From John Mauldin's Outside The Box series. This is something you really should take the time to assimilate, as it brings together many disparate strands we have been discussing through Year 13:

Productivity: A Surprise Upside Risk to the Global Economy?

A bottom-up look at major industries around the world reveals significant potential for productivity growth.

By Matthew Tracey, Joachim Fels

May 2017

Is productivity dead? It is no secret that global productivity has languished in the post-financial-crisis years – with precious little evidence of a turnaround. If robust productivity growth were indeed a relic of the past, the long-term consequences for investors would be profound: Lower-for-even-longer interest rates would prolong the pain for yield-starved savers, pension funds and financial institutions; equity markets might underwhelm in a low-growth world; and PIMCO’s New Neutral might begin to look permanent.

But what if amidst all the doom and gloom there were a productivity-revival story in its infancy? That world would look starkly different. Imagine: World growth stages a comeback, interest rates normalize to the benefit of fixed income investors globally, and fears of secular stagnation give way to a renewed optimism in our future economic potential.

The productivity question couldn’t be more important. After all, there are only two ways to grow an economy: boost productivity, or grow the labor force (demographics). And we’re certainly not going to get much help from demographics. Fortunately, the upside potential for global productivity is growing (or, in economist-speak, productivity’s “right tail is getting fatter” – referring to the rising probability of a positive surprise in the range of outcomes). You might never recognize productivity’s upside potential, however, looking through the lens of macroeconomics alone. So let us look instead to microeconomics (sacré bleu!) for insights. Our thesis in a nutshell: Don’t rule out a global productivity rebound in the coming years that ushers in “old normal” (4%+) global growth. While a strong rebound is not PIMCO’s baseline view, it’s a tail that is fattening – and the microeconomic catalysts may have arrived.

Productivity optimists versus pessimists: clash of titans

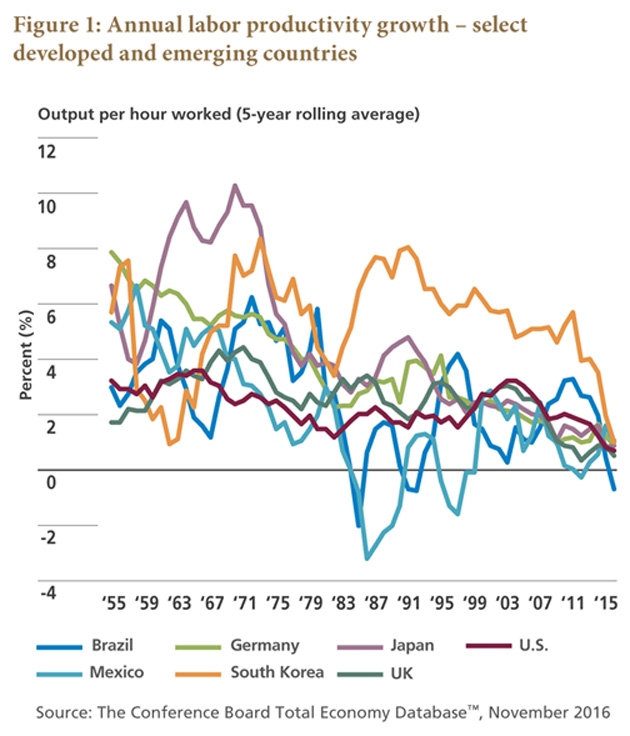

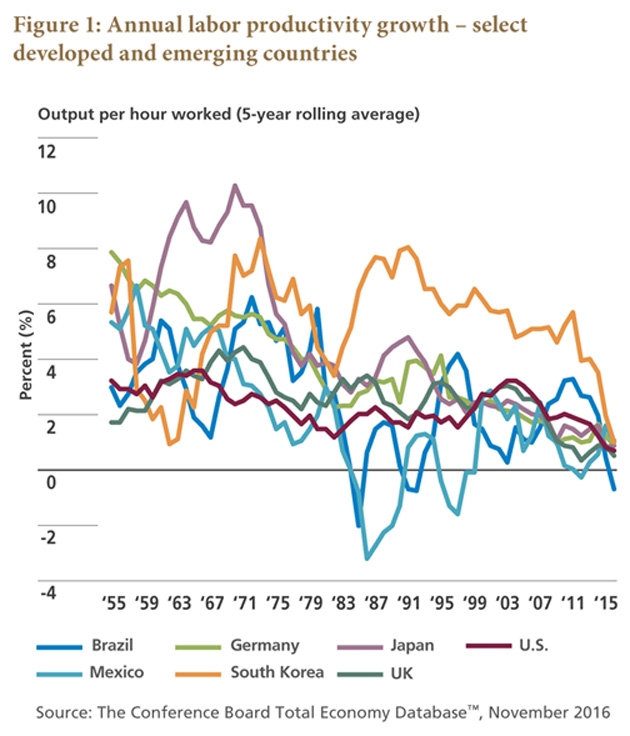

Labor productivity – or GDP per human hour worked – is in the dumps. Throughout the entire post-financial-crisis period we’ve observed declining productivity growth in economically significant countries worldwide (see Figure 1).

Productivity pessimists typically blame secular stagnation for the slump. Here, the arguments fall into two camps. “Demand-side” secular stagnation devotees, notably Larry Summers (a guest speaker at PIMCO’s upcoming

Secular Forum), suggest that a chronic deficiency of aggregate demand and investment is responsible for the dismal productivity growth we’ve seen in recent years … and that absent a rebound in demand, we’re doomed to more of the same. Meanwhile, “supply-side” secular stagnationists such as Robert Gordon believe innovation today isn’t what it used to be and that productivity gains from the computer revolution (formally, the “information and communications technology” or “ICT” revolution) have mostly run their course. Thes e supply-side pessimists argue that today’s innovations are mostly non-market – namely they help us enjoy our leisure time, but that’s about it (think iPhones loaded with fancy new apps). Gordon himself has suggested that “The future of technology can be forecast 50 or even 100 years in advance” and that he sees nothing on the horizon that will rival the breakthroughs of the past (see references list at the end of this paper – Gordon 2014).

Yet it is hard to look around and not see promising new technologies everywhere: self-driving cars, drones buzzing overhead and “smart” everything, to name just a few. Enter the techno-optimists: people who argue we’re on the cusp of radical breakthroughs that will drive huge gains in productivity and living standards. In our increasingly knowledge-based economy, they suggest, we’re moving from a zero-sum game of trade in goods to a positive-sum game of trade in information and ideas – with exponential benefits that our brains are not wired to foresee. (If you want to become a techno-optimist, read “Abundance: The Future Is Better Than You Think,” by Peter Diamandis and Steven Kotler.)

And so the debate rages on. It is certainly true that many consumer inventions – Facebook, Fitbit, Apple Watch and the like – don’t help workers produce more output per hour on the job. But what if these same underlying technologies (big data, microsensors, ever-smaller computers) join forces in less obvious ways to revolutionize the way firms, and whole industries, operate? And, we ask, is the future actually as predictable as Gordon would have us believe? Legend holds that an 1876 internal memo from Western Union, the telegraph monopolist, read: “The telephone has too many shortcomings to be considered as a serious means of communication.” Well, we all saw how that turned out.

Bottom line: Rapid innovation – as Robert Solow might say – is everywhere except in the productivity statistics. So what gives? Macroeconomics may not have the answer. As Dr. Olivier Blanchard reminded us during our May 2016 Secular Forum, we macro folks actually know very little about productivity. So let us turn, instead, to microeconomics.

Microeconomics: a right-tail picture of global productivity

When we look at the state of industry in 2017 from the bottom up – sector trends down to company-level innovations – we see a global economy with underappreciated potential. A productivity-driven return to “old normal” 4%+ global GDP growth may lie within reach in the coming years, based only on the spread (“diffusion”) of existing technologies.

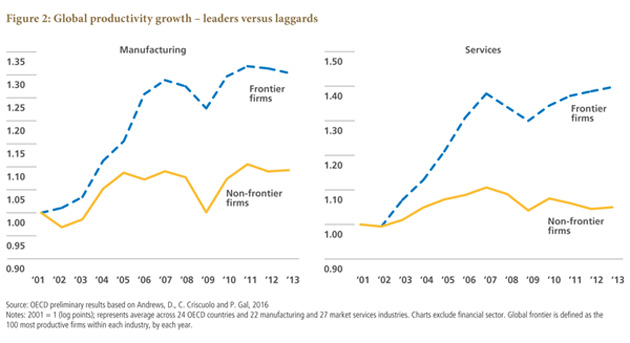

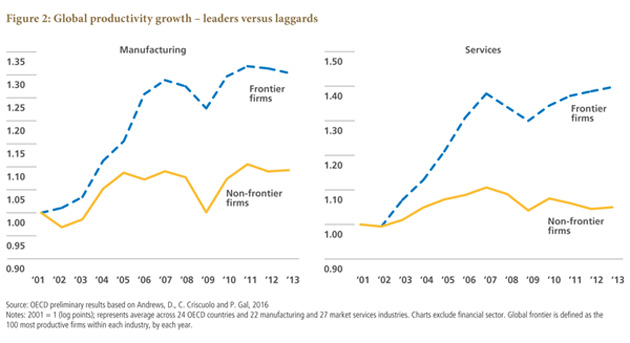

How? A handful of technologies have emerged that are radically changing the way firms do business. These technologies – offspring of the computer revolution – include artificial intelligence (advanced robotics), simulation, the cloud, additive manufacturing (3D printing), augmented reality, big data, microsensors and the “internet of things” (web connectivity of everyday objects). These technologies are now being used, in many cases for the first time, in synergy with one another. Together, they enable businesses to experiment more effectively, better measure their activities in real time, and scale their innovations – and those of their peers – faster. (See the works of Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee for more.) Here’s the key: Smarter experimentation plus faster scalability of winning ideas can speed up the diffusion of best practices from productivity leaders to laggards. And global “catch-up” potential is huge, especially in emerging markets (EM). The productivity gap between leading, “frontier” firms and all others has widened dramatically in recent years – see Figure 2. (Note: This gap does not merely reflect productivity differentials across industries.) The gap cannot widen forever; inefficient and unproductive firms can play defense for a while – creative destruction takes time – but eventually they will converge toward the frontier or exit. This growing divergence between leaders and laggards represents strong pent-up productivity gains waiting for a catalyst (… read on!).

So there’s potential for catch-up … but why now?

Two logical questions: Haven’t computers, the internet and automation been around for years? Why should we expect a productivity rebound anytime soon? One key reason: cost. Productivity-enhancing technologies exist today that haven’t yet been put to use because their cost outweighs their perceived economic benefits. That’s changing.

Case study: advanced robotics

Take robotics. Costs continue to fall while performance improves – making automation more and more competitive with human labor. In many industries, companies are nearing an inflection point where they can earn an attractive return on an investment in advanced robotics systems (Sirkin et al., Boston Consulting Group 2015). “Generic” robotics systems capable of many different types of work cost, today, about $28 per hour, already below the typical hourly human wage in a number of industries. By 2020, the cost of advanced robotics is expected to fall to $20 per hour or lower – below the average human worker’s wage. The Boston Consulting Group projects that growth in global installations of advanced robotics systems will accelerate from 2%–3% per year today to about 10% per year over the next decade. The result: robust productivity gains in the industries that can take advantage.

Sound fanciful? This isn’t the stuff of theory or hope. A major German shoe manufacturer, for example, is building its first factory on German soil in 30 years; the 50,000-square-foot facility will rely on robots and customized automation to slash logistics and supply-chain costs – and free up hundreds of factory workers to focus on higher-skill tasks. And the world’s two biggest airplane makers also are incorporating advanced robotics into their production processes. To date, both companies have built planes mostly by hand. But going forward, taking after the auto industry, they will use robots, drones and higher-skill human labor to boost production efficiency – a response to years of order backlogs and surging (unmet) demand. Why now? Because these technologies are now priced low enough that they become accretive to earnings – and therefore are poised to transform these companies’ business models (Wall 2016).

And now smaller firms are joining in. Until recently, advanced robotic systems were too complex and too expensive for small firms – but it now generally takes only a few months for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to earn a positive return on their investment in these technologies. Greater adoption by SMEs, most of which do not operate on the productivity frontier, will help speed up technological diffusion – a catalyst for faster aggregate productivity growth. (Note that SMEs account for about half of total employment in the United States.)

Pent-up productivity growth: examples from industry

Advanced robotics in shoe and airplane production is just the beginning. We may be approaching similar tipping points in other industries as well. McKinsey & Company, in a 2015 study authored by James Manyika and others, offered projections of global sector-level productivity growth potential through 2025 based on anticipated diffusion of known technologies and existing best practices. (Take the numbers themselves with a grain of salt; productivity trends are notoriously difficult to forecast.) Here are some of McKinsey’s industry-level estimates of potential annual productivity growth:

- Agriculture: 4%–5%. Big data and cutting-edge microsensors can team up to create “precision agriculture” techniques that improve real-time forecasting, production tracking and micro-optimization of irrigation and fertilization. The result? Rising crop and meat yields – and less waste.

- Automotive: 5%–6%. Big data, simulation and robotics can drive rapid improvements in operations – and force smaller manufacturers to merge, exit or adopt current best practices (the sector, globally, remains highly fragmented). Within parts supply, the industry’s largest segment by value added, advanced robotics may just be reaching the point of economic viability for second- and third-tier suppliers.

- Food processing: 3%. Mechanization and automation can drive robust productivity gains, mainly in EM countries where food and beverage production is still relatively labor-intensive.

What about notoriously low-productivity service industries? Boosting productivity growth in services will be critical given these sectors’ rising share of global employment. Here, we see new hope for productivity gains through catch-up, consolidation, or exit – mainly due to the huge productivity gap between leaders and laggards (as shown previously in Figure 2). But again we ask: Why now? Greater use of computers, web technologies and analytics (the stuff manufacturers adopted long ago) is opening up services to greater competition – both domestically and internationally through global trade. (As evidence, consider that across countries, the value-added share of domestic services in gross exports has been increasing at a faster and faster clip as services become increasingly tradable. The “micro-multinationals” are coming.) Bottom line: In services, productivity gains through basic IT and digitization may still be in their infancy .

Now for a couple of service sector examples from McKinsey’s 2015 study. Below are their industry-level estimates of potential annual global productivity growth through 2025:

- Healthcare: 2%–3%. Big data and simulation may produce gains through “smart” care, while basic IT improvements could drive time and cost savings. (Nurses, for instance, currently spend only one-third of their time on actual patient care. And imagine what happens when more doctors learn to use FaceTime for remote consultations.)

- Retail: 3%–4%. Global retail is ripe for creative destruction (consolidation, exit, or catch-up) given massive productivity gaps between retailers within countries and between retail sectors across countries (e.g., Japanese retail productivity is only about 40% of the U.S. level). The catalysts for change? In the McKinsey scenario, advanced analytics and big data will drive improvements in lean-store operations and supply-chain management. Competitive pressures are mounting, notably from the continued rise of e-commerce (80% more efficient than modern brick-and-mortar yet still only a small fraction of total retail activity – about 10% in the U.S.). “Modern” (i.e., large, as in not your local mom-and-pop) brick-and-mortar formats themselves are three times as productive as small, traditional stores – yet modern brick-and-mortar businesses are rare in much of the emerging world (where they represent a 25% – and often lower – share of total retail employment).

We could go on. Could government services, notoriously far behind the productivity frontier, be next in line for an upgrade? (For color, see Glaeser et al. 2016.) Evidence is trickling in that municipalities are turning to big data to better track their performance and provide public services more efficiently. And then there’s the education system ...

From micro gains to macro growth?

Could industry-level productivity gains boost global productivity growth in aggregate?

In our view, this (right-tail!) possibility is rising. And the microeconomic experts at McKinsey would seem to agree. In their 2015 report they draw from a collection of industry studies to project productivity growth through 2025 at the sector level – and then extrapolate these sector trends to global labor productivity growth in aggregate. McKinsey forecasts 4% potential annual productivity growth through 2025 – a jolt higher from the 2%–2.5% post-financial-crisis global average. (The forecast considers the G-19 countries plus Nigeria.) Note: This 4% forecast is based only on the diffusion of existing best practices and known technologies – i.e., before giving any credit to unknowable future innovations. As the study suggests, “Waves of innovation may, in reality, push the frontier far further than we can ascertain based on the current evidence.”

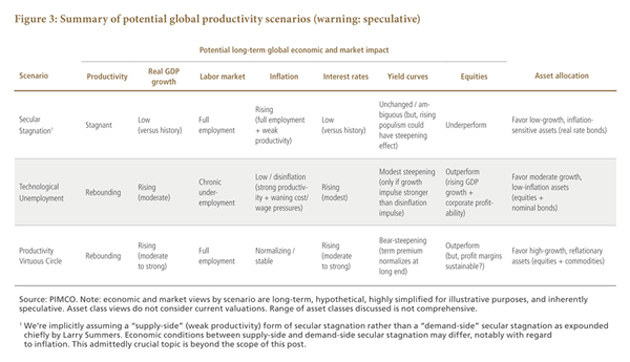

Three productivity scenarios and their investment implications

Broadly, we envision three possible scenarios for global productivity. The first is that our weak-productivity status quo – call it secular stagnation – persists. We all have a sense of what this paradigm means for economies and markets because we have been living through a version of it for years. The future effect of secular stagnation on interest rates is ambiguous – though we note that a continued global trend toward populism, absent a productivity rebound, could put a higher inflation term premium in nominal yield curves (causing curves to steepen).

The other two (more optimistic) scenarios both involve a productivity rebound; the resulting economic gains, however, manifest differently between them – and that’s because productivity growth can occur in two ways. Either innovation reduces required inputs for a given output (through efficiencies and cost savings), or innovation boosts output for a given input.

Productivity rebound scenario 1: ‘Technological Unemployment’

Under “Technological Unemployment,” innovation drives robust productivity growth through firm-level operational improvements and cost savings while chipping away at the demand for human labor. Productivity gains therefore come mostly from a reduction in (human) hours worked – mechanically, this is the denominator in the productivity calculation (output divided by total hours).

Consider the potential long-term economic and market impact of “Technological Unemployment” (note, we’re speculating and simplifying a lot here):

- Global GDP growth picks up moderately

- Inflation remains low and stable (a positive reflationary impulse from rising GDP growth is offset by a disinflationary impulse from falling costs and lack of wage pressure)

- Labor market distortions and inequality worsen; chronic underemployment develops (too many workers, not enough jobs)

- Global interest rates rise modestly from rock-bottom levels amid stronger economic growth (but disinflationary conditions limit the extent of the increase)

- Yield curves modestly steepen, but only if growth impulse more than offsets disinflation impulse; otherwise, curves could flatten

- Equity markets perform well given improving economic growth, muted inflation, and rising corporate profitability (falling costs and minimal wage pressure)

“Technological Unemployment,” in the extreme, is the scenario in which we humans are relegated to the beach while machines do all the work for us. The distribution of wealth across society could well become even more uneven given rising polarization between the “capital owners” and everyone else. This is a grim scenario for Main Street, and it would pose significant challenges – not only economic but also political and social.

Productivity rebound scenario 2: ‘Productivity Virtuous Circle’

Our “Productivity Virtuous Circle” scenario involves a different (and better!) type of productivity growth – one where innovation drives productivity gains without rendering human workers redundant. Here’s how. First, new technologies and processes employed in one industry generate cost savings and efficiencies in that industry. But they also create new jobs – jobs that require new skills we didn’t yet know we needed. A virtuous circle then develops: Technological growth in one industry forces related industries to innovate (or fall behind), creating even more demand for new skills. And on we go. The upshot: In this scenario there is no mass of discouraged (former) workers plodding off to the beach. Mechanically, productivity gains are driven mostly by a rising numerator (output) rather than by a falling denominator (hours worked).

Here is the potential long-term economic and market impact of “Productivity Virtuous Circle” (… still speculating):

- Global GDP growth approaches “old normal” levels (4%+) in an enduring escape from secular stagnation

- Inflation normalizes but remains well-contained (“demand-pull” inflation is offset by disinflationary impulse from positive productivity shock)

- Labor markets strengthen (full employment and solid wage growth)

- Global interest rates rise given strong economic growth

- Yield curves bear-steepen (term premium normalizes at the long end)

- Equity markets perform well given solid economic growth – but remain sensitive to the sustainability of profit margins (potential for labor to garner a larger share of the economic pie)

Clearly, in this scenario, bonds underperform in the short run (higher rates and steeper curves). But ultimately, we believe the “Productivity Virtuous Circle” would be the very best long-term outcome for fixed income investors.

We summarize the forces at play across all our scenarios in Figure 3.

What could go wrong? Barriers to diffusion

For the global economy to realize its full productivity potential under any rebound scenario, we need a lot to go right. While global industry leaders have enjoyed strong productivity gains in recent years, the median firm has not (recall Figure 2). The key to boosting aggregate productivity, therefore, is to speed up the diffusion of best practices from industry leaders to laggards. To maximize diffusion, governments need to continue to support free trade, a key enabler of global competition; liberalize product markets to enable the forces of creative destruction to do their work; make labor markets more flexible so that human capital will flow to its most productive uses; and help workers learn the skills required to best leverage tomorrow’s technologies. (Worthy topics for a future note …)

Bottom line: productivity’s upside risks are growing

So, what should we expect going forward? Secular stagnation or a productivity rebound? Our crystal ball isn’t that good. But whereas many market participants are coalescing around a secular stagnation baseline view, we are decidedly less convinced. In fact, we see a growing risk that we collectively underestimate the global economy’s pent-up productivity potential. It wouldn’t take a leap of faith to envision some variant of our “Technological Unemployment” productivity rebound (putting aside, in this note, its potentially serious social consequences). If future innovation displaces low-skill labor first, as we suspect it will, the impact on employment could indeed be negative – absent herculean worker-retraining efforts.

But don't count out a “Productivity Virtuous Circle,” which – lest we forget – is not lacking in historical precedent. The Luddites of 19th century England and their ilk have been wrong for two centuries; historically, over long periods of time, technological change has been a net creator of higher-skill jobs – and has not jeopardized full employment. (Over the past 50 years in particular, global labor productivity and employment have grown together in most multi-year periods.) Yet many observers seem certain this time will be different.

All told, we’d put better-than-coin-flip odds on a productivity rebound in some form in the coming years – and an escape from secular stagnation toward “old normal” global GDP growth. (The composition of GDP growth, however, will be skewed much more toward productivity gains than labor force growth.) The microeconomic catalysts have arrived. These catalysts – to recap, rising synergies in the use of leading technologies, declining costs, greater small-firm adoption and green shoots in services – may put 4% annual global productivity growth within reach. And that 4% includes zero credit for potential unknowable future innovations. (Yes, “unknowable unknowns” can be positive!)

There may also be a nascent macro catalyst at play. Global central banks are beginning to rein in extraordinary post-financial-crisis monetary stimulus, which – as our colleague Scott Mather suggests – probably has for years distorted the allocation of capital worldwide. The withdrawal of ultra-accommodative monetary policy may encourage a more efficient capital allocation throughout the global economy, potentially helping jumpstart creative destruction – the key to shrinking today’s massive productivity gaps.

Why, as investors, do we care? A productivity rebound could mean higher interest rates and steeper yield curves – greener pastures, indeed, for savers, pension funds and financial institutions. It could mean equity investors wouldn’t be doomed to a stagnant future of low returns. And it could boost the resilience of the global economy in the face of several looming secular risks. Productivity’s right tail is getting fatter; if history is any guide, the night often appears darkest just before dawn.

Closing Remarks from John

All of us might wish for a virtuous productivity cycle like the one they describe a scenario number two, and that is what has happened in the past. People left the farms and went to the cities to work in the factories and then moved on to other jobs. Technology created new jobs in the process of destroying past jobs. It was in the height of this process that Schumpeter wrote his famous “creative destructio” paper.

The problem with that scenario playing out in the future is that we literally had generations of time to adapt. If we had tried to go from 80% of the people working on farms in 1880 to 2% in 10 or 15 years – less than a generation – it would have been far more disruptive than the actual 20 generations it took. People had time to change.

I am far more concerned about today’s “technological unemployment.” Automated cars are just the tip of the iceberg. The Council of Economic Advisers thinks that 60% of lower-paying jobs will be automated in the next few decades. Where will these people go to work? Yes, we can retrain them for other work, but are they willing and able to be retrained? Will they be willing and able to move?

Given the nature of the change that I see coming, I think that income inequality will actually grow. In my upcoming book I will put a mathematical formula to it and demonstrate that in the future income inequality will be worse, no matter how you cut it. And increased taxes are going to slow down growth and reduce employment opportunities. There are no free lunches.

Add that in the coming debt crisis, the inevitable demographic changes and geopolitical tensions are going to contribute to the slowing of GDP growth. All of which makes it difficult to be a pure technological optimist. I mean, yes, we’re moving toward a world of abundance and marvelous new technologies, but like the past, the future will be unevenly distributed for quite some time.

And that does not even get into the issue that the way we measure GDP is so fundamentally flawed as to produce statistics that are essentially misleading. Seriously, to an economist, a $100 barrel of oil or two $50 barrels of oil have the exact same GDP impact. Ask a kindergarten child which is better, one cookie or two cookies? Just saying…

I will close here, but you get the thrust of what I’m trying to cover in the new book. I think that Matt and Joachim did a fabulous job in taking us on a thought trip and making us question our assumptions.

Mr

Mr