Japan's Well-Fed Zombie Corporations

The corona crisis has intensified the discussion about the zombification of the economy; enterprises have become more dependent on government bailouts, loans, subsidies, short-time working benefits, and loans from central banks. Governments around the world claim the measures to be only temporary. Yet Japan’s experience suggests that the reliance of enterprises on public support can continue in one form or another. Japan’s enterprises have long relied on the state and more so during the corona crisis, a path that the US and Europe seem to be following.

There is no formal definition of zombie enterprises. Investopedia defines an enterprise as zombie if it earns just enough to keep operating and to service its interest but is unable to pay off the interest or to invest. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study views a zombie as a firm that cannot cover its interest payments with profits for several years (Adalet McGowan et al. 2017). Caballero, Hoshi, and Kashyab (2008) pay attention to the role of banks, which extend financing to otherwise insolvent borrowers at the expense of profitable firms. Such a lenient practice of extending loans to distressed borrowers is also referred to as forbearance lending (Sekine et al. 2003).

Seen through the lens of Adalet McGowan et al. (2017), the number of zombie firms decreases if central banks gradually lower interest rates. Yet, the number of zombie firms is supposed to increase when central banks ease financing conditions such that enterprises with weak profitability are kept alive. If the loose monetary policy is perpetuated, the efforts of enterprises to increase efficiency and innovate diminish (Leibenstein 1966). Enterprises are "evergreen" (Peek and Rosengreen 2005), while aggregate productivity gains and real growth decline. The high stock of (potentially) nonperforming loans lies with zombie banks, which survive because the government provides explicit or—through persistently loose monetary policy—implicit guarantees (Schnabl 2015).

Zombification in Japan begins with the bursting of the Japanese bubble in December 1989. In the second half of the 1980s, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) had fueled a stock and real estate bubble through sharp interest rate cuts. When the bubble burst, bad loans piled up on banks' balance sheets. The Bank of Japan cut interest rates toward zero in an attempt to insulate the economy from the ravages of bad loans. This plan had seemed to work, with outflows of Japanese cheap money toward Southeast Asia; yet the plan failed with the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis, which triggered the Japanese financial crisis in 1998. The stock of (potentially) bad loans further grew.

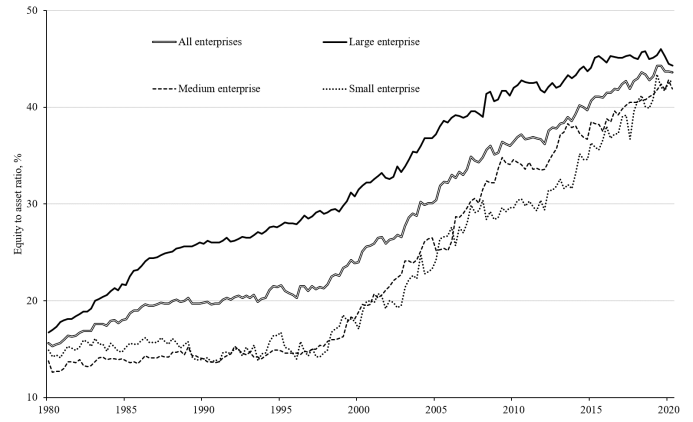

Japan: Equity-to-Asset Ratio by Enterprise Size

Source: Ministry of Finance, Japan. The equity-to-asset ratio is defined as the equity divided by the total assets.

The increasing leniency came from politicians. Members of the legislature from all regions of the country feared the anger of their voters in the event of bankruptcies. Because the persistently loose monetary policy kept reducing the banks' net interest revenues, the distressed banks were destabilized further (Schnabl 2020). The Japanese banks hesitated to sufficiently price default risks and to close weak companies' credit lines, because the risk of additional nonperforming loans seemed too high.

The lenient bank lending policies were supported by the government, which softened corporate lending requirements through numerous pieces of legislation. Many small and medium-sized enterprises received public loan guarantees in the course of the 1998 and 2008 crises. The Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Financing Facilitation Law in 2009, for example, gave banks the incentive to grant very generous credit facilities and extensions to small and medium-sized enterprises. Enterprises just had to submit a business plan that promised an improvement in their situations. Many loans that were actually nonperforming were reclassified as healthy loans. In 2012, further measures, such as deferrals, ensured that the credit burden of small and medium-sized enterprises at risk of default was kept bearable.

The upshot is that the brakes were put on restructuring enterprises. Economic growth was paralyzed, business expectations remained negative, and domestic sales stagnated. However, corporate profits tended to remain stable, because the Bank of Japan decreased the interest expenses of enterprises and the never-ending crisis led to restrained wage demands. The average wage increase of large enterprises through the so-called Shuntô wage negotiations remained stuck at nearly 2 percent after 1998, in contrast to 9 percent on average from 1956 to 1997. The real wage level has been decreasing since 1998 (Latsos 2019).

Despite stable corporate profits, however, Japanese companies did not invest. Sitting idle on the liquidity, they repaid loans and expanded equity (see chart). The corporate sector changed from a net borrower to a net saver. Small and medium-sized enterprises are holding their retained earnings mainly in the form of bank deposits. Large enterprises invest in the international expansion of their business activities, in particular in the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as well as the establishment of foreign branches. The equity-to-asset ratio of Japanese enterprises increased, because corporate profits failed to recirculate into the Japanese real economy.

The ever-increasing equity ratios of Japanese companies can thus be seen as the outcome of subsidization by the government, by the Bank of Japan, by commercial banks, and by households (employees). Many companies are in economic distress due to the never-ending stagnation but survive thanks to comprehensive aid. The corporate sector as a whole is zombified, despite a high equity ratio, because it does not invest in market adjustments and relies on government aid and restrained wage demands by workers. As the falling wage levels since 1998 depress consumption demand, it would be irrational to invest in larger capacity. The survival of enterprises increasingly depends not on their efficiency, but on the low interest rate environment created by the Bank of Japan: enterprises need to generate just enough profits for survival and for a gradual reduction of liabilities, which turns into a gradual increase of the equity ratio—a corollary of zombification.

It is thus the Bank of Japan that can pave the way out of the zombie economy. If the Bank of Japan slowly raised the key interest rate, the government would reconsider costly lenient legislation and enterprises without a business model would have to exit the market. To remain in the market, they would have to invest in efficiency gains and innovation. The exceptionally high equity ratios would decline. The resulting productivity gains would allow for wage increases, which would strengthen consumer demand and growth. Investment would become worthwhile again, and the living dead would be reanimated. The once proud Japanese economy could rise like a phoenix from the ashes.

Britain’s recovery is threatened by the growing savings glut

Saving for a rainy day may seem prudent but can do an awful lot of damage when embraced by all at once