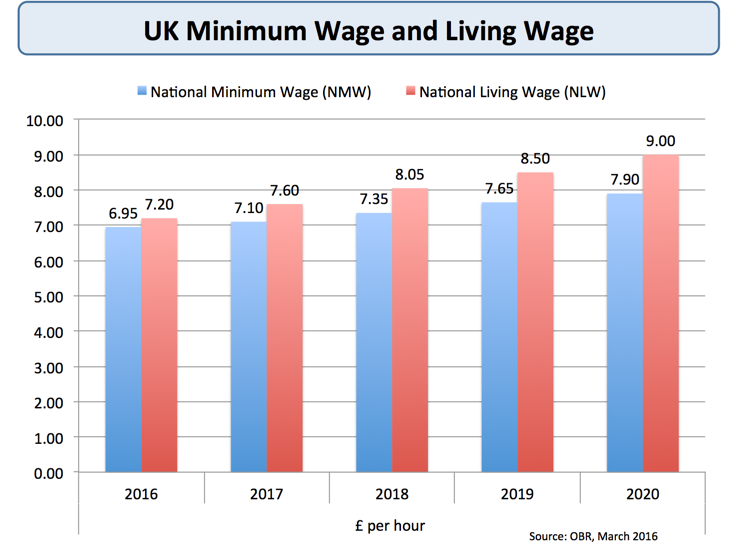

The new remit of the Low Pay Commission (LPC) asks them to recommend the future path of the NLW, with a target of the total wage reaching 60% of median earnings by 2020. On Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts, a full-time NMW worker will earn over £4,800 more by 2020 from the NLW in cash terms

Many firms, particularly those in traditionally low-wage sectors such as pubs, restaurants and social care, have expressed concerns about the impact of this significant rise in labour costs. But while recent research finds that the stock market value of companies likely to be constrained by the NLW fell when the policy was first announced, the reduction was nowhere near big enough to suggest anything other than temporary problems. Nevertheless, the employment effects of minimum wages have long been disputed by economic researchers.

Many economists who disagree that the NLW would lower employment stress that it only covers a small fraction of the labour force, so it is unlikely to have a significant effect on aggregate unemployment.

Michael McMahon (Warwick) argues that ‘the total number of employees earning the minimum wage is a relatively small proportion of total employment’.

Andrew Mountford (Royal Holloway) argues that ‘if the National Living Wage causes firms to invest in the productivity of their workforce and workers to invest in themselves, then it will have a significantly positive effect on UK economic performance in the longer run.’

However Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford) comments that ‘I suspect that it will lead to significant reductions in employment in the residential care sector, because here the scope for squeezing profits is small and the government partly fixes the price.’

Morten Ravn (University College London) is concerned about distributional effects and believes that ‘it would seem rather fairytale-like to believe that a large increase in wages at the bottom of the distribution could be implemented at no cost of employment of the workers concerned.’

Andrew Mountford (Royal Holloway) argues that ‘if the National Living Wage causes firms to invest in the productivity of their workforce and workers to invest in themselves, then it will have a significantly positive effect on UK economic performance in the longer run.’

However Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford) comments that ‘I suspect that it will lead to significant reductions in employment in the residential care sector, because here the scope for squeezing profits is small and the government partly fixes the price.’

Morten Ravn (University College London) is concerned about distributional effects and believes that ‘it would seem rather fairytale-like to believe that a large increase in wages at the bottom of the distribution could be implemented at no cost of employment of the workers concerned.’

Will the new national living wage lead to a surge in wage inflation and consumer prices?

The Economics Nobel prize-winner Christopher Pissarides (LSE) argues: ‘the main effect will be on prices but given the number of workers on the minimum wage and the overall share of labour in costs the impact will be muted.’

Jonathan Portes (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) points out that while the aggregate effect on wages and prices may be small, ‘It will have a significant impact on wages for some workers and hence some companies.’

Jagjit Chadha (Kent) states that ‘In order to maintain relativities, firms may reduce both overall labour hours or total employment numbers and the increase in the wage bill may drive up firms’ costs, which may increase the overall price level and lead to temporarily higher inflation.’

The strongest opposition to the NLW is expressed by Patrick Minford, who argues that ‘with such a large rise in low-paid wages, there will be effects right up the wage scale… This will also put upward pressure on prices.’

Michael McMahon (Warwick) echoes the views of some participants that ‘some small upward pressure on inflation is potentially to be welcomed, given how close to deflation we are at a time that interest rates are already low.’

Michael McMahon (Warwick) echoes the views of some participants that ‘some small upward pressure on inflation is potentially to be welcomed, given how close to deflation we are at a time that interest rates are already low.’

Chris Martin (Bath) takes this further by suggesting that the NLW might get the UK out of what he sees as a low-wage/low-pay trap, because ‘raising the cost of labour gives more incentive for firms to invest in skills, an area where the UK is chronically weak at the bottom end of the wage distribution.’

The key unknown for many participants is how quickly the UK economy will grow in the coming years.

The key unknown for many participants is how quickly the UK economy will grow in the coming years.

Putting both sides of the argument, Wouter Den Haan (LSE) writes that ‘If the UK economy grows rapidly, then the increase in the NLW is unlikely to matter much for anything except low-wage workers. If the UK economy does not grow rapidly, then the increase in the NLW could have an impact on employment, but inflationary pressure is unlikely in such an environment.’

No comments:

Post a Comment