Europe must slash red tape if it wants its moment in the sun

Spain’s economy is shining and the Continent is wooing investors fleeing the US. But for this to be a true turning point, we need a bold regulatory reappraisal

With full hotels, busy shopping centres and bustling restaurants, my trip to meet investors in Madrid last week felt more buoyant on the streets than any other visit to Spain I’ve made in the past decade.

The Spanish economy is the fastest growing in Europe, and during my week-long trip to the capital, there was a tangible sense of consumer confidence. The country’s new-found mojo reflects Europe’s recent “glow-up”, which has been given greater momentum by investors taking fright at the US administration’s scorched-earth approach to international trade and diplomacy.

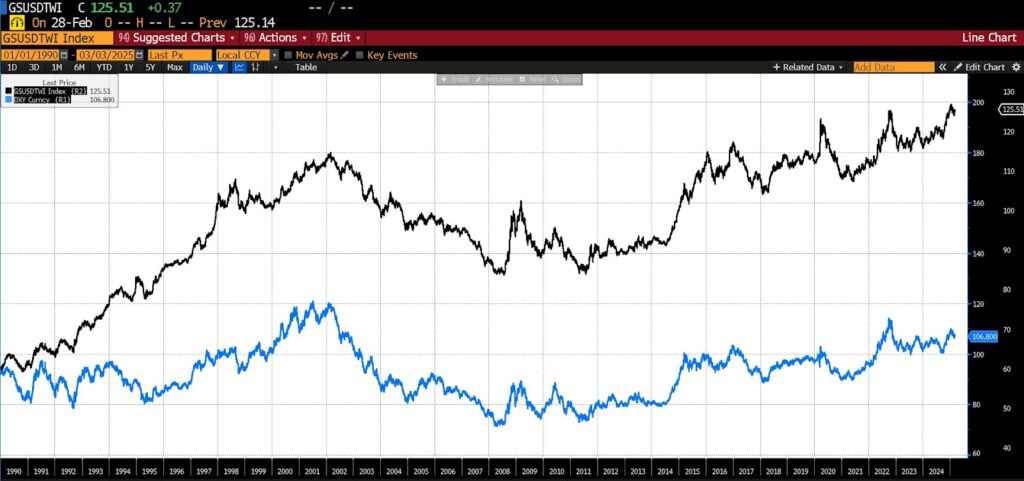

According to the data firm Morningstar Direct, European exchange-traded funds have enjoyed an 18 per cent jump in inflows. With President Trump’s efforts to Make America Great Again having the opposite effect on domestic stocks, Europe appears to be the main beneficiary of capital leaving the US.

• Booming Spain is on track to a new age of prosperity

With this and Spain’s hot growth streak in mind, you might have thought the investors I met in Madrid would be especially bullish. But this wasn’t the case. The sense of economic optimism I detected on the streets didn’t extend to the meeting rooms of the city’s financial district.

It wasn’t that the investors I spoke to were entirely downbeat. They acknowledged there had been a “vibe shift” in European markets, and Germany’s scrapping of the “debt brake” — its longstanding, Scrooge-like rules on government borrowing — was hailed as highly significant. The rationale for this reform is to fund a massive increase in defence spending, but it’s assumed that the ripple effect across both Germany itself and Europe as a whole will extend far beyond tanks, planes and cybersecurity.

Investors are betting on a substantial increase in public investment, and particularly an overhaul of Germany’s creaking public infrastructure.

• Merz wins vote to ditch decades of German caution and rearm

Yet the consensus was that easing the debt brake, even with the mammoth investment it will unlock, isn’t enough to Make Europe Great Again over the long term. True growth needs accompanying reforms to Europe’s over-burdensome regulation.

Between 2019 and 2024, the EU produced 13,942 legal acts, while the US produced just 3,725 pieces of legislation and passed 2,202 resolutions. The Madrid-based investors I spoke to fret that German fiscal stimulus will be ineffective at breathing new life into Europe’s ailing economy because it is simultaneously being strangled by red tape. Given Donald Trump’s zeal for deregulation, the transatlantic divide in bureaucracy will only widen.

Parts of the EU’s statute book read as though they were dreamt up by a whimsical toddler — such as the laws governing the curvature of bananas and cucumbers. These oddities may be fairly innocuous in themselves but speak to an endemic and economically unhealthy obsession with rules. When this is applied to labour laws or the burdens placed on the Continent’s banks, which constrict their ability to lend, investors really begin to despair.

Germany has a particular issue with sick days, with the average worker there taking 15 days a year, almost double the US average of eight and (a little surprisingly) three times the UK average of five. You don’t need to be Elon Musk to see the issue here.

The EU’s stringent capital requirements for its banks (known as CRD IV) are generally loathed by investors and blamed for limiting lending to small businesses and stymieing innovation. Critics point out that the US has about 550 more “unicorns” — start-up companies valued at more than $1 billion — than the entire EU, and that, as of last week, European stocks trade at 17 times earnings, compared with the US’s multiple of 26.

Last year Mario Draghi, the former Italian prime minister and European Central Bank president, wrote a 400-page tome of recommendations to boost the EU’s moribund growth, with deregulation as a key component. Most dismissed it as a pipe dream, with European countries seen as too stuck in their ways.

Germany’s recent constitutional reforms would have been considered unthinkable at the time, but the result of them is that investors are now piling into European companies. For this to be a true turning point rather than just short-term respite — as the investors I met in Madrid feared — the radical fiscal rethinking we are seeing in Europe needs to be matched with an equally bold regulatory reappraisal.

Seema Shah is chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management