March 6, 2017

The State of US State Exports

By George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

A domestic political battle is brewing in the United States between President Donald Trump’s administration and the Republican Party over the president’s economic plans. Trump’s key economic positions during his campaign included his opposition to free trade deals, his promise not to cut Social Security and Medicare, and his support of large-scale infrastructure spending. These are all positions that have clashed with general Republican orthodoxy. They were also the reason that some Bernie Sanders supporters found themselves nodding in unexpected agreement with Trump’s proposed policies.

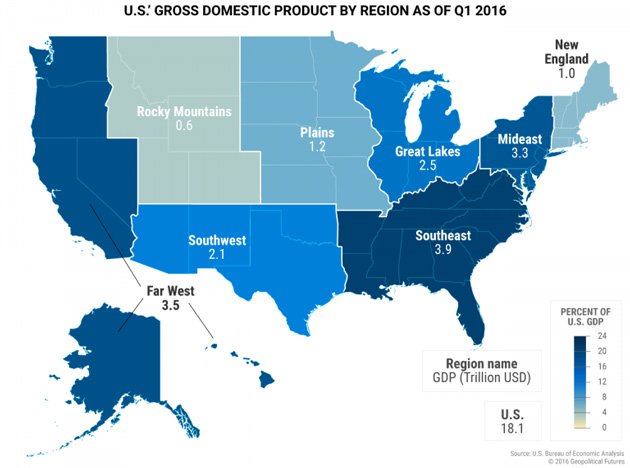

We can bring one key insight to this conversation as the battle lines are being drawn. It is extremely difficult to speak of the US economy as an undifferentiated whole. The US has varied economic interests at both the regional and state levels. This makes it extremely difficult to find a one-size-fits-all policy that can fix every problem.

This is not only true for the US—almost all large countries (and even some small ones) are highly regionalized. It is also not to say that national economic statistics are useless—they can be used to make important observations about the overall performance of a national economy, especially in terms of the economic power of a given country. But too often, discussion of the US economy focuses disproportionately on the national level and not enough on the regional.

What Export Patterns Tell Us

One way to illustrate how regions differ from each other is to look deeper at US exports. Readers of Geopolitical Futures’ work will be familiar with this concept: the US is the largest economy in the world by far, and yet exports account for just 12.6% of US GDP.

In absolute terms, US exports are still worth more than in most countries, totaling $2.2 trillion in 2016, according to the US Census Bureau. The only other country that comes close to or surpasses the US in terms of export value is China. The latest World Bank figures put the total value of Chinese exports at $2.4 trillion.

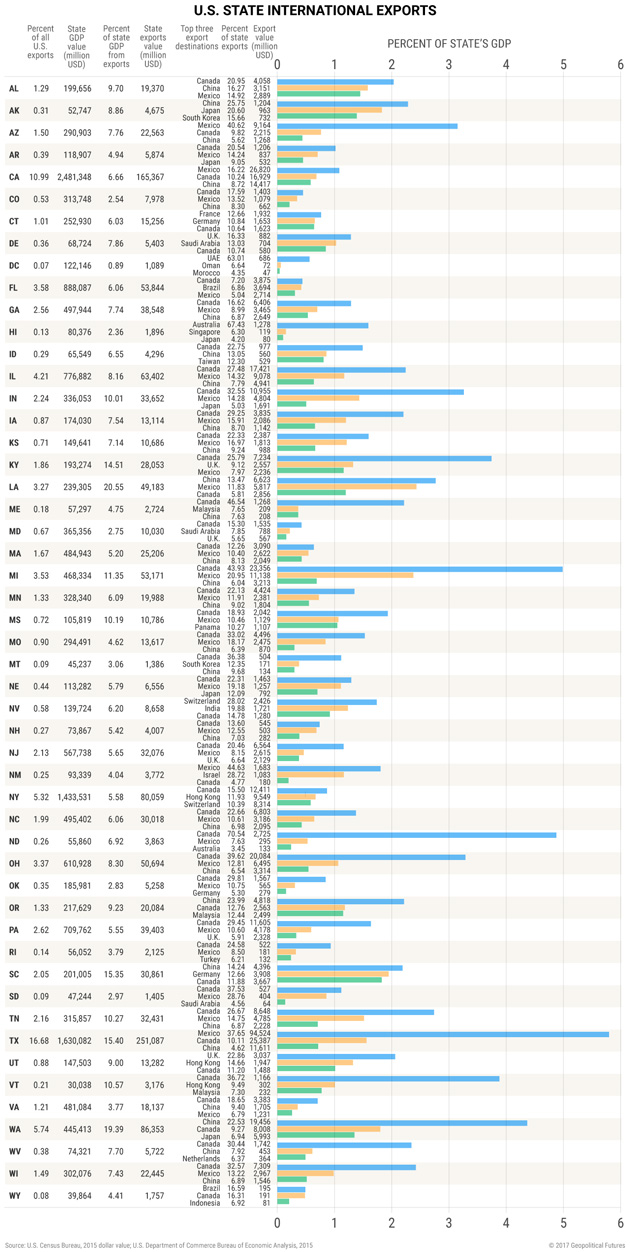

But on the whole, the US is a massive consumer economy that is not highly dependent on exports. This is true at the national level, but when US trade statistics are broken down by state, the situation is more complex.

Only 10 US states derive more than 10% of their state GDP from exports: Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. Eight of these states are located either in the Mideast or the South and voted for Trump in November’s presidential election.

Of these 10 states, four derive more than 4% of their GDP from exports to just one country. Michigan and North Dakota are highly dependent on exports to Canada. Texas is inordinately dependent on exports to Mexico, and Washington is heavily reliant on exports to China.

Views on NAFTA and China

Each state’s approach to trade agreements and negotiations will be defined by its own trading practices and economic focus. For states like Texas and Michigan, NAFTA is going to be a major economic and political issue. A large portion of these states’ economies—and a significant number of jobs—relies on trade across their southern and northern borders, respectively. These states also view the rise in China’s share of global manufacturing production as a potential threat, since they are manufacturing centers and China can produce goods at lower costs.

On the other hand, a state like Washington, located on the Pacific coast, will be less concerned with NAFTA and more concerned with policies that would open new potential trading markets in Asia. For example, stricter trade policies with China could affect Washington’s access to the Chinese market. As such, Pacific-facing states will have different priorities than Atlantic-facing states… and these regions will have different interests than the heartland.

Even states with similarly sized economies can have vastly different approaches to trade and economic policy based on their specific economic activities. Take South Carolina and Connecticut as examples. These states have similar GDP totals. However, as a percent of total US exports, South Carolina exports twice as much as Connecticut. In Connecticut, exports account for about 6% of GDP, and the state’s top trading partner is France. In South Carolina, exports account for over 15% of GDP, and the state’s top trading partner is China.

South Carolina is a manufacturing state and has been affected by globalization in a much different way than Connecticut. Ironically, a study by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University ranks Connecticut dead last in terms of fiscal solvency of all US states, whereas South Carolina is ranked 18th. But such statistics observe dependencies each state develops and, therefore, speak to the individual states’ policy priorities.

A Lesson for Washington

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, for a policymaker in Washington, DC to design a plan that will benefit both South Carolina’s manufacturing industry and Connecticut’s financial services and insurance industry. And these are just two of 50 states. Any federal official attempting to make plans at the national level must think in terms of 50 different states, or eight different economic regions, or a number of other divisions that reveal shared interests.

The map below indicates the vast differences between regions just in terms of GDP.

This is not a novel observation. The US Civil War was fought, in part, because different systems of economic production in the North and South created not just economic fissures, but also social and cultural gulfs so great that the country went to war. Earlier still in US history, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson lived in different economic universes, and the arguments between Federalists and Jeffersonian Democrats (and their views on economic policy) shaped and continue to shape the US’s development. The fault lines may have shifted, but the fundamental issue—the relationship between the federal government and the individual states—has never been settled.

The coming battle over economic policy will feature much grandstanding and sincere promises, some of which may be fulfilled. To understand what is at stake and why certain politicians advocate certain positions, it is not necessary to parse tweets or examine individual ideology. At the international level, we always argue that imperatives and constraints shape individual leaders as well as state actors. This is just as true at the subnational level, and even more so in a republic like the United States, where representatives who do not act in the interests of their constituencies can quickly find themselves out of a job.

George Friedman Editor, This Week in Geopolitics |

Quote of the day

“I find economics increasingly satisfactory, and I think I am rather good at it.”– John Maynard Keynes

Tuesday, 7 March 2017

Great article on US Trade current & outlook:

Great article looking at Trump's plans and reality. Really useful essay material:

Labels:

China,

exports,

free trade,

imports,

protectionism,

trade,

trade agreement,

US

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment