John Mauldin | Apr 26, 2017

Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook, Q1 2017

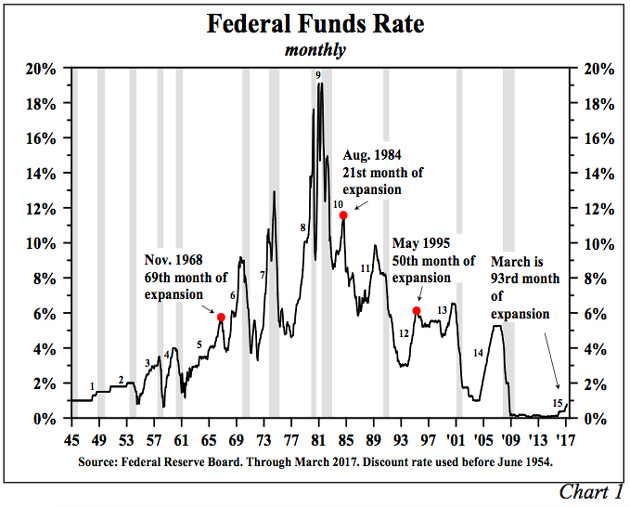

Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington kick off their Q1 “Review and Outlook” – today’s Outside the Box – with a bang, calling our attention to the fact that in 80% of the 14 Federal Reserve tightening cycles since 1945, a recession ensued, and the Fed managed to keep the Good Ship Economy off the rocks just three times.

And, oops, we’re in the 93rd month of the current expansion, farther out to sea than we were those three times when the Fed brought us safely in to port, in 1968, 1984, and 1995.

It gets scarier:

[T]he last ten cycles of tightening all triggered financial crises. In conjunction with the non-monetary determinants of economic activity (referred to as initial conditions), monetary restraint served to expose over-leveraged parties and, in turn, financial crises ensued.

Lacy and Van then proceed to enumerate four major ways in which those “initial conditions” are different (read: scarier) today than they were in any of the previous 14 tightening cycles.

Got your life jacket ready? Lacy will be helping us hand them out at this year’s Strategic Investment Conference, May 22–25 in Orlando. And you’ve heard me say it before, but I’ll say it again: The President could do far worse than appointing Lacy Hunt to fill one of the two empty Fed governor seats.

Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook, Q1 2017

By Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington

Fed Tightening Cycles – Past and Present

The Federal Reserve has initiated the fifteenth tightening cycle since 1945 (Chart 1). Conspicuously, in 80% of the prior fourteen episodes, recessions followed, with outright business contractions being avoided in just three cases. What is notable today is that the economy is in the 93rd month of this expansion, a length of time that is well beyond periods in prior expansions where soft landings occurred (1968, 1984 and 1995). This is relevant because the pent-up demand from the prior downturn has been exhausted; thus, the economy is extremely vulnerable to a shock, which could lead to recession. Regardless of whether there was an associated recession, the last ten cycles of tightening all triggered financial crises. In conjunction with the non-monetary determinants of economic activity (referred to as initial conditions), monetary restraint served to expose over-leveraged parties and, in turn, financial crises ensued.

Four important considerations exist today that were not present in past cycles and that may magnify the current restraining actions of the Federal Reserve:

Poor Initial Conditions

To judge the success or failure of monetary or any other type of policy action, one must analyze in terms of the economic conditions under which the measures are being implemented. In other words, different starting points produce different results. Viewed from this perspective, the Fed’s current tightening is highly risk-prone for the economy.

Several factors that influence the economy (other than monetary policy) are far more problematic than those that existed in any of the prior tightening cycles. For instance, the U.S. is experiencing the weakest population growth since the 1930s and the lowest fertility rate since the records began. There has been a slowdown in the growth rate of household formation, and the U.S. has a rapidly aging society.

Economic growth. For the full calendar year 2016, nominal GDP rose just 3.0%, the weakest reported since 2009. Last year’s growth rate was even less than the cyclical lows associated with the recessions of 1990-91 and 2000-01. Rather unusually, at the March FOMC meeting, the Fed did not change its 2017 economic growth projections even though the broader first quarter indicators were even softer than last year, and their prior forecasts were made before they hiked the funds rate in December. Indeed, all of the key monetary variables that are heavily influenced by Fed policy operations deteriorated in the first quarter. Despite the lowest annual economic growth rate of this expansion and the second straight year of declining growth, no fiscal stimulus is expected for 2017. Monetary restraint implemented in late 2015 and 2016 has been followed by further restraint in 2017. How can the U.S. economy surge ahead this year with this additional restraint?

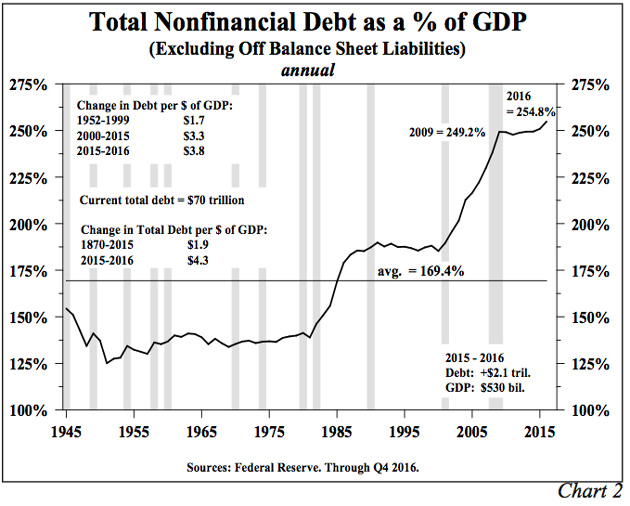

Debt. Total domestic nonfinancial debt, excluding off balance sheet liabilities such as leases and unfunded pension liabilities, surged to a record 254.8% of GDP in 2016, 5.6% greater than in 2009 when Lehman Brothers failed (Chart 2). Total debt, which includes domestic nonfinancial, foreign and bank debt, amounted to 372.5% of GDP in 2016, compared with 251.9% of GDP in 2006, the final year of previous tightening cycle, which, in turn, was greater than in any earlier time from 1870 through 2006.

The situation in the business sector deserves particular scrutiny. Business debt surged to a record 72.6% of GDP in 2016, for the first time eclipsing the prior peak of 70.2% reached in 2009. With the business sector so levered, not much room for miscalculation exists. As such, the risk is clearly present that the Fed’s restraint will chase out one or more heavily leveraged players, just as was the case in all the previous tightening cycles since the 1960s. Academic studies reflect that economic growth slows with over-indebtedness. Thus a powerful negative headwind is reinforcing the present monetary tightening.

The Fed Encounters Problems of Grand Design

Two macroeconomic textbooks (one written by Andrew B. Able (Wharton Professor) and Ben S. Bernanke (former Fed Chairman) and the other by N. Gregory Mankiw (Harvard Professor) both discuss over several chapters the transmission mechanism of monetary policy operations to the broader economy. Although they differ in some technical aspects, they both describe a very similar process as to how Fed restraint impacts economic conditions. Their independently taught process exactly describes what is unfolding in the reserve aggregates, short-term interest rates, bank loan volumes and the monetary aggregates today. However, the established process may more severely impact the economy because these actions are being taken in the aftermath of three unprecedented rounds of quantitative easing that have led to a massively enlarged Fed balance sheet (an action of “grand design”) coupled with the legislative adoption of the Dodd-Frank Law.

The late American sociologist, Robert K. Merton (1910-2003), who originated the concept of “unintended consequences”, identified the problems that arise when policy implements theories of grand design. Merton believed that middle range theories are superior to larger theories of grand design because larger theory outcomes are too distant for policy makers to realize how actions and reactions will change from the middle range theories under which they have typically operated. Merton argued that when dealing with broader, more abstract and untested theories, no effective way exists to test their success in advance.

We believe these are problems the Fed is already facing as their actions have changed the monetary landscape from previous periods of monetary restraint. The Fed (and the entire economy) is now caught in a new format that never existed, and thus is without the ability to anticipate the outcomes to policy because there is no historical reference point. We suspect that the results of the Fed’s tighter policies will be exacerbated by its own balance sheet and by the larger cash and liquidity requirements mandated by the Dodd-Frank Law. Not only must the textbooks be rewritten because of these legal and structural changes, but the Fed may also have to change the way it thinks about monetary policy’s transmission mechanism.

Contractions in the Monetary Base

To raise the policy rate, i.e., the federal funds rate, it is the theoretical norm for the Fed to act on the reserve aggregates, the most prominent of which is the monetary base and its subcomponents – total reserves and excess reserves. Able/Bernanke and Mankiw detail how changes in both influence economic conditions. The base, which is derived from a consolidated financial balance sheet of the Fed and Treasury, has an asset and liability side. On the latter, the base equals currency and total reserves. While the Fed does not have total command of the reserve aggregates in the short run, effective control is achieved over time.

The base is the key variable. If no fractional reserve-banking system existed, the liability side of the monetary base would be totally comprised of currency in circulation. In such an environment the central bank would have no power to change economic activity. On the other extreme, under a fractional reserve banking system where no one is allowed to hold any currency at all, the liability side of the monetary base would equal total reserves of the banking system. Changes in the Fed’s portfolio of assets would result in dollar for dollar changes in bank reserves. This still might not greatly change the central bank’s economic power. Whether depository institutions would put all of the total reserves to use in creating money and credit would still depend on a whole host of other considerations, including interest rates, the capital of the banks, the balance sheet of the potential nonbank borrowers and numerous other factors.

Historically, the higher funds rate was reached by a slower but still positive growth rate in the monetary base. This caused the upward- sloping credit supply curve to shift inward, thus hitting the downward sloping credit demand curve at a higher interest rate level. In graphic terms, the price of credit, which is the vertical component of a supply and demand diagram, is the policy rate, and the horizontal component is the volume demand for credit. The shift in the supply curve reduces the depository institutions capability to make loans while the higher interest rate also serves to reduce the demand for credit. The textbook writers do not add to the complexity of interest rate changes when, like now, the economy is heavily indebted. A small increase in interest rates leads to a large and quick increase in interest expense. But, current conditions differ from the textbook cases due to two powerful considerations.

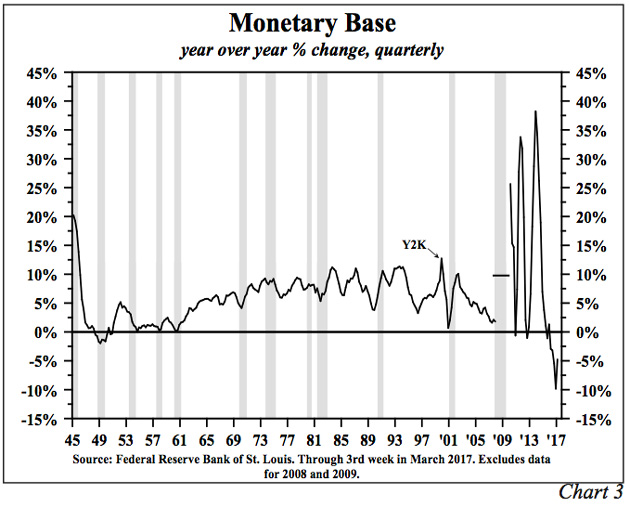

First, in the initial quarter of 2017, the year-over-year change in the monetary base was -4.8%. This comes after sharp contractions in each of the previous four quarters, the largest such decreases since the end of World War II (Chart 3). Some argue that this unprecedented weakness in the monetary base is not relevant since the depository institutions still hold $2.1 trillion of excess reserves (defined as the difference between total reserves and required reserves). The textbook writers emphasize that excess reserves are the key to money and credit expansion. But, the multiple expansion of bank reserves so diligently explained in the textbooks was written for a regulatory environment that no longer exists, which is the second different condition.

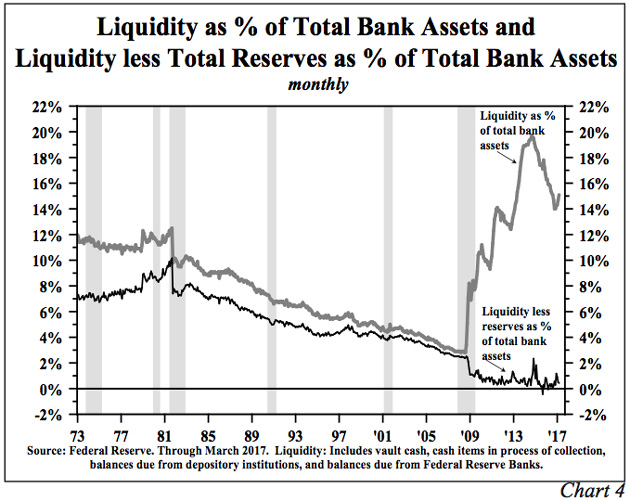

Beginning in 2015, large banks as well as banks with substantial foreign exposure are required to have a 100% or greater “liquidity coverage ratio” (LCR). This means the banks must hold an amount of highly liquid assets (such as reserve balances at the Federal Reserve Banks and Treasury securities) equal to or greater than the difference between their cash outflows and inflows over a 30-day stress period. Thus, excess reserves are irrelevant to the money creation process if the reserve balances are needed to achieve a 100% LCR. In line with the decline in excess reserves, there has been a dramatic reduction in bank liquidity, which has fallen nearly 17% (Chart 4). This reduction brings bank liquidity much closer to its LCR, altering bank management practices. Based upon an examination of all the monetary indicators closely linked to the policy rate and the reserve aggregates, the probability exists that the Fed, with three small increases in the fed eral funds rate, has now turned the money / credit creation process negative.

The Monetary and Credit Aggregates Respond

Since the Fed raised the federal funds rate in December 2015, the growth rates of the monetary and credit aggregates have slowed. In addition, banks have pursued tightening credit standards. As such, these developments are indicative of the changed ground rules.

In the past six months, the M2 money stock grew at a 5.9% annual rate, down from a 2016 increase of 6.8%, which is near the average increase in M2 since 1900. Thus, in a very short span, M2 has fallen from a trend rate of growth onto a slower path. The additional rate increase in March suggests that M2’s growth rate will moderate further over the remainder of the year. U.S. Treasury balances at the Federal Reserve Banks fell sharply in the first quarter due to extraordinary measures used to avoid hitting the debt ceiling. Dropping Treasury balances, all other things being equal, would boost M2. Thus a normalization of Treasury balances, assuming a debt ceiling resolution, will tend to slow M2 growth further.

Growth in the credit aggregates has slumped even more dramatically than M2, thus confirming and reinforcing the significance of the weakness in money. Growth in total commercial bank loans and leases slowed from an 8.0% rise in the first quarter of 2016 to 5.0% in the fourth quarter of last year. Although the figures for the first quarter are not yet complete and subject to revision, bank loans were essentially unchanged. Commercial and industrial loans, however, actually fell in the first quarter, a substantial turnaround from the 10.8% rate of increase in the first quarter of 2016. Residential real estate loans also fell in the first quarter, compared with a 4.0% rate of rise in the first quarter of 2016. Consumer loan growth remained positive in the first quarter, but the rate of increase was sharply cut.

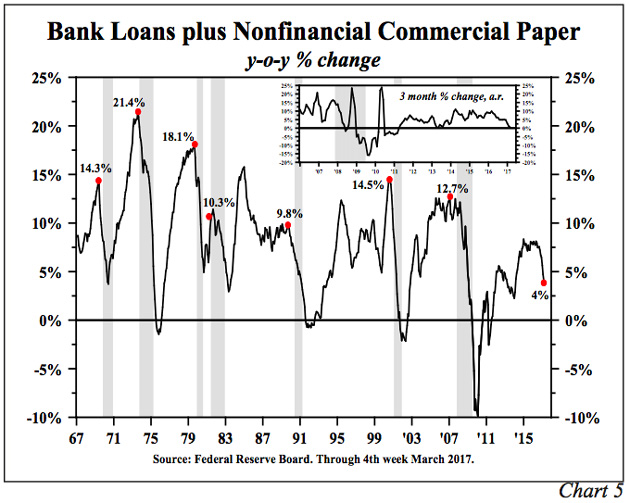

The most notable credit aggregate – total bank loans and leases plus nonfinancial commercial paper – has turned increasingly weak. In March this broad credit measure was just 4% higher than a year earlier and one half the peak growth rate registered in this current economic expansion that began in 2009 (Chart 5). As seen in Chart 5, the year-over-year changes in this aggregate indicate this is a very cyclically sensitive economic indicator. The year-over-year growth peaked prior to, or in the early stages of, all the recessions since 1969. Moreover, the latest growth rate is slower than at the entry point of the past seven recessions. In the last three months, no growth was registered in total loans and nonfinancial commercial paper. Historically, the three-month growth has not been this weak until the economy is already in recession.

Traditionally, money and credit slowdowns have resulted in tighter bank lending standards, and this is currently the case. In the first quarter survey of senior bank lending officers, almost 10% of the banks were tightening standards for both credit card and other consumer type loans. This was almost identical to the percentage when the economy entered the 2000 and 2008 recessions. Standards for commercial real estate loans have also been raised and in the first quarter were just below the levels when the economy entered the last two recessions.

In summary, monetary restraint is taking hold in all the different ways of measuring the Fed’s actions in a late stage expansion where historically the final result was either a recession, a financial crisis or both.

Repeated Results

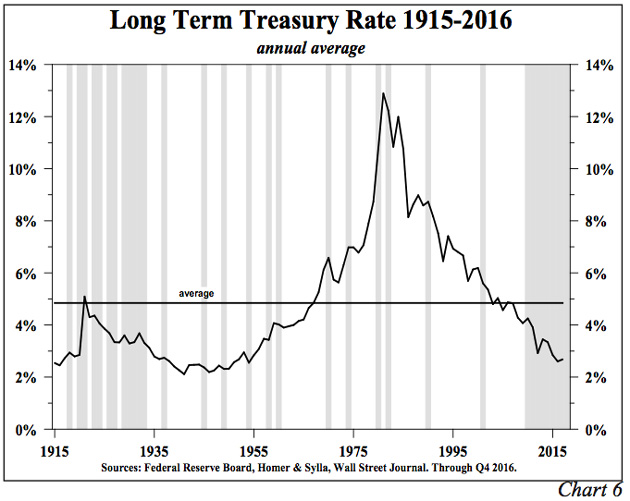

A century of Federal Reserve tightening cycles has left an indelible mark on the U.S. business cycle. Looking at the period from 1915 through the present, the Fed has typically tightened too much and/or for too long. From this long history, a well-established pattern is identifiable. The economic growth rate along with inflation receded. A financial crisis was more likely than not. With different lags, which were influenced by the initial conditions, bond yields dropped along with falling inflationary expectations (Chart 6). The cyclical trough in Treasury bond yields typically occurred several years after the end of the economic contraction. This long empirical record, as well as economic theory, indicates that the current Fed tightening cycle will not end any differently.

Looking Ahead

Our economic view for 2017 remains unchanged. We continue to anticipate no more than 2% growth in nominal GDP for the full calendar year. This is in line with the recent trends in M2 growth coupled with an anticipated decline in M2 velocity of 3.6% (M2*V=GDP). The risks, however, are to the downside. M2 was probably boosted by what will eventually be a transitory drop in Treasury balances at the Fed. Although not the main determinant, a rise in short-term rates would negatively influence velocity. The downturn in nominal GDP growth suggests that a rise in inflation to above 2% will be rejected and that by year end the inflation rate will be considerably slower. In such an economic environment long-term Treasury yields should continue to work irregularly lower over the balance of the year.

Our view on bond yields does not change if the Fed further boosts the federal funds rate this year. Any additional increases will place further downward pressure on the reserve, monetary and credit aggregates as well as tighten bank lending standards. Such actions will not allow the economy to regain the economic momentum that was lost in 2016 and in the early part of this year. Thus, the secular low in bond yields remains in the future, not the past.

Van R. Hoisington

Lacy H. Hunt, Ph.D. |

Quote of the day

“I find economics increasingly satisfactory, and I think I am rather good at it.”– John Maynard Keynes

Friday, 28 April 2017

Fed tightening cycle as per the lesson

Quick intro, and it is a lot to read - try and identify one or two points that you can use in an essay; for most the sheet we discussed in class will be enough. This is highly technical, but should be accessible for some of you:

Labels:

banks,

central bank,

federal reserve,

mauldin,

monetary policy,

trade cycle

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment