Key points highlighted, all useful at some point in a trade essay:

More buyers wanted

Exports continue to disappoint, even in sectors where Britain should do well

The shipping forecast: gloomy

The shipping forecast: gloomy

THE prime minister summed up Britain’s trade dilemma when he said last year: “We’re still selling more to Hungary than to Indonesia—even though Indonesia’s population is 25 times bigger. We still do more trade with Belgium than we do with Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam combined.” At which point David Cameron got on a plane, accompanied by a delegation of businessfolk, and jetted off to South-East Asia to try to do something about this glaring imbalance.

Plenty of ministers have been criss-crossing the world during the course of Mr Cameron’s governments with the same aim in mind. Mr Cameron himself has been to India three times. The government has been banqueting the likes of China’s president and India’s prime minister in London, all to improve trade. Yet for all the ministerial airmiles and silver goblets, the country’s exports have remained fairly flat, and have been getting worse since 2012, certainly compared with those of the other big rich economies in the G7. The value of Britain’s exports fell by 1.5% in 2014 from 2013—the only G7 country where exports dropped—and last year’s figures were hardly inspiring, with a 1.5% fall in the three months to November compared with a year earlier. “It has been a disappointment, especially after the devaluation of sterling in 2008-09,” says John Van Reenen, head of the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics (LSE).

Sterling fell by 15% against the euro and 24% against the dollar during the 2008 financial crisis, and this did help exports in the short term. But since 2012 Britain has been struggling, even in the sectors it usually does well in. Thus the government’s hopes of recapturing some of Britain’s past trading glories and doubling exports in goods and services to £1 trillion ($1.5 trillion) by 2020 will remain exactly that. These trends also have ramifications for the argument raging over whether Britain should leave the European Union.

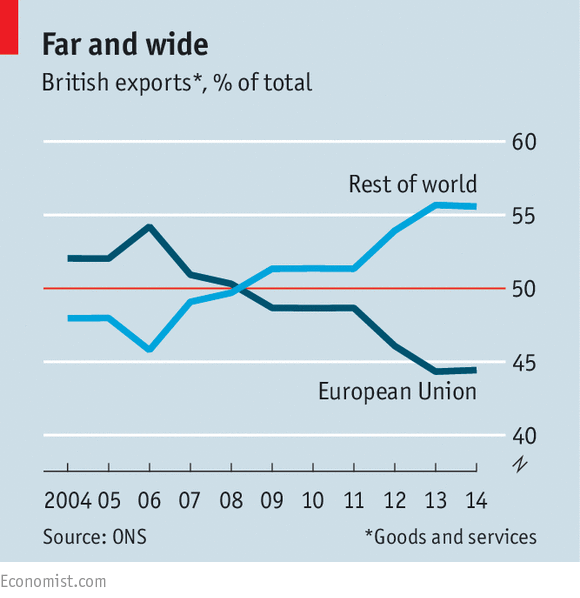

On the positive side, at least one rebalancing has been relatively successful. Britain’s trade with the rest of the world has been ahead of its trade with the EU since 2008 (see chart). To Eurosceptics, this is evidence that Britain could flourish outside Europe. But although Britain’s exporters have been getting a foothold in the emerging markets, they have not been as successful as they might have been. With the exception of China, which takes about 5% of Britain’s exports, trade in goods and services remains pedestrian.

For although nobody expected Britain, where manufacturing has shrunk to around one-tenth of GDP, to export many manufactured goods to emerging markets in the way that Germany does, the country was predicted to do much better in services such as banking, accountancy and education. This is where Britain has its main competitive advantages, such as the English language. Its trade in services with the EU has been growing at just over twice the rate of EU growth, but elsewhere the picture is less rosy. Although Britain’s services trade with emerging economies rose fast in 1998-2012, as the Centre for European Reform, a think-tank, points out, only in the case of Brazil did Britain’s exports “grow significantly faster than the economy concerned”.

Thus, as Paul Hollingworth of Capital Economics, a consultancy, argues, Britain has not been gaining market share in emerging economies. Indeed, its exports of services probably slowed in 2014 compared with 2013. Partly for this reason, trade with big countries like India remains small, and minuscule in the case of populous, fast-growing (if poor and distant) Indonesia. It has become a mantra among boosters of British trade to India and other emerging markets that as they become richer so they will need more of Britain’s bankers and fewer of Germany’s machine-tools. But, warns Swati Dhingra, a trade economist at the LSE, there is little evidence to support that theory so far. India, for instance, is not much in need of British expertise in business services, in which it has already developed its own industry.

There are other reasons for what the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) has called this “missed opportunity” in emerging markets, aside from the strengthening pound. Simon Walker, the head of the Institute of Directors, another big business-association, fingers the government’s lacklustre support for exporters on the ground, despite all the ministerial jet-setting. “Britain is bad at focusing on specific business opportunities and identifying market gaps, especially in less sexy areas,” he says, adding that France and Germany do this much better. Rather feebly, British exporters struggle with language and culture outside the Anglosphere, according to surveys by the BCC of its members; it argues that too many mid-sized companies, in particular, have no ambition to export.

Then there is the question of red tape and access to markets. Trying to satisfy all 28 of its members means that the EU often takes years to negotiate free-trade agreements; Eurosceptics argue that if Britain were unencumbered by the lumbering EU it would more easily cut its own bilateral deals with countries and boost trade. But economists warn that Britain’s bargaining position would be so much reduced on its own that it would be hard to get any very beneficial deals. And as Ms Dhingra points out, it is Britain itself that has contributed to holding up the India-EU free-trade deal, on the issue of immigration.

Exporters will get a short-term boost in the immediate future as sterling has weakened over the past weeks. But recent history suggests that in the longer term there are no shortcuts to boosting exports—it’s just more of the old slog of flogging a product that people want at the right price.

No comments:

Post a Comment