If you don’t think the transformation we’re embarked upon is a profound one, consider this: Within two decades, half the jobs in this country may be performed by robots. What then of our unemployment rate and social safety net? Opinion is divided: Will the next technological wave further skew the wealth distribution toward the uber-rich, or will it ultimately create more entrepreneurial and job opportunities than it destroys?

There is an interesting historical precedent for our situation, an era during which the technological firmament shifted just as abruptly as it is here and now. In the United Kingdom in the year 1800, the textile industry dominated economic life, particularly in Northern England and Scotland. Cotton-spinners, weavers (mostly of stockings), and croppers (who trimmed large sheets of woven wool) worked from home, were well compensated, and enjoyed ample leisure time.

Ten years later, that had all changed. Clive Thompson, the author of today’s Outside the Box, tells us what happened:

(I)n the first decade of the 1800s, the textile economy went into a tailspin. A decade of war with Napoleon had halted trade and driven up the cost of food and everyday goods. Fashions changed, too: Men began wearing “trowsers,” so the demand for stockings plummeted. The merchant class—the overlords who paid hosiers and croppers and weavers for the work—began looking for ways to shrink their costs.

That meant reducing wages—and bringing in more technology to improve efficiency. A new form of shearer and “gig mill” let one person crop wool much more quickly. An innovative, “wide” stocking frame allowed weavers to produce stockings six times faster than before: Instead of weaving the entire stocking around, they’d produce a big sheet of hosiery and cut it up into several stockings. “Cut-ups” were shoddy and fell apart quickly, and could be made by untrained workers who hadn’t done apprenticeships, but the merchants didn’t care. They also began to build huge factories where coal-burning engines would propel dozens of automated cotton-weaving machines….

The workers were livid. Factory work was miserable, with brutal 14-hour days that left workers – as one doctor noted – “stunted, enfeebled, and depraved.”… Poverty rose as wages plummeted.

Enter the notorious Luddites. Angry workers began to fight back, destroying the hated wide stocking frames and cotton-spinning machinery and even killing factory owners. Soon they were breaking at least 175 machines per month, and within months they had destroyed some 800, worth £25,000—the equivalent of nearly $2 million today.

As we know, the owners retaliated, the English government intervened decisively, and the Luddite rebellion was crushed. However, says Thompson,

At heart, the fight was not really about technology. The Luddites were happy to use machinery – indeed, weavers had used smaller frames for decades. What galled them was the new logic of industrial capitalism, where the productivity gains from new technology enriched only the machines’ owners and weren’t shared with the workers.

But will the Information Revolution that gave us computers, the internet, and social media – and the AI Revolution that is about to give us self-driving taxis and trucks and robot baristas – continue to lift our lower and middle classes, or further disempower and impoverish them?

When Robots Take All of Our Jobs, Remember the Luddites

What a 19th-century rebellion against automation can teach us about the coming war in the job market

Is a robot coming for your job?

The odds are high, according to recent economic analyses. Indeed, fully 47 percent of all U.S. jobs will be automated “in a decade or two,” as the tech-employment scholars Carl Frey and Michael Osborne have predicted. That’s because artificial intelligence and robotics are becoming so good that nearly any routine task could soon be automated. Robots and AI are already whisking products around Amazon’s huge shipping centers, diagnosing lung cancer more accurately than humans and writing sports stories for newspapers.

They’re even replacing cabdrivers. Last year in Pittsburgh, Uber put its first-ever self-driving cars into its fleet: Order an Uber and the one that rolls up might have no human hands on the wheel at all. Meanwhile, Uber’s “Otto” program is installing AI in 16-wheeler trucks—a trend that could eventually replace most or all 1.7 million drivers, an enormous employment category. Those jobless truckers will be joined by millions more telemarketers, insurance underwriters, tax preparers and library technicians—all jobs that Frey and Osborne predicted have a 99 percent chance of vanishing in a decade or two.

What happens then? If this vision is even halfway correct, it’ll be a vertiginous pace of change, upending work as we know it. As the last election amply illustrated, a big chunk of Americans already hotly blame foreigners and immigrants for taking their jobs. How will Americans react to robots and computers taking even more?

One clue might lie in the early 19th century. That’s when the first generation of workers had the experience of being suddenly thrown out of their jobs by automation. But rather than accept it, they fought back—calling themselves the “Luddites,” and staging an audacious attack against the machines.

**********

At the turn of 1800, the textile industry in the United Kingdom was an economic juggernaut that employed the vast majority of workers in the North. Working from home, weavers produced stockings using frames, while cotton-spinners created yarn. “Croppers” would take large sheets of woven wool fabric and trim the rough surface off, making it smooth to the touch.

These workers had great control over when and how they worked—and plenty of leisure. “The year was chequered with holidays, wakes, and fairs; it was not one dull round of labor,” as the stocking-maker William Gardiner noted gaily at the time. Indeed, some “seldom worked more than three days a week.” Not only was the weekend a holiday, but they took Monday off too, celebrating it as a drunken “St. Monday.”

Croppers in particular were a force to be reckoned with. They were well-off—their pay was three times that of stocking-makers—and their work required them to pass heavy cropping tools across the wool, making them muscular, brawny men who were fiercely independent. In the textile world, the croppers were, as one observer noted at the time, “notoriously the least manageable of any persons employed.”

But in the first decade of the 1800s, the textile economy went into a tailspin. A decade of war with Napoleon had halted trade and driven up the cost of food and everyday goods. Fashions changed, too: Men began wearing “trowsers,” so the demand for stockings plummeted. The merchant class—the overlords who paid hosiers and croppers and weavers for the work—began looking for ways to shrink their costs.

That meant reducing wages—and bringing in more technology to improve efficiency. A new form of shearer and “gig mill” let one person crop wool much more quickly. An innovative, “wide” stocking frame allowed weavers to produce stockings six times faster than before: Instead of weaving the entire stocking around, they’d produce a big sheet of hosiery and cut it up into several stockings. “Cut-ups” were shoddy and fell apart quickly, and could be made by untrained workers who hadn’t done apprenticeships, but the merchants didn’t care. They also began to build huge factories where coal-burning engines would propel dozens of automated cotton-weaving machines.

The workers were livid. Factory work was miserable, with brutal 14-hour days that left workers—as one doctor noted—“stunted, enfeebled, and depraved.” Stocking-weavers were particularly incensed at the move toward cut-ups. It produced stockings of such low quality that they were “pregnant with the seeds of its own destruction,” as one hosier put it: Pretty soon people wouldn’t buy any stockings if they were this shoddy. Poverty rose as wages plummeted.

The workers tried bargaining. They weren’t opposed to machinery, they said, if the profits from increased productivity were shared. The croppers suggested taxing cloth to make a fund for those unemployed by machines. Others argued that industrialists should introduce machinery more gradually, to allow workers more time to adapt to new trades.

The plight of the unemployed workers even attracted the attention of Charlotte Brontë, who wrote them into her novel

Shirley. “The throes of a sort of moral earthquake,” she noted, “were felt heaving under the hills of the northern counties.”

**********

In mid-November 1811, that earthquake began to rumble. That evening, according to a report at the time, half a dozen men—with faces blackened to obscure their identities, and carrying “swords, firelocks, and other offensive weapons”—marched into the house of master-weaver Edward Hollingsworth, in the village of Bulwell. They destroyed six of his frames for making cut-ups. A week later, more men came back and this time they burned Hollingsworth’s house to the ground. Within weeks, attacks spread to other towns. When panicked industrialists tried moving their frames to a new location to hide them, the attackers would find the carts and destroy them en route.

A modus operandi emerged: The machine-breakers would usually disguise their identities and attack the machines with massive metal sledgehammers. The hammers were made by Enoch Taylor, a local blacksmith; since Taylor himself was also famous for making the cropping and weaving machines, the breakers noted the poetic irony with a chant: “Enoch made them, Enoch shall break them!”

Most notably, the attackers gave themselves a name: the Luddites.

Before an attack, they’d send a letter to manufacturers, warning them to stop using their “obnoxious frames” or face destruction. The letters were signed by “General Ludd,” “King Ludd” or perhaps by someone writing “from Ludd Hall”—an acerbic joke, pretending the Luddites had an actual organization.

Despite their violence, “they had a sense of humor” about their own image, notes Steven Jones, author of

Against Technology and a professor of English and digital humanities at the University of South Florida. An actual person Ludd did not exist; probably the name was inspired by the mythic tale of “Ned Ludd,” an apprentice who was beaten by his master and retaliated by destroying his frame.

Ludd was, in essence, a useful meme—one the Luddites carefully cultivated, like modern activists posting images to Twitter and Tumblr. They wrote songs about Ludd, styling him as a Robin Hood-like figure: “No General But Ludd / Means the Poor Any Good,” as one rhyme went. In one attack, two men dressed as women, calling themselves “General Ludd’s wives.” “They were engaged in a kind of semiotics,” Jones notes. “They took a lot of time with the costumes, with the songs.”

And “Ludd” itself! “It’s a catchy name,” says Kevin Binfield, author of

Writings of the Luddites. “The phonic register, the phonic impact.”

As a form of economic protest, machine-breaking wasn’t new. There were probably 35 examples of it in the previous 100 years, as the author Kirkpatrick Sale found in his seminal history

Rebels Against the Future. But the Luddites, well-organized and tactical, brought a ruthless efficiency to the technique: Barely a few days went by without another attack, and they were soon breaking at least 175 machines per month. Within months they had destroyed probably 800, worth £25,000—the equivalent of $1.97 million, today.

“It seemed to many people in the South like the whole of the North was sort of going up in flames,” Uglow notes. “In terms of industrial history, it was a small industrial civil war.”

Factory owners began to fight back. In April 1812, 120 Luddites descended upon Rawfolds Mill just after midnight, smashing down the doors “with a fearful crash” that was “like the felling of great trees.” But the mill owner was prepared: His men threw huge stones off the roof, and shot and killed four Luddites. The government tried to infiltrate Luddite groups to figure out the identities of these mysterious men, but to little avail. Much as in today’s fractured political climate, the poor despised the elites—and favored the Luddites. “Almost every creature of the lower order both in town & country are on their side,” as one local official noted morosely.

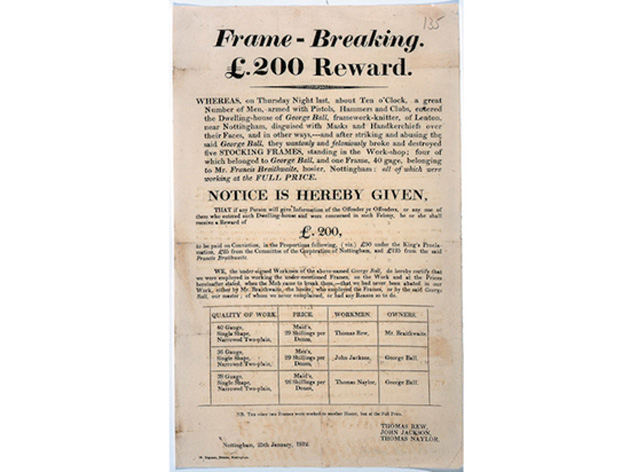

An 1812 handbill sought information about the armed men who destroyed five machines.

(The National Archives, UK)

**********

At heart, the fight was not really about technology. The Luddites were happy to use machinery—indeed, weavers had used smaller frames for decades. What galled them was the new logic of industrial capitalism, where the productivity gains from new technology enriched only the machines’ owners and weren’t shared with the workers.

The Luddites were often careful to spare employers who they felt dealt fairly. During one attack, Luddites broke into a house and destroyed four frames—but left two intact after determining that their owner hadn’t lowered wages for his weavers. (Some masters began posting signs on their machines, hoping to avoid destruction: “This Frame Is Making Full Fashioned Work, at the Full Price.”)

For the Luddites, “there was the concept of a ‘fair profit,’” says Adrian Randall, the author of

Before the Luddites. In the past, the master would take a fair profit, but now he adds, “the industrial capitalist is someone who is seeking more and more of their share of the profit that they’re making.” Workers thought wages should be protected with minimum-wage laws. Industrialists didn’t: They’d been reading up on laissez-faire economic theory in Adam Smith’s

The Wealth of Nations, published a few decades earlier.

“The writings of Dr. Adam Smith have altered the opinion, of the polished part of society,” as the author of a minimum wage proposal at the time noted. Now, the wealthy believed that attempting to regulate wages “would be as absurd as an attempt to regulate the winds.”

Six months after it began, though, Luddism became increasingly violent. In broad daylight, Luddites assassinated William Horsfall, a factory owner, and attempted to assassinate another. They also began to raid the houses of everyday citizens, taking every weapon they could find.

Parliament was now fully awakened, and began a ferocious crackdown. In March 1812, politicians passed a law that handed out the death penalty for anyone “destroying or injuring any Stocking or Lace Frames, or other Machines or Engines used in the Framework knitted Manufactory.” Meanwhile, London flooded the Luddite counties with 14,000 soldiers.

By winter of 1812, the government was winning. Informants and sleuthing finally tracked down the identities of a few dozen Luddites. Over a span of 15 months, 24 Luddites were hanged publicly, often after hasty trials, including a 16-year-old who cried out to his mother on the gallows, “thinking that she had the power to save him.” Another two dozen were sent to prison and 51 were sentenced to be shipped off to Australia.

“They were show trials,” says Katrina Navickas, a history professor at the University of Hertfordshire. “They were put on to show that [the government] took it seriously.” The hangings had the intended effect: Luddite activity more or less died out immediately.

It was a defeat not just of the Luddite movement, but in a grander sense, of the idea of “fair profit”—that the productivity gains from machinery should be shared widely. “By the 1830s, people had largely accepted that the free-market economy was here to stay,” Navickas notes.

A few years later, the once-mighty croppers were broken. Their trade destroyed, most eked out a living by carrying water, scavenging, or selling bits of lace or cakes on the streets.

“This was a sad end,” one observer noted, “to an honourable craft.”

**********

These days, Adrian Randall thinks technology is making cab-driving worse. Cabdrivers in London used to train for years to amass “the Knowledge,” a mental map of the city’s twisty streets. Now GPS has made it so that anyone can drive an Uber—so the job has become deskilled. Worse, he argues, the GPS doesn’t plot out the fiendishly clever routes that drivers used to. “It doesn’t know what the shortcuts are,” he complains. We are living, he says, through a shift in labor that’s precisely like that of the Luddites.

Economists are divided as to how profound the disemployment will be. In his recent book

Average Is Over, Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University, argued that automation could produce profound inequality. A majority of people will find their jobs taken by robots and will be forced into low-paying service work; only a minority—those highly skilled, creative and lucky—will have lucrative jobs, which will be wildly better paid than the rest. Adaptation is possible, though, Cowen says, if society creates cheaper ways of living—“denser cities, more trailer parks.”

Erik Brynjolfsson is less pessimistic. An MIT economist who co-authored

The Second Machine Age, he thinks automation won’t necessarily be so bad. The Luddites thought machines destroyed jobs, but they were only half right: They can also, eventually, create new ones. “A lot of skilled artisans did lose their jobs,” Brynjolfsson says, but several decades later demand for labor rose as new job categories emerged, like office work. “Average wages have been increasing for the past 200 years,” he notes. “The machines were creating wealth!”

The problem is that transition is rocky. In the short run, automation can destroy jobs more rapidly than it creates them—sure, things might be fine in a few decades, but that’s cold comfort to someone in, say, their 30s. Brynjolfsson thinks politicians should be adopting policies that ease the transition—much as in the past, when public education and progressive taxation and antitrust law helped prevent the 1 percent from hogging all the profits. “There’s a long list of ways we’ve tinkered with the economy to try and ensure shared prosperity,” he notes.

Will there be another Luddite uprising? Few of the historians thought that was likely. Still, they thought one could spy glimpses of Luddite-style analysis—questioning of whether the economy is fair—in the Occupy Wall Street protests, or even in the environmental movement. Others point to online activism, where hackers protest a company by hitting it with “denial of service” attacks by flooding it with so much traffic that it gets knocked offline.

Perhaps one day, when Uber starts rolling out its robot fleet in earnest, angry out-of-work cabdrivers will go online—and try to jam up Uber’s services in the digital world.

“As work becomes more automated, I think that’s the obvious direction,” as Uglow notes. “In the West, there’s no point in trying to shut down a factory.”