Most wood energy schemes are a 'disaster' for climate change

- 23 February 2017

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

Using wood pellets to generate low-carbon electricity is a flawed policy that is speeding up not slowing down climate warming.

Subsidies for biomass should be immediately reviewed, the author says.

Energy from trees has become a critical part of the renewable supply in many countries including the UK.

Critical role

While much of the discussion has focussed on wind and solar power, across Europe the biggest source of green energy is biomass.It supplies around 65% of renewable power - usually electricity generated from burning wood pellets.

EU Governments, under pressure to meet tough carbon cutting targets, have been encouraging electricity producers to use more of this form of energy by providing substantial subsidies for biomass burning.

However this new assessment from Chatham House suggests that this policy is deeply flawed when it comes to cutting CO2.

According to the author, current regulations do not count the emissions from the burning of wood at all, assuming that they are balanced by the planting of new trees.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images "It doesn't make sense," said Mr Brack, who is also a former special adviser at the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change.

"The fact that forests have grown over the previous 20 or 100 years means they are storing large amounts of carbon, you can't pretend it doesn't make an impact on the atmosphere if you cut them down and burn them."

"You could fix them in wood products or in furniture or you could burn them, but the impact on the climate is very different."

Mr Brack says the assumption of carbon neutrality misses out on some crucial issues, including the fact that young trees planted as replacements absorb and store less carbon than the ones that have been burned.

Another major problem is that under UN climate rules, emissions from trees are only counted when they are harvested.

However the US, Canada and Russia do not use this method of accounting so if wood pellets are imported from these countries into the EU, which doesn't count emissions from burning, the carbon simply goes "missing".

Burning wood pellets can release more carbon than fossil fuels like coal per unit of energy, over their full life cycle, the author argues.

Often the products have to travel long distances increasing the emissions associated with their production and transport.

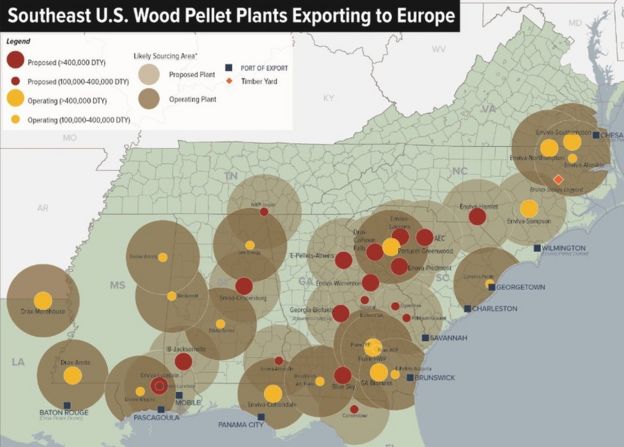

Image copyright Southern Environmental Law Center

Image copyright Southern Environmental Law Center "This report confirms once again that cutting down trees and burning them as wood pellets in power plants is a disaster for climate policy, not a solution," said David Carr, General Counsel of the Southern Environmental Law Centre in the US.

"Forests in our region, the southeast US, are being clear cut to provide wood pellets for UK power plants. The process takes the carbon stored in the forest and puts it directly into the atmosphere via the smokestack at a time when carbon pollution reductions are sorely needed."

Within Europe the push for pellets is also providing incentives for the forest industry to plant more and harvest more trees. Environmentalists are worried that the system is creating a cycle that can't keep up with itself.

"If you keep increasing your harvest over a period of time you will never be able to recoup your emissions from burning that growth, you will never catch up with yourself," said Linde Zuidema from Fern.

"They are shooting themselves in the foot, they are not taking into account that increased harvesting of trees will actually have an impact on the role that forests play as a carbon sink."

The new study also highlights concerns over the use of BECCS - bio-energy with carbon capture and storage.

Scientists, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), have suggested that this system could be used to suck carbon from the atmosphere to keep the world from dangerous levels of warming.

"It's really worrying," said Duncan Brack. "The number of scenarios that the IPCC reviewed that rely on BECCS for ambitious climate change targets, it's crazy, I'm not the only person who's said that."

Concern is growing about the continued use of wooden pellets and chips for electric power. The EU has proposed a new system for biomass under its revised Renewable Energy Directive.

Duncan Brack says it's a good opportunity to review the current methods of giving subsidies for the use of wood energy across Europe. The use of saw mill waste should be encouraged - but the burning of pellets should be curtailed.

"The simplest way is to limit support to those type of biomass that really represent genuine carbon savings, primarily sawmill waste and post-consumer wood waste," said Duncan Brack. "I would rather see support for forest industry, not forest energy."

Follow Matt on Twitter and on Facebook.

HS2 is monumentally wasteful, outdated, and will do nothing for the North – it must be scrapped