Michael Boyd, author of Industrial Insights: Tariffs, by their nature, create inefficiencies. As a consumer, it pays to be anti-tariff. If China is dumping steel below cost, that means finished products made with that steel within our borders are being sold to consumers below cost. For the United States, that also means we're "exporting" the environmental impact that often inevitably accompanies industrial activity. With wages stagnant for many, tariffs increasing costs on Americans make for an easy political talking point.

While the narrative is that we need to protect our aerospace and defense industries, the section 232 Ruling stated that the U.S. military requirements for steel and aluminum represent only 3% of total U.S. production. It is incredibly small. If this a national security issue, the U.S. government can support production via above-market long-term contracts with quality suppliers or through targeted tariffs or quotas.

Given the support for a blanket tariff, I worry about far-reaching impact. While this is fundamentally about trade, my concerns are on the impact for value-add producers further down the production chain. Aerospace and defense is a massive industry that helps our trade balance: we exported $146 billion in 2016 within this category. It is very easy to see a case where this political stance can cause more harm than good. Even without widely-expected retaliation, higher manufacturing costs by extension means lower demand for exports.

Eric Basmajian, author of EPB Macro Research: Tariffs are a controversial economic policy. Whether they are a good policy or not depends on what ideology and economic beliefs you hold. If the goal is to maximize global economic output, at the expense of job-loss in some countries, then tariffs are a bad policy and free trade would likely result in the greatest total global economic output. If the goal is to revive a certain industry to bring back jobs, tariffs are a necessary policy.

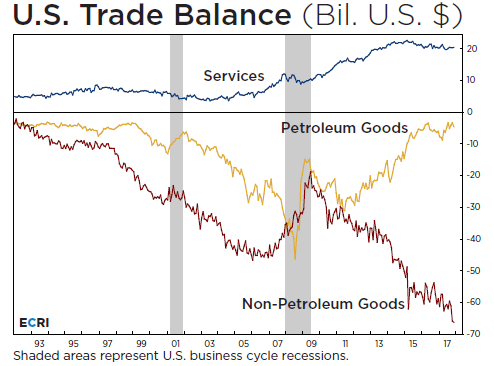

In the United States, there is absolutely a trade problem that needs to be addressed; the non-petroleum trade deficit has reached a record high so President Trump is certainly feeling pressure to act on this campaign promise. I am not sure this exact tariff is the best policy, but it is likely to go through nonetheless.

Non-Petroleum Trade Deficit:

Source: ECRI

The goal of this tariff to target steel industry manipulation by China, specifically the subsidized steel dumping through Canada. Steel and Aluminum only represent 1.5% of US imports and 1-2% of global trade. This specific tariff will not have large impacts. However, the retaliation and escalations of trade wars are what will impact markets.

As a general rule, the country with the largest trade deficit has the upper hand and the leverage in the negotiations. Put another way, Germany's exports as a % of GDP are 46%; South Korea, 42%; Mexico, 38%; Canada, 31%; China, 20%; and the United States, 12%. If all trade stopped tomorrow, the United States is hurt the least in terms of impact to GDP simply due to relative domestic demand. The United States does have the leverage in this negotiation. The specific industry, steel and aluminum are not a large portion of global trade so the market is likely overreacting. As retaliation attempts intensify, more market dislocations are likely.

William Koldus, author of The Contrarian: This is a loaded question. Tariffs are a tax, which is a negative; however, many governments and central banks are involved in providing subsidies and protection to various industries. Tesla (TSLA) is an example, in the United States, of a company that has received and benefited from government largesse. Thus, when is "free trade" really free trade?

Joseph L. Shaefer, author of The Investor's Edge®: Tariffs are not an economic policy. They are a political contrivance, a political convenience, a political negotiating tactic and, sometimes, economic suicide. See Smoot-Hawley 1930. (In fairness, in that case, the US placed tariffs on more than 20 THOUSAND products from abroad.)

Eric Parnell, author of The Universal: I am someone that believes in policies to improve the prospects of domestic manufacturers, having worked as an economist in anti-trust and trade issues in the past. However, I am someone that is strongly against tariffs as a policy to achieve this goal, as they work directly against promoting long-term economic growth and prosperity.

Tariffs are likely to lead to higher input costs not only for those manufacturers that import these inputs but also for those that rely on domestic production, as these prices are likely to rise as well in response to the pricing shift in the marketplace. These higher costs are likely to be passed along at least in part to customers, thus resulting in an indirect tax on businesses and consumers. Moreover, such protectionist trade actions have historically resulted in retaliation in kind by foreign governments, thus further dampening growth and resulting in additional negative pricing effects. While such policies may be well intended, they invariably end up being counterproductive in working to achieve their intended goals.

Kirk Spano, author of Margin of Safety Investing: Well, the short answer is that tariffs generally don't work well and have unintended consequences. History is ripe with those lessons. However, people often feel as if some foreigner has wronged them, so they support these usually counterproductive measures.

Certainly, in rare circumstances, very directed measures can be taken to counter a bad actor, but in those situations, the tariff is a last resort as other measures, such as domestic subsidies or bilateral trade negotiations are usually more productive.

No comments:

Post a Comment