More in my bid to get you prepared to spice up your essays; this is an extract from a Mauldin newsletter, and I've highlighted the bits that you could use if you get a question about spending, and you are stuck for a way to say how to generate the revenue (NB this applies to ALL spending, transfers, current & investment). If you want to read the whole thing you'll have to ask me to forward you the email (I won't hold my breath). As usual, this is very US-centric, but broadly it applies here. Let's start with income taxes - not much meat here:

[And now the points behind this:]

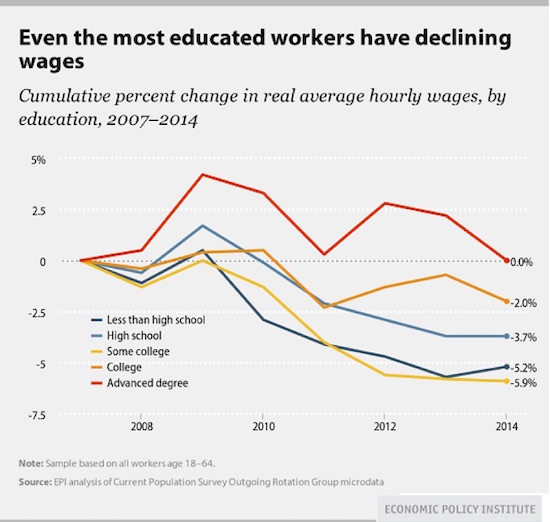

"And while incomes have stagnated, the real cost of goods and services has increased much more than the purported inflation rate suggests. The cost of housing, utilities, and local taxes has certainly increased beyond inflation levels. And don’t even get me started on how much has gone up, crushing families who can least afford it.

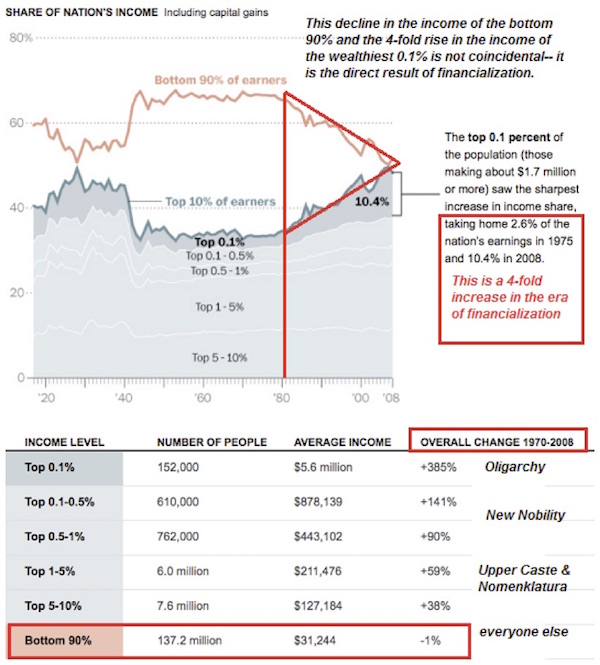

This next chart paints our economic situation in even starker terms. The bottom 90% of Americans have seen their overall income drop. Low interest rates and quantitative easing have dramatically helped the top 10%, and we could break out the numbers to show that it’s actually the top 25% that have benefited, though the further down the income chain you go, the less the Fed’s tinkering has helped. The financialization of America is directly responsible for this turn of events, and rather than helping GDP growth as it was intended to do, it has thwarted growth.

You need to do something, something radical, to shake up the system, to make sure those at the bottom get an increase in income all the while making sure that you don’t push the economy, which is already stalling, into a dive. Economics and politics as usual simply will not cut it.

Giving Everybody Some of What They Want…

But Not Everything They Want

Here is the basic political reality you’re dealing with. Republicans want supply-side tax cuts and flat taxes, spending cuts, and a balanced budget, or some combination of all of them. Democrats want more spending for healthcare and other consumer-related items, an agenda that means higher taxes; and many, if not most, would at least give a nod to balancing the budget. Everyone is for “the little guy.”

So let’s start with the easy part. You’re going to want the Republicans to go along with an increase in the total tax revenue. If you forget for a moment where you want to extract that revenue from (by taxing the rich, for instance) and just say that your goal is to get more tax revenue, then you will have a lot more flexibility. And the reality is that you could significantly raise taxes on the rich (and by “the rich” I mean the top 20% in income) and still get nothing close to the amount you need. The sad reality is that you would have to raise taxes not only on the rich but on the middle class in order to make a difference. And I’m going to assume that raising taxes on the beleaguered and shrinking middle class is a nonstarter for pretty much everyone.

So to get what you want, give the Republicans a tax cut that will get every one of their little supply-side hearts absolutely quivering in anticipation. Give them so much of what they want that it becomes almost impossible for them to say no. That means you can’t be halfhearted; you’re going to have to go the whole hog.

[this bit is controversial - I like it, but I don't expect you to buy into it:] Offer a 20% flat tax on income over $100,000. Period. No deductions for anything. Dividends, interest income, municipal income tax revenues, all are taxed at 20% above the total $100,000 income level. Every sacred cow goes. No mortgage deductions, no charitable contribution deductions, no child tax credit, no nothing. Every penny over $100,000 is taxed at 20%. Now, you can make an argument that income from say $50,000–$100,000 should be taxed at 10%, but that’s not going to give you enough money to do what you need to do in order to be able to get the support of the Democrats. There is, on the other hand, a case to be made that people making over $50,000 should contribute something to the overall general welfare of the economy.

That still gives everyone up and down the ladder a major tax cut. There is not a supply sider in America who is not going to like that tax structure. Your income tax filing is done on a 3”x5” card. If you made between $50,000 and $100,000, you pay 10%. If you made more than that, you pay $10,000 plus 20% of everything you made above $100,000. This is going to be surprisingly popular with millennials: survey after survey shows that one of their big fears is dealing with the IRS. In a world where 40% of America is now getting some form of non-salaried income, dealing with the IRS is becoming more complicated. Millennials are increasingly part of the gig economy, and a flat tax will make their lives easier. You are going to be surprised at the level of support this tax proposal will get from young people.

Now, this tax structure is, of course, going to make people who want to soak the rich unhappy, as they don’t see how the little guy benefits. So here is where we have to get really creative. And this is why you are giving the Republicans something that’s going to be very difficult for them to walk away from: you’re going to combine their tax cut with two additional items.

To the Democrats, offer to abolish the Social Security tax on both sides of the equation, both business and personal. That means an individual making $30,000 a year gets an approximately $2000 pay raise immediately. Every working man and woman gets a pay increase in the form of no deductions for Social Security taxes from their wages.

So where do you get the money? You’re certainly not going to get the support of senior citizens or anyone else for that matter if you start messing around with the ability to pay Social Security benefits. So that means we have to find another revenue source.

[and here is the main bit you can use:]

And for that revenue source you need to turn to the tax that is the most efficient in economic terms: a consumption tax. But not one that looks like a sales tax. Rather, it should be a version of what almost every other country in the world uses, and that is a value-added tax, or VAT. I would modify it to look more like a business transfer tax (BTT).

Basically, with a BTT, a company pays tax on the revenue it receives net of what it pays for the services and products it is selling. Netflix pays on the revenue it receives after deducting the money it sends to television and movie producers for the rights to show their products. This is all transparent to the end user.

You can tinker around the margins to make this tax more politically acceptable. You can exempt groceries, but then you’re going to have to charge a higher rate on everything else. You can exempt nonprofits, but I wouldn’t: they pay Social Security tax on their employees now. But that may be the price of getting the deal done.

A BTT in the low teens (12-14%) will get you all the revenue that you need. You look the Republicans square in the eye and say I want to get 2% of GDP more tax revenue in the form of the BTT in return for the income flat tax on individuals. By the way, the BTT is legally deductible by US corporations under WTO rules when they ship products overseas – which is what every other country does to us, and why they have a tax advantage over us when shipping products to us. The BTT is going to be a huge boon to US producers. Talk about a cheap way to boost the economy – this is it.