Swiss banking group UBS will start charging customers a negative interest rate of 0.6%. The measure will apply to customers with deposits worth one million euros or more.

That's quite chunky, especially if you consider that positive interest rates (it still feels a bit weird that we have to clarify this now) haven't been at 0.6% for a while now.

As a reason for imposing the charge, UBS names the "continuing extraordinarily low interest rates in the euro area" combined with "increased liquidity regulations".

It's a direct consequence of steps by the European Central Bank asking private banks to pay a small percentage for storing their money with them instead of lending it out or investing it.

The quality of economic growth needs to be measured, not just the quantity, if the government is to understand exactly how GDP growth affects people up and down the country, economists have proposed.

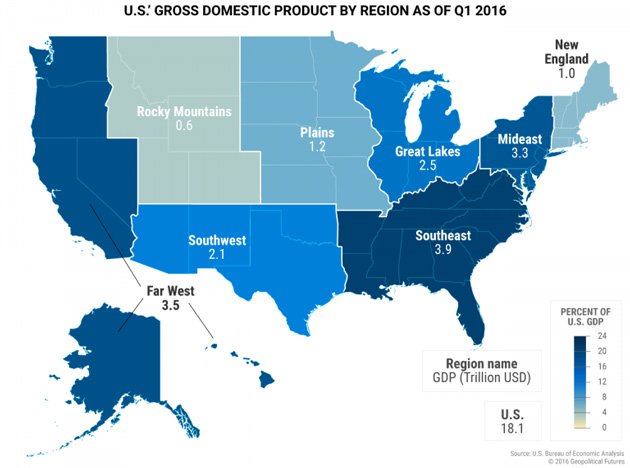

Growth varies across the country with jobs and wages distributed unevenly, so the Inclusive Growth Commission (ICG) and the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce want the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to publish figures on quality of life alongside GDP numbers.

“Traditional metrics of economic performance, such as GDP or at a regional level gross value added (GVA), are a poor guide to social and economic welfare,” said the ICG’s report.

“They also do not tell us anything about how the opportunities and benefits of growth are distributed across different spatial areas and social or income groups. Nor do they do a good job of tracking structural economic change, the sustainability of growth, or the human impact of shifts in the labour market.”

Local productivity, local incomes, the distribution of earnings, pay changes for the lowest paid and levels of regional economic inactivity could all form part of this new inclusive growth metric, said the ICG which is chaired by Stephanie Flanders, JP Morgan’s chief market strategist.

Growth varies across the country with jobs and wages distributed unevenly, so the Inclusive Growth Commission (ICG) and the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce want the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to publish figures on quality of life alongside GDP numbers.

“Traditional metrics of economic performance, such as GDP or at a regional level gross value added (GVA), are a poor guide to social and economic welfare,” said the ICG’s report.

“They also do not tell us anything about how the opportunities and benefits of growth are distributed across different spatial areas and social or income groups. Nor do they do a good job of tracking structural economic change, the sustainability of growth, or the human impact of shifts in the labour market.”

Local productivity, local incomes, the distribution of earnings, pay changes for the lowest paid and levels of regional economic inactivity could all form part of this new inclusive growth metric, said the ICG which is chaired by Stephanie Flanders, JP Morgan’s chief market strategist.

The Commission also includes former Rolls-Royce chief executive Sir John Rose and London School of Economics professor Henry Overman.

The recommendation comes at a time when the ONS is looking for ways to beef up its capabilities.

Other official bodies including the Bank of England are also trying to improve their forecasting models.

One problem linked to the idea of inclusive growth is that the economy has been growing and unemployment has been falling, yet wage growth has remained muted.

Bank of England officials are studying the problem closely, recalibrating their theories of slack in the economy and examining sources of wage growth.

Extra detail from the ONS on inclusive growth could help to shed light on the variance in pay and jobs in different parts of the country and the labour market.

The IGC also recommends the Chancellor merge a series of initiatives including the Local Growth Fund and the Life Chances Investment Fund into one Inclusive Growth Investment Fund, with a combined budget of £3.8bn per year.

As a result it could better coordinate investment to target the proposed new measure of inclusive growth, the IGC suggests.

The recommendation comes at a time when the ONS is looking for ways to beef up its capabilities.

Other official bodies including the Bank of England are also trying to improve their forecasting models.

One problem linked to the idea of inclusive growth is that the economy has been growing and unemployment has been falling, yet wage growth has remained muted.

Bank of England officials are studying the problem closely, recalibrating their theories of slack in the economy and examining sources of wage growth.

Extra detail from the ONS on inclusive growth could help to shed light on the variance in pay and jobs in different parts of the country and the labour market.

The IGC also recommends the Chancellor merge a series of initiatives including the Local Growth Fund and the Life Chances Investment Fund into one Inclusive Growth Investment Fund, with a combined budget of £3.8bn per year.

As a result it could better coordinate investment to target the proposed new measure of inclusive growth, the IGC suggests.