This graphic tells a grim story:

It would appear the answer is a resounding "yes"! This leads to 2 questions:

1. What happens when the bubble bursts?

2. Can the US central bank do anything to help when it does?

Quote of the day

“I find economics increasingly satisfactory, and I think I am rather good at it.”– John Maynard Keynes

Tuesday, 27 December 2016

Is the US in the throes of another housing bubble?

Consider these ten fundamental laws of economics

MISES WIRE

A

A

Ten Fundamental Laws of Economics

12/20/2016 Antony P. Mueller

In the midst of so many economic fallacies being repeatedly seemingly without end, it may be helpful to return to some of the most basic laws of economics. Here are ten of them that bear repeating again and again.

1. Production precedes consumption

Although it is obvious that in order to consume something it must first exist, the idea to stimulate consumption in order to expand production is all around us. However, consumption goods do not just fall from the sky. They are at the end of a long chain of intertwined production processes called the “structure of production.” Even the production of an apparently simple item such as a pencil, for example, requires an intricate network of production processes that extend far back into time and run across countries and continents.

2. Consumption is the final goal of production

Consumption is the objective of economic activity, and production is its means. The advocates of full employment violate this obvious idea. Employment programs turn production itself into the objective. The valuation of consumption goods by the consumers determines the value of production goods. Current consumption results from the production process that extends to the past, yet the value of this production structure depends on the current state of valuation by the consumers and the expected future state. Therefore, the consumers are the final de facto owners of the production apparatus in a capitalist economy.

3. Production has costs

There is no such thing as a free lunch. Getting something apparently gratis only means that some other person pays for it. Behind every welfare check and each research grant lies the tax money of real people. While the taxpayers see that government confiscates part of one’s personal income, they do not know to whom this money goes; and while the recipients of government expenditures see the government handing the money to them, they do not know from whom the government has taken away this money.

4. Value is subjective

Valuation is subjective and varies with the an individual’s situation. The same physical good has different values to different persons. Utility is subjective, individual, situational and marginal. There is no such thing as collective consumption. Even the temperature in the same room feels differently to different persons. The same football match has a different subjective value for each viewer as can be easily seen the moment when a team scores.

5. Productivity determines the wage rate

The output per hour determines the worker’s wage rate per hour. In a free labor market, businesses will hire additional workers as long as their marginal productivity is higher than the wage rate. Competition among the firms will drive up the wage rate to the point where it matches productivity. The power of labor unions may change the distribution of wages among the different labor groups, but trade unions cannot change the overall wage level, which depends on labor productivity.

6. Expenditure is income and costs

Expenditure is not only income, but also represents costs. Spending counts as costs for the buyer and income for the seller. Income equals costs. The mechanism of the fiscal multiplier implies that costs rise with income. In as much as income multiplies, costs multiply as well. The Keynesian fiscal multiplier model ignores the cost effect. Grave policy errors are the result when government policies count on the income effect of public expenditures but ignore the cost effect.

7. Money is not wealth

The value of money consists in its purchasing power. Money serves as an instrument of exchange. The wealth of a person exists in its access to the goods and services he desires. The nation as a whole cannot increase its wealth by increasing its stock of money. The principle that only purchasing power means wealth says that Robinson Crusoe would not be a penny richer if he found a gold mine on his island or a case full of bank notes.

8. Labor does not create value

Labor, in combination with the other factors of production, creates products, but the value of the product depends on its utility. Utility depends on subjective individual valuation. Employment for sake of employment makes no economic sense. What counts is value creation. In order to be useful, a product must create benefits for the consumer. The value of a good exists independent from the effort of producing it. Professional marathon runners do not earn more prize money than sprinters because running the marathon takes more time and effort than a sprint.

9. Profit is the entrepreneurial bonus

In competitive capitalism, economic profit is the extra bonus that those businesses earn that fix allocative errors. In an evenly rotating economy with no change, there would be neither profit nor loss and all companies would earn the same rate of interest. In a growing economy, however, change takes place and anticipating changes is the source of economic profits. Business that does well in forecasting future demand earn high rates of profit and will grow, while those entrepreneurs who fail to anticipate the wants of the consumers will shrink and finally must shut down.

10. All genuine laws of economics are logical laws

Economic laws are synthetic a priori reasoning. One cannot falsify such laws empirically because they are true in themselves. As such, the fundamental economic laws do not require empirical verification. Reference to empirical facts serve merely as illustrative examples, they are not statements of principles. One can ignore and violate the fundamental laws of economics but one cannot change them. Those societies fare best where people and government recognize and respect these fundamental economic laws and use them to their advantage.

German-born Antony Mueller teaches economics at the Federal University of Sergipe (UFS) in Brazil. See his website, blog, youtube channel, tumblr.

Thursday, 15 December 2016

2 articles exposing Italy's problems - worse than Brexit?

Italy poses a huge threat to the euro and union

By Wolfgang Münchau

Originally published in the Financial Times, December 11, 2016

Originally published in the Financial Times, December 11, 2016

One day the country will be led by a party in favour of withdrawal from the currency.

Chronic inability to separate the probable from the desirable has been the tragedy of 2016. Wishful thinking is becoming a threat to the survival of liberalism itself.

This tendency is especially evident in the discussion about Italy’s future in the eurozone. The complacent now say that Italy is good at muddling through; that the establishment can always stitch up the electoral system to prevent a victory by an extremist party. In any case, the Italian constitution does not allow for a referendum on leaving the euro. So it cannot happen.

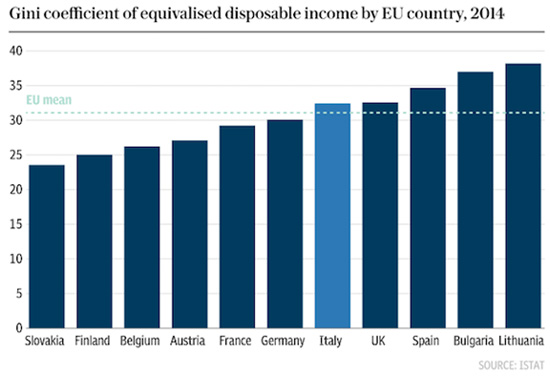

Really? I don’t think so. Start with the discrepancy in economic performance between Germany and Italy. One metric is the imbalances within Target 2, the eurozone’s payment system. At the end of November these reached higher levels than during the height of the eurozone crisis in 2012. Germany’s surplus is at €754bn, while Italy’s deficit is at €359bn. A part of the imbalances relates to the European Central Bank’s programme of quantitative easing, and is thus harmless. But the bulk is due to what might be described as a silent bank run.

Lack of sustainability does not necessarily imply exit. It is possible, in theory, that the political will overrides the economic needs for ever. Or that the unsustainable could be rendered sustainable. For that to happen, at least one of five conditions would have to be fulfilled.

First, Italy and Germany could converge. To do this, Italy would need to undertake economic reforms to clean up the justice system and the public administration, cut taxes and invest in productivity-increasing technologies. Germany would need to run a higher fiscal deficit. Second, the northern European states accept large fiscal transfers to the south. Third, the EU creates a federal political authority with powers to raise taxes in order to transfer income from high to low-income earners. Fourth, the ECB finds a way to bankroll Italian public and private debt indefinitely. Or fifth, Italy’s government will forever continue to support euro membership.

Only one of those five conditions may be sufficient for Italy to remain a member of the euro. The problem is that each one is extremely improbable. And I cannot think of a sixth one.

Matteo Renzi’s economic reforms have been insignificant, apart from a smallish labour reform package. The former Italian prime minister chose to focus on political reforms instead, and lost when the referendum returned a 60 per cent No vote. After his failure, a reformist government is not in sight.

The selection of Paolo Gentiloni to replace Mr Renzi is not going to change that. His government, after all, has a very narrow mandate. I also cannot see Germany bailing out the eurozone — either before or after next year’s national elections. The country’s constitution requires a balanced budget. No other northern state is willing to accept large fiscal transfers, let alone a political union.

What about the ECB? Last week, it extended its QE initiative until the end of 2017. The programme has helped Italy but it will not be sufficient to bankroll the country indefinitely, especially given the small size of the programme relative to the total outstanding public debt.

This leaves us with Italian politics. Of the three large party groups, only the centre-left Democratic party (PD), Mr Renzi’s party, is pro-euro. There is a theoretical possibility that a resurgent PD might win the next election. I am not sure this will happen but I am sure that the PD cannot remain in power indefinitely.

One day Italy will be led by a party in favour of withdrawal from the euro. When that happens, euro exit would turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy. There would a run on Italy’s banks and its government’s bonds.

Italy’s fate in the eurozone and the possibility of a President Marine Le Pen of France are two large threats to the eurozone and the EU. If Italy wants to stay in the euro, it needs to send a clear warning to Germany and the other northern European countries that the eurozone is set on a path of self-destruction unless there is a change of parameters.

The next Italian prime minister will need to explain to the next German chancellor, presumably Angela Merkel, that her choice will not be between a political union or no political union, but between a political union or Italy’s withdrawal from the euro.

The latter would imply the biggest default in history. The German banking system would be in danger of collapsing, and Europe’s biggest economy would lose all the competitiveness gains so painstakingly accumulated over the past 15 years.

It has been the historic failure of consecutive Italian prime ministers to avoid this necessary confrontation, and to think that staying off the radar screen constitutes a viable strategy.

Italy’s rebel economist hones plan to ditch the euro and restore the Medici florin

By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

Originally published in the Telegraph, December 6, 2016

Originally published in the Telegraph, December 6, 2016

The once-unlikely and remote prospect of an anti-euro government in Italy is suddenly becoming a real possibility, threatening to rock the European Union to its foundations within weeks.

Events in Italy are moving with lightning speed. Key figures in the Democrat Party of premier Matteo Renzi have joined the chorus of calls for snap elections as soon as February to prevent the triumphant Five Star Movement running away with the political initiative after their victory in the referendum over the weekend.

Mr Renzi has not yet revealed his hand but close advisers say he is tempted to gamble everything on a quick vote, betting that he still has enough support to squeak ahead in a contest split multiple ways and that his opponents are not ready for the trials of an election.

It could easily spin out of his control, opening a way for a tactical alliance of Five Star, the Lega Nord, and a smattering of small groups, all critics of the euro in various ways.

The man tipped as possible finance minister of any rebel constellation is Claudio Borghi, a former broker for Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank, and now a professor at the Catholic University of Milan.

“We are coming to the point where Italy must the make the real decision: are we for Europe or are we against it?” he told the Telegraph.

“What is emerging is a list of four parties or groups who all have one thing in common. We all agree that nothing is possible until we leave the euro.”

“Europe has brought us a depression worse than 1929. It has led to entire peoples being broken and humiliated, like the Greeks, all for the sake of preserving the infernal instrument of the euro. This whole disaster has been adorned by a chain of lies, shouted ever louder because they are afraid that the colossal damage they have done will be discovered,” he said.

Dr Borghi said the landslide 59:41 result in the referendum is a shock to Italy’s powerful vested interests, or “poteri forti”. “They are absolutely scared because none of their tools of control are working any more,” he said.

“They invested huge prestige in the campaign. Confindustria [Italy’s CBI], the chambers of commerce, and all of Italy’s big employers were for the ‘Yes’ side. They said the banks would collapse, that we would lose all our savings, and that we would all go to Hell if we voted ‘No’, but it didn’t work. It was Brexit reloaded,” he said.

Professor Borghi said withdrawal from the euro would be messy but there are ways of mitigating the effects, first by creating parallel liquidity and letting it seep into daily life.

“The Italian treasury has €90 billion (£76 billion) in arrears on contracts. These could be paid with treasury bonds issued for as little as €50, €20, €10, or even €5, giving us time to create a second currency.

“When the time comes we can then switch to this new currency. It can be done electronically. We don’t even need to print paper,” he said.

Prof Borghi said the cleanest option is for Germany to leave the eurozone. If that is impossible Italy can pass a law to convert its debt obligations into lira overnight – or the ‘florin’ as he prefers to call it, harking back to the days of Florentine ascendancy under the Medici.

“The losses would shift to the national central banks through the Target2 system,” he said. This means the Bank of Italy would repay €355bn on liabilities to eurozone peers (chiefly the Bundesbank) in devalued lira. The Bundesbank would face instant paper losses on its credits – effecting €700bn in the likely event that an Italian exit would lead to a general return to sovereign currencies.

The sums are in one sense an accounting fiction. The trial run was the collapse of the Swiss franc peg against the euro in January 2015. The Swiss National Bank suffered vast theoretical loses on its holdings of eurozone debt when the franc revalued, but life went on regardless.

The gamble is that large sums held by Italians in accounts in London, New York, Paris, or Munich, or held in safe-deposit boxes in Switzerland, would flow back into the system as soon as the boil is lanced, and once Italy has returned to exchange rate viability. Foreign investors would view Italy as a far more competitive prospect.

“I don’t see any disaster. There is no way to smash our currency since we have a trade surplus. If we had a weaker exchange rate we would have an even bigger surplus,” he said.

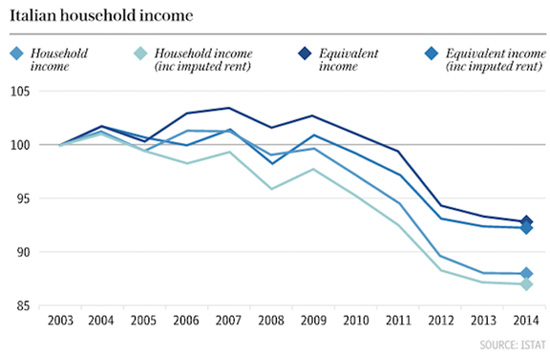

For Italy’s eurosceptics a return to the lira would be a liberation after fifteen years of economic decay that has hollowed out the country’s manufacturing core. Industrial output has fallen back to the levels of 1980. Real GDP per capita is down 13pc from its peak.

A report this week from the statistics agency ISTAT said the numbers at risk from poverty and social exclusion last year rose to 28.7pc, and a fresh high of 46.4pc in South, and 55pc in Sicily – the epicentre of the ‘No’ vote in the referendum.

A study by Mediobanca found that Italy’s growth rate tracked that Germany almost exactly for thirty years. The pattern changed with the advent of the euro, which precluded devaluations and led to a slow but fatal loss of labour competitiveness – like a lobster being boiled alive.

This was compounded by the eurozone’s fiscal and monetary contraction from 2010-2104, a policy error that caused the EMU debt crisis and led to a double-dip recession. This is turn pushed Italy over the edge and into a banking crisis.

Exit from the euro would give the country the fiscal freedom to break out of its deflationary trap, and to save its banking system with a state-led recapitalization along the lines of the TARP programme in the US – forbidden under EU state aid laws, unless Italy agrees to swallow the draconian terms of an EU bail-out.

Prof Borghi said the EU’s new ‘bail-in’ rules must be swept aside. “As soon you start wiping out savers and bondholders – who did not behave recklessly – you are telling people that their money is not safe in the bank,” he said.

“All the EU has achieved is a collapse in Italian banking stocks by 85pc since last November. You have to step in to save the banking system in a crisis otherwise everything is destroyed,” he said.

Prof Borghi is chief economic strategist for the Right-wing Lega Nord, but what is emerging is a tactical alliance between his party and the Five Star Movement, which has more in common with the Left. The two together are running at 44pc in the polls. Their economists are working together in what is becoming a closely-knit school of eurosceptics.

The grass roots of the Five Star party have always been hostile to pacts with any other group, regarding the whole political cast in Italy as rotten to the core. But Mr Grillo says the party is closing in on power and must be prepared to make compromises. “We are in a spiral towards government,” he said.

Prof Borghi is under no illusion that leaving the euro can alone solve Italy’s deep-rooted problems, but ’Italexit’ is a minimum condition. “It is going to be hard, but without our own correctly-valued currency, we are not going to be able to do anything however hard we try,” he said.

Saturday, 3 December 2016

Italy referendum on Sunday - does this chart have any effect on outcome?

There is a very strong chance of an Italian banking crisis within a few quarters; this would put Italy in a similar position to Greece - except the Italians have seen what the Troika did to Greece, and so won't be looking for that sort of "help".

Labels:

euro,

Europe,

European Union,

GDP,

Italy,

unemployment

Friday, 2 December 2016

Is HS2 already obsolete?

Perhaps, if this works planned:

The Hyperloop was the stuff of science fiction a few years ago, but now it is close to a reality. What will this do to vast investments like HS2?

The Hyperloop was the stuff of science fiction a few years ago, but now it is close to a reality. What will this do to vast investments like HS2?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)