It is Time to Change How We View Foreign Direct Investment

FDI is increasingly driven by tax avoidance.

December 17, 2019

A lot of financial globalization has been driven by tax avoidance.

40 percent of FDI globally comes from just seven countries, which collectively account for 3 percent of the world economy.

More on:

That’s one striking result of a new IMF working paper.

It paints a picture of foreign direct investment that runs a bit against the common view of foreign direct investment as the virtuous, and low risk, form of financial integration.

Foreign direct investment is generally thought to be real investment in plant and equipment abroad—GE building gas turbines in France, GM building cars in China, Siemens building turbines in North Carolina, and BMW and Toyota building cars in South Carolina and Kentucky.

Statistically, though, FDI is often investment by one special purpose entity (generally located in a tax center) in another special purpose entity…so called phantom FDI.

That is why it is time to start viewing the direct investment data with a more jaundiced eye.

One of the biggest recent “direct” investments globally was Microsoft Ireland’s purchase of Microsoft Singapore. That transaction has a huge statistical impact on Ireland (and the euro area), but didn’t have much of an impact on the “real” Irish economy.

That same critical eye also needs to applied to the data on direct investment into and out of the United States, as it too is heavily influenced by transactions that are likely motivated primarily by tax considerations.

Consider the data on outward U.S. direct investment abroad.

That data historically has been dominated by “reinvested” earnings—the profits American firms earn abroad that they legally kept in their offshore subsidiaries.

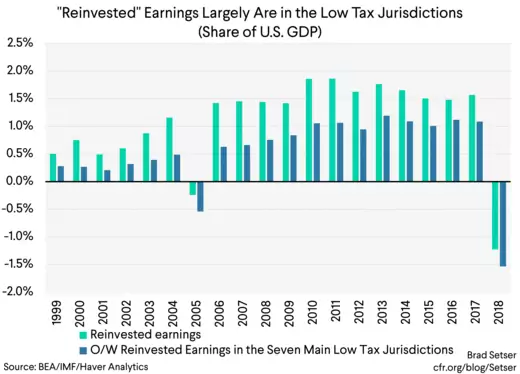

This was the source of the supposedly offshore cash stash of U.S. firms (the funds were only legally offshore, as they legally were assets of say Apple Ireland or Microsoft Bermuda; in practice they were invested in U.S. financial assets—and firms that wanted to access their offshore cash to say buyback their shares could do so by borrowing against their offshore cash). The bulk of those reinvested earnings—if you looked closely in the data—weren’t being reinvested in physical assets, but rather were piling up in the offshore subsidiaries U.S. firms had established in low tax jurisdictions. From 2010 to 2018, 65 percent of all reinvested earnings were “reinvested” in jurisdictions like Ireland and Bermuda (which works out to about $200b a year of investment in those jurisdictions, or about half of all US FDI in the “pre-tax reform” data).

That clearly was a function of firms’ ability to defer paying U.S. tax on otherwise un-taxed global profits under the old tax law. Profits earned in high tax jurisdictions didn’t have any U.S. tax liability under the old law, as firms could deduct taxes actually paid abroad. Indefinite deferral effectively distorted the global data—raising the amount of U.S. direct investment abroad (the cash Apple held in Ireland was an asset of Apple USA, so reinvestment raised the stock of U.S. equity assets abroad even if technically the equity investment abroad was the accumulation of offshore cash) and the amount of foreign claims on the United States (U.S. treasuries purchases by Apple Ireland were counted as foreign holdings of U.S. government debt, that’s why Ireland was at one time the world’s third largest holder of U.S. Treasuries).

No comments:

Post a Comment