How negative can interest rates go?

As global bond yields plumb new depths, an unprecedented experiment in monetary policy is underway in two small countries in Europe. By pushing policy interest rates more deeply into negative territory than ever seen before, the Swiss and Danish central banks are testing where the effective lower bound on interest rates really lies. The results are being closely watched by bond investors, and by the major central banks, which had previously assumed that the effective lower bound was close to zero.

The Danish central bank cut interest rates to -0.5 per cent last week, the third cut in the last two weeks. The Swiss National Bank cut its deposit rate to -0.75 per cent when it recently removed the ceiling on the Swiss franc.

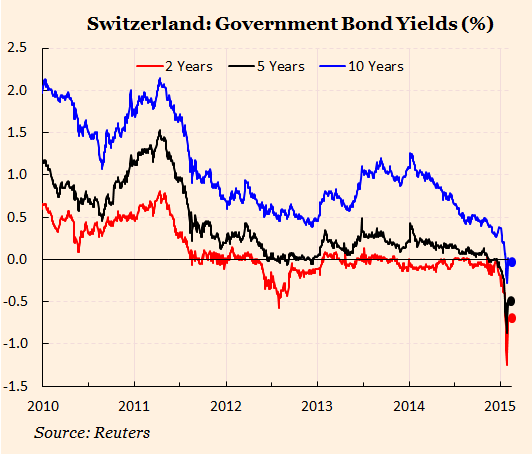

Money market rates in Switzerland have fallen to a low of -0.96 per cent. Bond yields have followed suit, right across the curve (see graph). Those who believed that long bond yields could not go negative have had a rude awakening.

Denmark and Switzerland are clearly both special cases, because they have been subject to enormous upward pressure on their exchange rates. However, if they prove that central banks can force short term interest rates deep into negative territory, this would challenge the almost universal belief among economists that interest rates are subject to a zero lower bound (ZLB).

During the financial crash, central bankers held policy rates just above zero. The Federal Reserve stopped cutting at 0-0.25 per cent and the Bank of England at 0.5 percent. They both quoted practical or institutional reasons for believing that rates could fall no further. There were fears that the money market computer systems would be technically unable to function with negative rates, and worries about squeezing profits in the financial sector [1].

Some of these practical and institutional concerns have now faded. The money markets have continued to function smoothly in the countries that have gone negative, including the Eurozone. In Congressional testimony last year, Fed Chair Yellen suggested that negative rates were something that the Fed “could consider going forward”, but she thought that the benefits would be fairly small. In any event, the US and UK focus has now shifted to the question of when to raise policy rates, so the binding nature of the ZLB is less pressing.

The lower bound is, however, a live policy concern for the ECB and the Bank of Japan, both of which might one day choose to cut nominal rates further if they believed it could be done as a practical matter. So far, they have shown little appetite for this. The ECB has stated firmly that the lower bound on its deposit rate is -0.2 per cent, and the Bank of Japan is focused on asset purchases, not rate cuts.

However, the global bond markets are bound to be affected not just by the near term outlook for short rates, but by the assumed lower limit on rates in the long term. Bonds are presently priced on the assumption that forward short rates cannot drop far below zero for very long. When interest rates are low, this causes an asymmetry in the yield curve, because the possible range for future short rates is truncated at zero. Swiss experience suggests that yields fall throughout the curve, and the curve steepens, when the ZLB constraint is relaxed.

The second graph shows roughly what could happen to the German yield curve if the market decided that the ECB could cut short rates to -0.8 per cent, and hold them there for 4 years, compared to the current curve, which is based on a lower bound of -0.20 per cent for short rates. The difference is quite marked, in line with recent Swiss experience.

However, there is of course a large stumbling block to all of this speculation, and that is the existence of cash in the economy. Banknotes are essentially a zero yielding form of government paper that also provides the benefit of providing legal tender (subject to certain limits). If the central banks were to drive the yields on bank deposits too far into the negative zone, banks and eventually their customers would choose to hold cash instead of the negative yielding deposits [2]. Ultimately, if pushed too far, the entire economy would become a cash based system. That is the real constraint on the ability of the central banks to set negative interest rates.

But cash is very inconvenient to hold and use for large transactions. It can be stolen or lost, so most honest citizens would be willing to hold bank deposits even if they are charged a negative yield for doing so. The key question is how valuable these benefits of security and convenience really are: the more valuable they are judged to be, the further negative that the central banks can drive interest rates on deposits without causing an implosion in the banking system.

In the past, economists have always assumed that the convenience yield on bank deposits is extremely small, so there would be a stampede into cash, led by the banks themselves, if the yield on deposits at the central bank went even slightly negative. But no one really knows whether that is true. In the long term, new businesses would appear, helping the private sector to handle and store cash cheaply and efficiently, but this may not happen quickly. And the central bank could make this more difficult by placing limits on access to large denomination banknotes [3].

There is, though, another constraint on negative interest rates. That is social and political. Negative rates on bank deposits at the central bank are frequently described as a tax on the banks, and that becomes a tax on savers when it is passed on to citizens’ bank deposits. It seems quite likely that savers will be much more incensed by negative rates than they have been by a similar sized move in rates while they are in positive territory (or indeed by an erosion in the real value of their savings via inflation). This would not necessarily be fully rational, but it could be a powerful political force.

All this is now being seriously tested, for the first time anywhere in the world, by the Swiss and the Danes. Early indications suggest that the effective lower bound on rates, at least for short periods, may be lower than economists have previously supposed.

———————————————————————————————————-

Footnotes

[1] In the US, there were fears that money market funds, which had given implicit guarantees to their investors that they would not “break the buck” by reducing net asset values below zero, would go bust if the Fed offered negative rates on deposits. In the UK, the Bank of England was concerned that negative base rates would put the building societies under pressure, because their “tracker” mortgage rates would fall more than their deposit rates.

[2] There could also be switches into foreign currency deposits, gold and other assets, but each of these involves new relative risks for the deposit holder (eg exchange rate risks, or asset price risks) and decisions should be affected by relative rates of returns on banks deposits versus these other assets, whether absolute interest rates are positive or negative. Cash is the ultimate constraint on negative absolute interest rates on bank deposits, because it does not involve taking new risks, and because its yield is always zero.

[3] The ZLB could be eliminated altogether by introducing taxes on cash holdings, or electronic money, but these radical options are not considered here.

The Danish central bank cut interest rates to -0.5 per cent last week, the third cut in the last two weeks. The Swiss National Bank cut its deposit rate to -0.75 per cent when it recently removed the ceiling on the Swiss franc.

Money market rates in Switzerland have fallen to a low of -0.96 per cent. Bond yields have followed suit, right across the curve (see graph). Those who believed that long bond yields could not go negative have had a rude awakening.

Denmark and Switzerland are clearly both special cases, because they have been subject to enormous upward pressure on their exchange rates. However, if they prove that central banks can force short term interest rates deep into negative territory, this would challenge the almost universal belief among economists that interest rates are subject to a zero lower bound (ZLB).

During the financial crash, central bankers held policy rates just above zero. The Federal Reserve stopped cutting at 0-0.25 per cent and the Bank of England at 0.5 percent. They both quoted practical or institutional reasons for believing that rates could fall no further. There were fears that the money market computer systems would be technically unable to function with negative rates, and worries about squeezing profits in the financial sector [1].

Some of these practical and institutional concerns have now faded. The money markets have continued to function smoothly in the countries that have gone negative, including the Eurozone. In Congressional testimony last year, Fed Chair Yellen suggested that negative rates were something that the Fed “could consider going forward”, but she thought that the benefits would be fairly small. In any event, the US and UK focus has now shifted to the question of when to raise policy rates, so the binding nature of the ZLB is less pressing.

The lower bound is, however, a live policy concern for the ECB and the Bank of Japan, both of which might one day choose to cut nominal rates further if they believed it could be done as a practical matter. So far, they have shown little appetite for this. The ECB has stated firmly that the lower bound on its deposit rate is -0.2 per cent, and the Bank of Japan is focused on asset purchases, not rate cuts.

However, the global bond markets are bound to be affected not just by the near term outlook for short rates, but by the assumed lower limit on rates in the long term. Bonds are presently priced on the assumption that forward short rates cannot drop far below zero for very long. When interest rates are low, this causes an asymmetry in the yield curve, because the possible range for future short rates is truncated at zero. Swiss experience suggests that yields fall throughout the curve, and the curve steepens, when the ZLB constraint is relaxed.

The second graph shows roughly what could happen to the German yield curve if the market decided that the ECB could cut short rates to -0.8 per cent, and hold them there for 4 years, compared to the current curve, which is based on a lower bound of -0.20 per cent for short rates. The difference is quite marked, in line with recent Swiss experience.

However, there is of course a large stumbling block to all of this speculation, and that is the existence of cash in the economy. Banknotes are essentially a zero yielding form of government paper that also provides the benefit of providing legal tender (subject to certain limits). If the central banks were to drive the yields on bank deposits too far into the negative zone, banks and eventually their customers would choose to hold cash instead of the negative yielding deposits [2]. Ultimately, if pushed too far, the entire economy would become a cash based system. That is the real constraint on the ability of the central banks to set negative interest rates.

But cash is very inconvenient to hold and use for large transactions. It can be stolen or lost, so most honest citizens would be willing to hold bank deposits even if they are charged a negative yield for doing so. The key question is how valuable these benefits of security and convenience really are: the more valuable they are judged to be, the further negative that the central banks can drive interest rates on deposits without causing an implosion in the banking system.

In the past, economists have always assumed that the convenience yield on bank deposits is extremely small, so there would be a stampede into cash, led by the banks themselves, if the yield on deposits at the central bank went even slightly negative. But no one really knows whether that is true. In the long term, new businesses would appear, helping the private sector to handle and store cash cheaply and efficiently, but this may not happen quickly. And the central bank could make this more difficult by placing limits on access to large denomination banknotes [3].

There is, though, another constraint on negative interest rates. That is social and political. Negative rates on bank deposits at the central bank are frequently described as a tax on the banks, and that becomes a tax on savers when it is passed on to citizens’ bank deposits. It seems quite likely that savers will be much more incensed by negative rates than they have been by a similar sized move in rates while they are in positive territory (or indeed by an erosion in the real value of their savings via inflation). This would not necessarily be fully rational, but it could be a powerful political force.

All this is now being seriously tested, for the first time anywhere in the world, by the Swiss and the Danes. Early indications suggest that the effective lower bound on rates, at least for short periods, may be lower than economists have previously supposed.

———————————————————————————————————-

Footnotes

[1] In the US, there were fears that money market funds, which had given implicit guarantees to their investors that they would not “break the buck” by reducing net asset values below zero, would go bust if the Fed offered negative rates on deposits. In the UK, the Bank of England was concerned that negative base rates would put the building societies under pressure, because their “tracker” mortgage rates would fall more than their deposit rates.

[2] There could also be switches into foreign currency deposits, gold and other assets, but each of these involves new relative risks for the deposit holder (eg exchange rate risks, or asset price risks) and decisions should be affected by relative rates of returns on banks deposits versus these other assets, whether absolute interest rates are positive or negative. Cash is the ultimate constraint on negative absolute interest rates on bank deposits, because it does not involve taking new risks, and because its yield is always zero.

[3] The ZLB could be eliminated altogether by introducing taxes on cash holdings, or electronic money, but these radical options are not considered here.

No comments:

Post a Comment