House reception this time.

The GOP is also intent on hacking back some of the regulatory tentacles that have impeded progress (and especially job growth) in some industries. They intend to employ a rarely used law called the Congressional Review Act to reverse some of the Obama administration’s regulations. They are also considering legislation that would require federal courts to stop accepting federal agencies’ statutory interpretations and defer to Congress instead.

Tax cuts are almost 100% certain, though their beneficiaries are not certain at all. Constitutionally, all tax bills must originate in the House, and their impact on the deficit will be important to some House Republicans. Passing a tax cut may depend on having a corresponding set of spending cuts ready. Seriously, we simply have no idea how the tax issue is going to play out. Fixing taxes could be problematic: Every dollar the government now spends (or gives in tax benefits) helps somebody, and whoever it is almost certainly has lobbyists on retainer. Nevertheless, we will get a tax cut, though we may not know the nitty-gritty details for a while.

I’m told the Republicans have a long list of relatively uncontroversial (at least on their side of the aisle) bills that they can pass very quickly. They want to show progress, and they think quick passage of some popular measures will buy them credibility to use later. I expect an initial burst of activity after January 20, probably followed by a lull as the Congress moves into more contentious issues like Social Security and healthcare reform. Things will keep happening, but we may not see as many votes.

The hard part is getting agreement on the big items like taxes and healthcare reform. I love seeing Trump and Pence and Ryan and McConnell and all the guys holding hands and acting as if they’re all ready to walk into the bright new future together, but the reality is that there are some quite different ideas in Washington about what serious reforms should look like, and a lot of congressmen want to put their personal stamp on the final bills.

The reform effort could fall apart for various reasons. The Senate majority is narrow enough that just a handful of GOP defectors will be able to stop any given bill, assuming Democrats stay united in opposition. I think Republicans should be on guard against hubris, as well. The decision last week to kick off the year by softening ethics rules was a terrible idea. They accomplished nothing and energized an opposition that was otherwise on its heels. (And I know that many of us are uncomfortable with the concept of a Tweeter-in-Chief, but all it took was one tweet to kill that really bad idea. I mean, Trump stopped it dead in its tracks. Which I believe the vast majority of us will think was a very good thing.)

Finally, as I cautioned last week, there is always the chance that some “bolt from the blue” could change everything. An international crisis, a large bank failure, terror attacks – any one of a long list of unforeseeable events could conceivably derail this train. Not to mention the endemic problems of Europe and China, which we will deal with below and which are entirely foreseeable. But if we can get through the first 100 days with this administration, then I think its agenda will have enough momentum to keep rolling.

Assuming no major surprises, I think the tax and regulation changes can boost GDP growth in the final half of 2017 toward the 2½ percent range. That will be a small improvement from this year and could set the table for a bigger feast in 2018 and beyond. Much also depends on how the Federal Reserve responds, as well as on any changes in its composition.

But here again, if the Republicans get all timid or can’t cooperate and end up settling for the usual tinkering around the edges with tax reform and healthcare reform; and if they are stymied by an entrenched bureaucracy that doesn’t want to see its regulatory powers dismembered, then we can’t expect to get the economic boost that everybody is anticipating. If a policy-driven boost doesn’t materialize, the markets, which have jumped on the anticipation of Real Change, will reverse just as quickly.

That’s why I say, “Proceed with caution.” If my base case plays out and we get reasonable progress on healthcare reform along with regulatory reforms, the stock market could end the year higher, even from today’s elevated valuations; and earnings could really be improving by the third and fourth quarters – if the reforms are actually put into place in time.

If the reforms get hung up or are watered down and not really effective, this market could tumble out of bed so fast that it will make your head spin. I will be saying much more by March about how I think portfolios should be constructed, but my current core portfolio is basically long most of the US market (and long selectively all over the world as well) and has sidestepped the bond market (with some exceptions). All of that could change quite quickly – it’s no surprise to longtime readers that I think portfolios should be actively managed.

That said, passive management will also continue to work if my base-case scenario comes about, and that outcome will just convince more people to move their portfolios to passive management. A market mentor of mine, who had already been trading the markets for 50 years when he began to tutor me, always treated the markets as if they are a personality.

“The market will do whatever it takes to cause the most pain to the most number of people,” was the litany he repeated to me, over and over. The more people that are lured into the grip of passive investing, the greater the pain will ultimately be – which means that this market can go sideways for a lot longer than many of us who have a cautious nature can imagine. We are truly in new territory.

Energy stocks have been tearing higher since the election on bets that the Trump administration will relax environmental restrictions and open more federal lands to oil and gas drilling. Crude oil’s staying north of $50 hasn’t hurt, either. It is up there in part because OPEC threw in the towel and agreed to production limits. Unfortunately for OPEC, those limits don’t apply to US and Canadian shale producers. And the history of OPEC is that they all cheat like crazy.

My friend Art Cashin has an internal “friends and family” list to which he generally sends one or two short, pithy notes per day. For quite some time now, he has been noting the high correlation between the price of oil and the stock market. That correlation is why I have moved my thoughts on energy closer to the front of the letter. The price of energy is important to our portfolios in ways that are not clearly understood but can be observed.

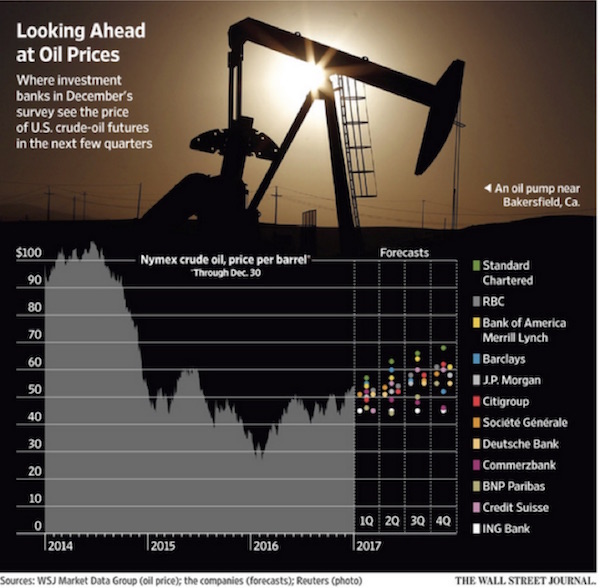

I think it is entirely possible that we will see oil prices climb somewhat further by mid-year, possibly approaching $60, and then pull back as capped US production comes back online. Look at the chart below to see the wide variation among forecasts of major energy analysts working for the big banks.

I also think that this year we’ll start to see a new pattern: Production could keep rising even as prices fall. Conventional wisdom says that producers stop pumping at some point when it becomes unprofitable, but I think that is about to change.

If you are an oil producer – or really, any commodity producer – two things can improve your profit margin: higher selling prices for the resource you produce, or lower production costs. Some combination of both works as well.

Now, selling prices are mostly outside the producer’s control, though adept hedging can help. Cost reduction is therefore the place to concentrate your attention. Back in 2015 I wrote about new drilling techniques and other technology that promised to bring oil and gas production costs significantly lower. Now, in the last few weeks, people in the business have told me these technologies are moving rapidly toward deployment. They foresee considerably lower drilling and production costs by the end of this year.

I had a confidential briefing recently about some new energy production processes that are coming online in the oil patch. Let me just say that production from an oil well drilled with these new techniques is getting ready to increase substantially. In some cases the amount of oil produced per dollar spent on drilling is going to more than double. There are significant chunks of the petroleum-producing parts of the United States where $40 oil will not be a barrier to drilling and new production. Eventually – in a few years – these techniques will begin to show up in wells around the world, and there will be an explosion of oil.

Even as many oilfields dry up, there will be new fields developed from previously unprofitable sources. As I’ve been saying for 15 years, the whole Peak Oil thing is nonsense. I used to think that it simply meant the price of oil would go up to justify the cost of drilling, but I didn’t really understand how much technology would lower the cost of drilling.

This technology trend means that the current oil price range may well break lower, perhaps this year but certainly within this decade, without energy companies losing profits. Not every company will reap the rewards equally, of course; but the industry as a whole is excited. Energy exploration and production is quickly becoming a technology-driven industry, with the US as world leader. If Trump permits construction of more pipelines and natural gas export terminals, we could see North American exports rise considerably in the next few years.

Obviously, over time, a falling energy price will not be good for OPEC or for Russia. Those lower prices will create geopolitical challenges as well as economic ones. I don’t know how it will all shake out. We will likely see some big, energy-driven changes in the world order in the coming decades. But that is beyond the scope of an annual forecast.

Sidebar: every time I write about energy I get the following questions: “What about the environment? Won’t more oil and gas production aggravate climate change?”

Many wonder whether I care about the environment or accept the reality global warming. The simple and very short answer is that I can see the data as well as anyone, and I believe the Earth is in a warming cycle. I very much care about the environment. I don’t want to see the air I breathe or have polluting chemicals in the water I drink. We only get the one Earth, and we have to take care of it.

My full answer is longer and, as you might suspect, more complex. It will end up being a chapter (or a significant part of one) in the book I am writing, called The Age of Transformation. It will be out this year, and hopefully by the time of my conference, if I can at all get it all wrapped up. If you meet me at SIC and we have time for an extended conversation, feel free to ask about these issues. No one-paragraph answers will suffice. Now back to our forecasting.

This is going to be a pivotal year for China. Having to deal with a US president who refuses to play by Beijing’s rules is only part of it, and not necessarily the most important part. China has defied gravity in more ways than I can count. We will see if it can levitate another year or whether it falls back to Earth in 2017. My base case is that they continue the levitation act, but we are going to see an increase in volatility.

I’m not sure how many people are aware that the overnight rate for offshore yuan reached an incredible 105% at one point last week. The Chinese created a massive short squeeze, trying to maintain the value of the yuan. They have spent hundreds of billions of dollars in that effort and are likely to spend more this year.

The natural direction for the yuan, if it were allowed to float, would be significantly lower against the US dollar than it is today. The Chinese are manipulating their currency, but they are manipulating it to maintain its current value and allow it to slowly fall to its natural rate. Any precipitous move in the yuan can unsettle markets quickly.

Further, some $2 trillion worth of Chinese currency has been converted into dollars and moved offshore in the last few years. Think about that in the context of quantitative easing and realize that individual Chinese wanting to move their money out of the country have almost as great an effect on the amount of money sloshing around the developed world as our central banks have. The sources of that money are another subject entirely, but it is enough to note that that money is out in the world, much of it in North America, much of it looking for a home, driving up prices of real estate and other assets.

The Chinese Communist Party will hold its 19th party congress in the fall and will almost certainly give Xi Jinping another five years at the helm. He has become China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping and could well surpass even Mao before he departs. It could be awhile before he does, too, if this party congress goes according to script.

Xi may need to exercise all his power if he is to maintain both economic growth and domestic order. Sagging exports and rising labor costs are causing manufacturers to turn to automation, but that shift creates unemployment. Xi’s government is doing all it can to keep the masses happy, mostly by handing out generous benefits and subsidies to the usual suspects, including state-owned enterprises. This help makes it very hard to tell which of China’s many state-owned enterprises are actually turning a profit vs. operating at a loss because officials have ordered them to. That is why state ownership is problematic, of course, but for China the alternative may be worse.

A major side effect is that all the stimulus sloshing through an economy with few international exits has nowhere to go. The Chinese have fairly serious limits on the amount of money that individuals can take offshore in a given year. That means there is a lot of money in China looking for a home.

The results are predictable: asset bubbles rolling through regions and asset classes whose valuations follow no discernable logic. These imbalances can’t continue indefinitely, but I don’t know how the Chinese will arrest them. The direct route would be a currency revaluation. That seems to be what they are attempting, albeit very slowly. Ironically, I believe that both Xi and Trump agree they don’t want the yuan to move downward all that much in the coming years.

Xi’s hands are tied: Propping up the value of the yuan is going to force him to use his dollar reserves or to raise interest rates in an already volatile market. The Chinese are getting to a place where manipulation will be a lot more difficult than it has been in the past.

China is trying to do something that would be hard no matter who is in charge. The US is the world’s largest economy because we create most of our own supply and demand. It took us many decades to reach that point; China is trying to do it in about two decades. Their export-heavy model can’t work much longer, but they don’t yet have a way to create sustainable internal demand.

A consumer economy is the opposite of what China has been for the last 30 years of its journey toward becoming a capitalistic society. The export-led model works for the first three stages of national economic development, but it is not what you need to get to and through the last two stages, as I have written in the past. This transition is going to be far more difficult than anything China has faced for a very long time.

Maybe Xi will balance his massive economy perfectly and skip right over the painful adjustments that developing nations (including the US several generations ago) typically go through. I certainly wouldn’t bet against that possibility. The Chinese have been doing things that nobody thought they could do for quite a few decades now. But I won’t bet for it, either, especially this year. All the conditions are in place for major problems in China. That 6.5% GDP growth rate, even if it’s close to correct (and I don’t believe it is), can’t go on forever.

China’s problems are everyone’s problems. I saw a report last week estimating that $1.5 trillion, yes trillion, in corruption proceeds escaped China between 1995 and 2013. That is in addition to the legal money coming out of the country. Most of it landed in the US, Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands, where it has helped to inflate some of our own asset bubbles. In my travels, I constantly run into people who tell me they manage Chinese money. Not trillions, just $50 million or $100 million here and there. It adds up. How much is really out there? I don’t think anyone knows, but it’s a big and growing number.

Our fifty states are essentially what the European Union’s founders wanted: a giant free-trade zone with a currency union and fiscal union. It’s working for us in part because our states, while unique, don’t have the centuries of cultural and linguistic diversity that Europe’s do. I think we underestimate how important our common language and heritage have been to our economic development.

The separate languages, cultures, and histories of its nations don’t mean Europe can’t develop better ways cooperate economically; but the EU structure, specifically the European Monetary Union and the euro, clearly isn’t the answer. I think 2017 will make this fact increasingly obvious to everyone – and possibly undeniable if the worst happens in Italy. Let’s start there.

Italy’s banks are holding something like €350–400 billion in nonperforming loans, depending whose numbers you believe. The vast majority of that amount is not just temporarily NPL; it’s dead money, up in smoke. The banks are pretending otherwise, and the government is letting them. So is the ECB. This is a fact Europe must face. Yet no one wants to face it, and so the leadership is trying to pull off an increasingly ludicrous shell game.

We forget sometimes that banks are themselves borrowers. Most of their lending capital is not equity. They get it by taking deposits and issuing bonds. If a bank can’t collect on the loans it made, it can’t repay the money it has borrowed, and the whole edifice collapses. Bank collapse is ugly, and minimizing the ugliness is one reason we have central banks. We expect our central bankers to remain sober even while everyone else imbibes.

The European Central Bank may be sober, but I’ll bet more that than a few of its member countries would like a drink. Especially in Italy. They are in a near-impossible situation. Huge imbalances exist within the eurozone with no mechanism to resolve them, and Italy is one of the southern-tier countries that is bearing the brunt. That’s not the ECB’s fault. The system was never going to work. Now people are realizing it’s broken, and they are fighting to get out with what they can.

Inflation last month finally reached 1.7% in Germany. You can bet the drumbeat for tighter monetary policy, in place of the all-out massive quantitative easing that we are currently seeing, is going to grow louder in Germany and most of the other northern countries. That is exactly the opposite of what Italy and the southern countries need. See the potential for conflict?

Last week I saw a Spectator article that was not encouraging. I can’t say the following any better than the writer, James Forsythe, did, so I will just quote him.

After the tumult of 2016, Europe could do with a year of calm. It won’t get one. Elections are to be held in four of the six founder members of the European project, and populist Eurosceptic forces are on the march in each one. There will be at least one regime change: François Hollande has accepted that he is too unpopular to run again as French president, and it will be a surprise if he is the only European leader to go. Others might cling on but find their grip on power weakened by populist success.

The spectre of the financial crash still haunts European politics. Money was printed and banks were saved, but the recovery was marked by a great stagnation in living standards, which has led to alienation, dismay and anger. Donald Trump would not have been able to win the Republican nomination, let alone the presidency, without that rage – and the conditions that created Trump’s victory are, if anything, even stronger in Europe.

European voters who looked to the state for protection after the crash soon discovered the helplessness of governments which had ceded control over vast swathes of economic policy to the EU. The second great shock, the wave of global immigration, is also a thornier subject in the EU because nearly all of its members surrendered control over their borders when they signed the Schengen agreement. Those unhappy at this situation often have only new, populist parties to turn to. So most European elections come down to a battle between insurgents and defenders of the existing order.

As James Forsythe says, the conditions that won Donald Trump the presidency exist in Europe as well and are possibly even stronger there. They manifest differently under parliamentary systems, but I see no chance that they will go away. They’re getting stronger, and I think we’ll see proof when France, the Netherlands, and Germany hold national elections this year. It is likely that the Italians will also have to hold snap elections because of the banking crisis, and it is not entirely clear that a majority would support a referendum on remaining in the euro (which is different from remaining in the European Union).

The anti-EU, anti-immigration parties may not win outright control in any of the four countries, but they can still exert enormous influence. These parties may not have the solutions, but the incumbents definitely don’t have them. Given a choice between unlikely and impossible, you have to go with unlikely. That’s what Europeans are doing.

I expect 2017 to bring many changes to Europe, but I’m not convinced it will be the end just yet. “Delay and distract” has worked well for the pro-EU, pro-euro forces ever since the sovereign debt crisis hit in 2010. The europhiles are true believers who simply won’t give up. At some point their determination may not matter, but I suspect they can keep doggedly kicking the can down the road until 2018 or later. It is just not clear when they will run out of road.

When they do, the result will likely be a very severe recession in Europe, which will embroil the world and could push the US into recession if it happens too quickly. Perhaps if we muster the reforms we need here in the US and actually get some sustainable growth going, then a fragmenting Europe might just knock that growth back to the sub-2% or even sub-1% range. But if China, too, loses the narrative in 2017, then all bets are off.

Like it or not, we have entered an era in which machines are learning how to do much of the work that now provides our incomes and, in many cases, our self-worth. This is a topic we will explore in depth in future letters. But a brief summary needs to be interjected here.

The US is manufacturing more materials and goods than ever. Manufacturing is increasing at a fairly serious rate, well over 2% a year. The problem is, manufacturing jobs are not. A Ball State University study calculated that it would take more than 8 million additional jobs to produce what we currently produce today if we were merely at the productivity levels of 15 years ago.

Investment in automation and software has doubled the output per U.S. manufacturing worker over the past two decades. Robots are replacing workers, regardless of trade, at an accelerating pace. “The real robotics revolution is ready to begin” writes BCG and predicts that “the share of tasks that are performed by robots will rise from a global average of around 10% across all manufacturing industries today to around 25% by 2025.” (Source: fortune.com/2016/11/08/china-automation-jobs/)

This is a simplification, but robots and their associated machinery have been somewhere in the neighborhood of four times more important in the loss of manufacturing jobs than off-shoring of jobs has been. But it is hard to protest against increased automation and easier to point a finger at China or Mexico.

The real challenge the US and the rest of the developed world face is how to create new jobs in the face of this automation challenge. The problem is not one we can walk away from. The best estimates that I have read suggest that Korea may be 15–20% more productive than we are in terms of costs, because they are pushing further and faster into the automation process. That trend will leave US manufacturers and exporters – or those in Germany or Italy or any other developed country – behind in the global business contest. Think Japan is not seeing the same thing?

If we don’t automate faster, we lose jobs by being uncompetitive. If we do automate, then we see jobs go away. What we have to do is figure out how to make sure that new jobs are created, and that these jobs are simply not make-work but are rather meaningful and fulfilling. Tall order. For whatever it’s worth, we are programmed in our evolutionary DNA to value what we contribute to the community through our work. Simply getting welfare without a way to eventually make it on your own does not help personal self-esteem or your community.

Incidentally, in the process of writing a book on how the world will change in the next 20 years, with over two dozen chapters on all aspects of the transformation before us, the single biggest and most difficult challenge has been this very topic. One of the reasons the book isn’t finished yet is that I’m still trying to get my head around this very problematic issue. It is at the core of how our society will evolve … or devolve. Not all the paths forward are good ones, and it is critical that we make the right choices.

I gained a new appreciation for the social and political crossroads we are at when I wrote last year about the “Unprotected” voters (to use Peggy Noonan’s term) who flocked to Donald Trump and (to a lesser extent) Bernie Sanders. Both of those men understand that unemployment and underemployment don’t simply reduce people’s incomes, though that’s bad enough. People want to be real contributors to the economy, but the economy increasingly tells them they aren’t necessary.

I’ve been told by people in the transition team that Trump and those around him are laser-focused on restoring jobs and creating new ones, particularly in the Rust Belt states. I have been having more than a few off-the-record conversations with members of the team, and they leave me at least somewhat optimistic that they are thinking about the right problems. It is also clear that they are looking hard for solutions. This is only part of the reason why Trump is pressuring companies to keep jobs in the US. He knows the numbers are small. He’s trying to force a wider change. And the staff around him get this focus.

If Trump succeeds at boosting US jobs, the problem may just be offloaded elsewhere if unemployment rises in Mexico and other places where US companies once operated. We need solutions that bring in the tide and lift all boats at once. Otherwise, conflict will continue and worsen in many different ways and places.

As an economic matter, lower costs and higher productivity are deflationary. Excess supply in the absence of higher demand pushes prices downward. This is why we’ve seen such sluggish growth in the last decade. At some point, faltering growth may turn into outright contraction on a global scale. Then the real problems will begin.

For those of you with some classical economics training, it is as simple as the supply-demand lines that we drew in Economics 101. If you push the supply curve to the right, you are going to find that you are in a new price equilibrium. I am really coming to believe that it is this process that has been (at least partially…) responsible for the lack of inflation that we have seen in the past 15 years. I suspect it has a bigger role to play even than interest rates, though I have no real justification other than personal, anecdotal observation to make that point.

At some point this year, we will be talking about why the whole theoretical construct that nearly all economics is founded upon, that of a dynamic equilibrium, is a false premise. The base case for the economy is not equilibrium, no matter how you define it, but rather constant change and near chaos. Part of the reason that dynamic equilibrium models work so well in theory is that we actually have the mathematics to create them. The fact that these models are perpetually wrong should give us a clue that something else is going on for which we don’t have the math or even sufficient fundamental insight.

This discussion will not only bring us back to Hayek but forward to complexity mathematics and information theory, and I believe all three in combination hold a better way to explain the workings of the economy.

Mainstream economics keeps using the same models and theories, or variations on those theories, but some of the underlying premises of Keynes are simply wrong (not everything of course; he was a brilliant man for his times); and nothing built on a foundation of faulty premises is going to allow you to model the economy in any really useful manner. There’s a lot to tackle with this topic, but it will be fun to try to gain some insight together.

Let me warn you, there are no simple solutions or silver bullets. I’m reminded of the old Blackadder skit where the hero is handed a blank sheet of paper and told that it’s the map to where he is going. When he points out that there is nothing on the page, the man says, “Of course, you have to fill it in. Nobody’s been there” (paraphrasing of course).

2017 will certainly allow us to fill in a lot more of our map. But none of us have ever been there. It is my hope that 2017 will be the year when we start to recognize our true potential for abundance and begin adapting to it, in a way that everyone benefits.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)