The Employment Numbers Say a Rate Hike Is Pretty Much Done

Let’s rewind the tape from an email sent out by Philippa Dunne of the

Liscio Report so we can see where the new jobs came from:

Employers added 271,000 jobs in October, all but 3,000 in the private sector. Construction added 31,000 (well above its average of 19,000 over the last year, though two-thirds of the gain came from nonres specialty trade, those who finish buildings); wholesale trade, an above-average 10,000; retail, 44,000, also well above average; finance, 5,000, less than half its recent average; professional and business services, 78,000, well above-average; education and health, 57,000, somewhat above average; and leisure and hospitality, 41,000, also somewhat above average. Government added 3,000, all from state government; local was unchanged, and federal, off 2,000.

Manufacturing was unchanged.

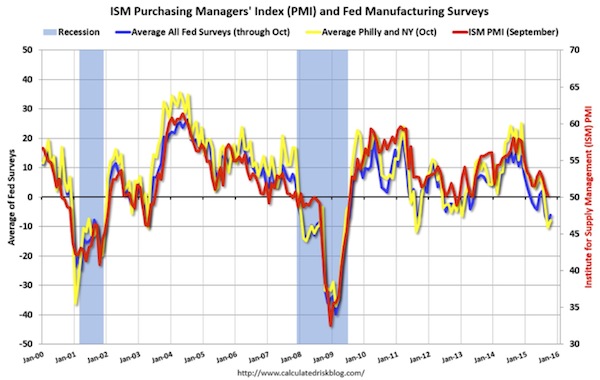

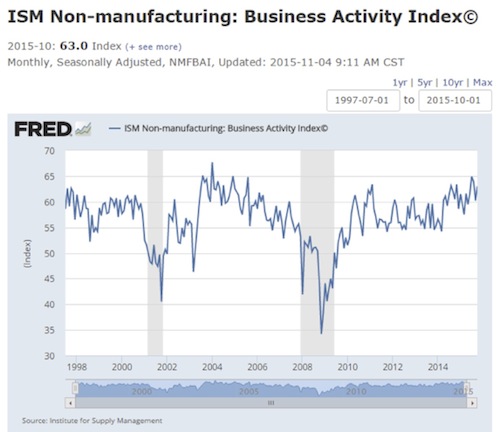

This employment report was all about gains in services industries, plus a little in construction. Which squares with the data we have seen in recent months from the regional Fed banks. Manufacturing is getting soft, and services are doing well. Let’s look at a few charts that will help tell the story. The first is an amalgamation of the regional Fed manufacturing indexes. The second is the national manufacturing index, and the last one is the national non-manufacturing (read services) index.

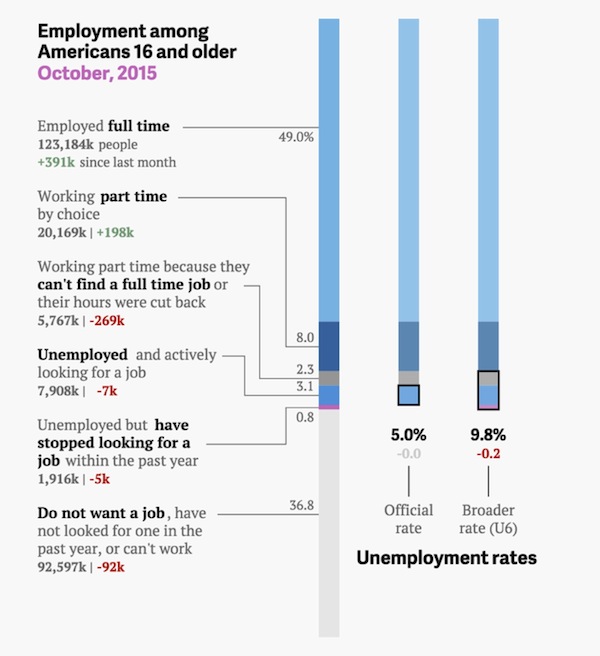

In researching this piece I also came across a very useful chart that breaks down unemployment by type. Let’s go straight to it and then add a few comments.

First, the above graphs look at both the official unemployment rate and the broader rate, which is called the U6 rate. The gap between the two measures is now the smallest in more than seven years, a sign that slack in the labor market is diminishing. And as the Fed weighs a potential rate hike, what may be more important is the number of people working part-time who would prefer to work full-time – that number posted its biggest two-month decline since 1994. Janet Yellen has referred to this number as often as she has to any other specific number. It is on her radar screen.

I’m in Miami, where I’ll be speaking at a conference where my friend David Rosenberg will also present. David has been predicting wage-push inflation from a tightening labor market for over two years now. He kept talking about the data, and I would look at it, but my old eyes couldn’t see the same trend or interpret it the way he did. And I admit I may have teased him about the lack of actual follow-through on that bit of data. Today’s data suggest that even though it’s a little early to declare a trend, there is clearly a hint of wage-push inflation in the air. David may even start taking victory laps. The labor market is getting a little tighter; and for reasons we’ll go into below, it may be even tighter than is apparent from the nonparticipation rate. So David may very well be right. Finally.

As my friend Joan McCullough writes:

Wage growth: +2.5%. Can you smell the wage-push? That’s the intention, so get used to it. So while extremely premature based on the metrics provided yesterday, not the least of which is wage growth in the 3.5 to 4% range as desirable to achieve 2% inflation, this is a start. And as you know, the FED only needs a “start.”

Behind the Unemployment Numbers

When we look at employment stats, we can easily forget that these percentages are not just numbers. Each category includes real people. Some are happy with their employment classification, but many aren’t.

The BLS data don’t capture every nuance. Frankly, that would be an impossible task. Laid-off factory worker Bob who sweeps floors at minimum wage 40 hours a week while struggling to avoid foreclosure is “employed full-time.” Attorney Bill with a six-figure income and two paid-for homes is also “employed full-time.” Bob and Bill are in wholly different circumstances, but we don’t see that in the data. We have no good numbers on how many of the 149.1 million employed people look like Bob vs. Bill. Income statistics help, but plenty of financially stressed people have above-average incomes. And the income data used in “research” is often distorted by political agendas. Income data is one example of the sort of statistics that you can torture to make the numbers say what you want them to say.

The BLS data does give us insight into some other employment categories, and that’s what I want to discuss today. We will see how many people find themselves in less-than-ideal circumstances and consider why they are there.

Who Is Unemployed and Why?

The Labor Department’s monthly figures come from surveys of both households and employers. Data from the household survey is what gives us the unemployment rate.

The October BLS summary table tells us the civilian noninstitutional population was 251.5 million. This is everyone age 16 and over who isn’t in the military, imprisoned, hospitalized, in a nursing home, or otherwise separated from society. That is out of a total population of some 319 million.

The “labor force” is a subset of the civilian noninstitutional population. If you are willing and able to work, you’re part of the labor force. The headline unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force not working when surveyed last month. For October, 7.9 million unemployed in a labor force of 157 million gave us 5.0% unemployment.

Why are these people unemployed? BLS actually gives us considerable detail, but the media seldom dig that deep. Looking at the seasonally adjusted numbers in

Table A-11, we see six categories.

• 933,000 were on temporary layoff from permanent jobs.

• 2.1 million were “permanent job losers,” meaning they previously had jobs but left them involuntarily.

• 899,000 had completed temporary jobs without finding new work.

• 789,000 were “job leavers” who voluntarily quit their last jobs.

• 2.4 million “reentrants” had left the labor force but were now looking for work again.

• 807,000 “new entrants” had never worked but were now looking.

[Note: I know the numbers don’t add up precisely. I think that’s because of a seasonal adjustment.]

Now, you can be unemployed without being “unemployed.” This is where it gets confusing. Retirees, full-time students, non-working parents, and others not working or seeking work are “not in the labor force.” They are neither employed nor unemployed.

This category has bedeviled economists since the last recession. The data is in

Table A-16 of the BLS report. What are these 94.2 million people doing if they aren’t working? The number has been growing the last few years, but that might be because baby boomers are reaching retirement age.

More interesting is the subcategory of 5.7 million who say they want a job but are not actively looking for a job. How can those two things go together in the same person?

Last month BLS classified 1.9 million of the not-in-the-labor-force people as “marginally attached.” That means they want a job, have searched for work in the last year, and would take a job if they were offered one, but haven’t actively looked for work in the last four weeks.

Within the marginally attached category are 665,000 “discouraged workers.” They didn’t look for work (quoting BLS) “for reasons such as thinks no work available, could not find work, lacks schooling or training, employer thinks too young or old, and other types of discrimination.”

The other 1.3 million in the marginally attached group didn’t look for work, either, but “for such reasons as school or family responsibilities, ill health, and transportation problems, as well as a number for whom reason for nonparticipation was not determined.”

If we were to move the marginally attached people into the labor force as unemployed, the unemployment rate would look significantly worse. The size of the labor force would go up from 157 million to 159.2 million, and the number of unemployed would rise from 7.9 million to 10.1 million. That would make the headline unemployment rate 6.3% instead of the 5.0% BLS reported for October.

Conversely, if there were a way to address the issues that keep these people only marginally attached, the number of employed people would go up, and the unemployment rate would fall.

So what barriers leave so many people marginalized? I’ll list three that I think account for a significant part of the group. We have some hard data, but there will also be some speculation on my part. I’ll be curious to know whether your impressions match mine.

Unemployment in America Is a Felony

It has been a very long time since I submitted a resumé or filled out a job application (which is a good thing, because I think I’m essentially unemployable). My adult children and their friends tell me that almost every employer now wants to know if applicants have any criminal convictions in their background. Some even ask if the police ever arrested you, regardless of the outcome.

Thanks to the Internet, employers can and do run background checks on applicants, even if they don’t ask questions directly. Your odds of being hired drop sharply if they find anything.

How sharply? This is hard to pin down. Discriminating based only on a criminal record is illegal in many places, so hiring managers won’t admit to doing it. In any case, they can always find plausible reasons to put such applicants at the bottom of the pile. The effect is the same.

This is not a small problem. Pool data cited in a

New York Times story last February revealed that 34% of all non-working men ages 25-54 had a criminal record. Is that the reason they aren’t working? We can’t say for sure, but I would bet it is a huge factor.

Thinking as an employer, I can understand why this happens. Legal liability is a big concern. If you own a repair service and your workers go into people’s homes, of course you don’t want to hire ex-thieves. If your workers drive business vehicles, you would be nuts to hire someone with DWIs or drug convictions. When you are looking at 10 applications for every job, it is easy to throw out the 34% that have felony charges. Boom. Gone. Look elsewhere.

At the same time, does it make sense to arbitrarily rule out an otherwise qualified applicant simply because of a youthful mistake? No, it doesn’t. The problem is that a prospective employer doesn’t know the individual’s story and doesn’t have time to find out.

I happen to know more than one young adult who’s stuck in that employment category. You probably do, too. They apply for jobs, get positive feedback… and then the employer suddenly loses interest without saying why.

It is extremely hard to stay motivated when this happens repeatedly. What can you do? The conviction will follow you forever. I would bet this explains a big part of the “marginally attached” group. They would work if anyone offered, but they have little incentive to search. They fall back on crime, welfare, or the kindness of family.

It is not just jobs. Most of the nicer apartment complexes in Dallas will not allow anyone with a criminal record to rent. My suspicion is that the situation is similar in the rest of the country. What happens is that we end up creating “ghettos” in certain areas where housing providers will rent to former felons and those who were merely charged with a felony in the past. Getting those records expunged is expensive and difficult.

And while I’m on the topic, the way we treat ex-felons in the justice system is criminal. I personally know of a gentleman who had a youthful drug issue, did his time, got out of prison, and, because he was a jack of all trades, was able to get work fixing things here and there. It was enough to put a roof over his head and feed his two teenage daughters, who were trying to finish high school. But the State of Oklahoma decided that he needed to pay $1000 in fines and reincarcerated him for six months. (Which probably cost them, say, $15,000?) There was no one to take care of his daughters, no one to pay the rent, and so on. This story is repeated all over America every day. The criminal justice system in the United States is more than broken, and it has gotten to the point where it’s more than blind; it’s simply dumb. Three percent of the country is either in jail, on probation, or on parole.

The only solution I can imagine would be a much stronger economy accompanied by labor shortages. Employers would then have incentives to accommodate less-than-ideal applicants, who frankly might have more incentive than most to work their derrieres off.

“Family responsibilities” that prevent you from working are another way to land in the marginally attached group. This can describe many situations, of course. Childcare is a big one.

I know families who still match the traditional pattern: Dad has a job; Mom stays home with the kids. I know stay-at-home dads, too. They are the exception. Most families seem to need two incomes to support even a modest lifestyle. If both parents work, who takes care of the children all day? Especially if Grandma lives across the country?

Decent,

professional childcare isn’t cheap. I know people who spend $1,000 per month per child. That’s for just a drop-off day care center. A full-time, reliable nanny costs much more.

As a strictly financial matter, paying that cost makes sense only if it allows one parent to recover the childcare costs plus earn quite a bit more. The job income will be taxable, too, while the imputed income from providing your own childcare is tax-free.

Suppose you have two preschool children. Mom has a $4,000/month job offer. To take it, she must spend as much as $2,000 on childcare. She’ll spend probably $1,500 more on taxes, commuting costs, and work clothes. Should she take the job? Probably not. Or she could cut back on the quality of the childcare she invests in and deal with guilt and worry about her children.

On the other hand, working when you break even or even lose a little can make sense if you continue to accrue retirement, keep your health insurance, and maintain an employment record that will lead to better-paying jobs in the future. When you stay home with the kids for a few years, it’s hard to regain that ground professionally. The economic impact of the choice to work or not to work is not limited to the years when the kids need childcare.

Deciding not to work puts the woman in the “marginally attached” category. She might work if a much-better-paying job came along, but she doesn’t actively look for one. I think this is a very common scenario that explains a substantial fraction of the “marginally attached” category.

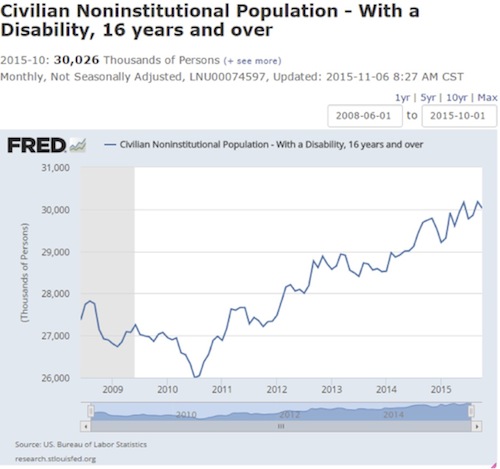

To be in the labor force, you must be physically able to work. You have no doubt seen stories about the sharp rise in disability claims since the last recession. Are that many people really disabled? Fourteen million get a disability check. About 57 million people – 19 percent of the population – had a disability in 2010 (the latest statistic I could find), according to a broad definition of disability, with more than half of them reporting that the disability was severe.

Here again, we don’t have good data. State governments and the Social Security Administration have a process for investigating disability claims, and I’m sure some people file false claims. The agencies probably do their best, but they can’t catch every fraudulent claim.

People who are legitimately disabled may or may not be in the labor force. They can earn small amounts without affecting their benefits. I think this is a good thing. The work gives them something to do and probably makes an otherwise hard life a little more bearable. A story came out this week that fits right in here.

Princeton economist Angus Deaton and his wife, Anne Case, also a Princeton economist, published a paper with surprising mortality data. Deaton, by the way, was recently in the news as the 2015 Nobel laureate in economics.

Their paper looks at death rates for middle-aged (ages 45–54) white Americans. They found a sharp increase in mortality rates between 1999 and 2013 for this particular group. The difference is stark and especially pronounced for those with lower education levels.

Even more surprising is what kills these people. It isn’t heart attacks or cancer. The most common causes of death were suicide, drug overdoses, and liver diseases linked to alcoholism.

Why are middle-aged white Americans dying at higher rates now? I can’t even begin to explain the racial aspect. Neither can Deaton and Case, apparently, but here is their economic speculation. I added some paragraph breaks.

Although the epidemic of pain, suicide, and drug overdoses preceded the financial crisis, ties to economic insecurity are possible. After the productivity slowdown in the early 1970s, and with widening income inequality, many of the baby-boom generation are the first to find, in midlife, that they will not be better off than were their parents.

Growth in real median earnings has been slow for this group, especially those with only a high school education. However, the productivity slowdown is common to many rich countries, some of which have seen even slower growth in median earnings than the United States, yet none have had the same mortality experience.

The United States has moved primarily to defined-contribution pension plans with associated stock market risk, whereas, in Europe, defined-benefit pensions are still the norm. Future financial insecurity may weigh more heavily on US workers, if they perceive stock market risk harder to manage than earnings risk, or if they have contributed inadequately to defined-contribution plans.

This makes sense, but I still don’t see why the same factors didn’t raise death rates for non-white Americans of the same age. But we certainly know that middle-class workers have massively underfunded their retirement programs.

How does this relate to employment? Among Deaton and Case’s cohort of 45 to 54 year olds, there were probably many people who didn’t work. They were chronically sick, addicted, mentally ill, or otherwise incapacitated. According to the statistics, there were many fewer such people 15 years earlier, but the apparent large increase calls into question much of our historical data.

Deaton and Case drill into the problem:

Our findings may also help us understand recent large increases in Americans on disability. The growth in Social Security Disability Insurance in this age group is not quite the near-doubling shown in Table 2 for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) measure of work limitation, but the scale is similar in levels and trends.

This has been interpreted as a response to the generosity of payments, but careful work based on Social Security records shows that most of the increase can be attributed to compositional effects, with the remainder falling in the category of (hard to ascertain) increases in musculoskeletal and mental health disabilities. Our morbidity results suggest that disability from these causes has indeed increased.

Increased morbidity may also explain some of the recent otherwise puzzling decrease in labor force participation in the United States, particularly among women.

By “morbidity” they mean sickness. The last line means they suspect people, especially women, are leaving the labor force for medical reasons.

You can

read the study online for yourself. It is only six pages. The paper is more readable than most economic research. It really throws a wrench into some common assumptions. Some 500,000 American workers who should still be with us are now dead. What would the unemployment rate look like if they were still alive and healthy? We can only speculate. Moreover, it seems like that millions more in this group are very unhealthy. They are out of the labor force, as are family members who care for them. They are also consuming healthcare and other resources. That’s not positive for anyone. We would all be better off if these people were healthy and working.

There are a lot of other factors, some of them anecdotal, that may contribute to the large number of people who are not participants in the labor force. I hear a lot about age discrimination against older workers – people who are 50+ but not yet of retirement age. Job coaches actually tell people not to go back more than 10 years on their resumés or to include college graduation dates. I imagine it’s easy for older job seekers to give up the search and try to live on their savings or under-the-table work until they can get Social Security.

Another subcategory in the “marginally attached” group might be those with specialized skills that aren’t in demand where they live. The factory closed, but you can’t move because your house won’t sell. Learning to do something different in the latter part of your work life can be challenging.

Then there are people who are in a gap between jobs. You quit job A and have job B lined up, starting next month. You aren’t employed now, but you aren’t looking for work, either. Thousands of folks probably fall in that group at any given time.

And as I mentioned, there are many people who are recovering from illnesses or caring for relatives. “I’ll start looking for work as soon as the doctor lets me.”

There is also the growing phenomenon of young people simply opting to stay home and not work. This from

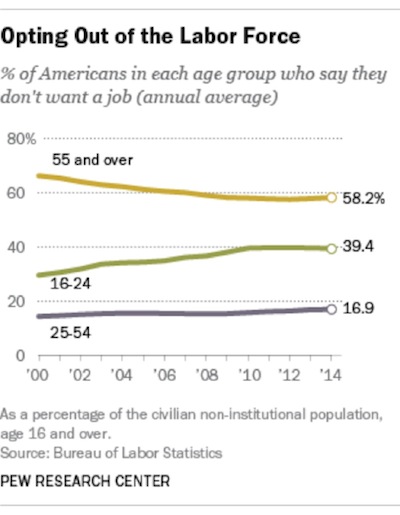

Pew Research:

[L]et’s look in particular at the youngest part of the eligible workforce. The share of 16- to 24-year-olds saying they didn’t want a job rose from an average 29.5% in 2000 to an average 39.4% over the first 10 months of this year. There was a much smaller increase among prime working-age adults (ages 25 to 54) over that period. And among people aged 55 and up, the share saying they didn’t want a job actually fell, to an average 58.2% this year.”

What we may be seeing at last is that many people who have been classified as “marginally attached” have already opted to go to work, along with many who were initially “not looking for jobs” and many who finally opted to take jobs at lower wages. So now, in order to entice additional workers, businesses may have to think about paying more money.

That is precisely what is supposed to happen in a tight labor market, and we have been waiting for one of those since the end of the Great Recession. Maybe the worker can finally catch a break. That would be good for everybody.